Joel Belz answered the angry phone calls himself.

When 10, then 20, and then 30 and 40 irate readers called the offices of World magazine to complain about a cover story on a Republican presidential candidate—questioning the man’s commitment to conservatism and raising questions about his character, his multiple marriages, and how he’d earned his money—Belz took the calls.

He asked each one the same question.

Could they point to any facts that were wrong?

He understood they didn’t want the Christian newsmagazine to criticize a Republican, and that if the candidate lost and Democrats won the White House, that would be bad for conservatives. But could they point to anything in the article that was actually incorrect? If they could show him an error, he said, he would give them a free year’s subscription.

“So far,” Belz told the Asheville Citizen-Times in 2000, as John McCain’s insurgent campaign started to falter, “not a single subscriber has challenged a phrase of our report.”

Belz always believed that Christians needed the news. In an increasingly liberal and secular society that said everything is relative, he thought conservative evangelicals and orthodox Bible-believers, in particular, needed “sound journalism, grounded in facts and biblical truth.” Even—especially—if it was challenging.

“We wouldn’t pretend there are clear biblical directives on every issue,” Belz said in 2000. “But there are facts that [have] to be stated publicly. In that sense, we believe the Bible calls for the demonstration of truth.”

Belz died at home in Asheville, North Carolina, on February 4. He was 82.

Belz founded It’s God’s World, a Christian newsmagazine for middle school students, in 1981, and expanded the idea to other age groups with Exploring God’s World, Sharing God’s World, God’s Big World, and God’s World Today.

He launched World, for adults, in 1986. The motto of the magazine was taken from Psalm 24: “The earth is the Lord’s and the fullness thereof, the world and those who dwell therein.”

Belz described World as a magazine for “the 5 percent of the people in a typical evangelical church who are serious about applying their faith to the rest of their lives.” The mission, he said, was simply “to help readers see the world and everything in it from a God-centered perspective.”

Belz also helped start the World Journalism Institute in 1999 to cultivate Christian journalists committed to factual reporting. The institute has trained more than 700 people, to date. Some have worked for national media organizations including The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, Los Angeles Times, and USA Today, as well as many state and local papers, politically conservative publications, and religious outlets including Baptist News and Christianity Today.

“He leaves behind decades of service to Christ’s church, a trusted institution, a lengthy body of work, and a new generation of journalists and writers who stand on his shoulders,” the Colson Center said in a statement.

Andrew Walker, a World editor and a theology professor at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, called Belz a “titan of his times” and “a legend of Christian journalism.”

“Evangelicals owe him a tremendous debt of gratitude for the legacy he has left,” Walker said, “one of professionalism, conviction, and excellence.”

Belz was born on August 10, 1941, in Marshalltown, Iowa. His father and mother, Max Victor Belz and Jean Franzenburg Belz, were part of the Bible Presbyterian Church, a conservative Calvinist denomination led by Carl McIntire and others who split from the mainline Presbyterian church during the modernist-fundamentalist controversies. The Belzes helped start a Presbyterian school and plant a church a few miles outside of Walker, Iowa, then a town of about 460 people.

The family had eight kids—raised to read the Bible, sing hymns, recite the Westminster Catechism at breakfast, and love church.

The family also ran a printing operation in their basement. Belz learned to operate the linotype press at age 11 and loved it.

He tried to go into the printing business for himself as a freshman in college, but the enterprise quickly ended in disaster. He borrowed money from his grandfather to buy a linotype and took it with him to Covenant College, a Presbyterian school then located in St. Louis. As Belz attempted to move the printing press into the school basement, there was an accident, and it fell down a flight of stairs.

“It may have been worth thousands at the top of the stairs,” he would later say, “but by the time it reached the bottom it was worth $20 in scrap metal.”

The disaster didn’t dampen Belz’s passion for printing, though. Before he graduated, he spent a semester working on a prototype for a Christian newspaper.

“It was always his ambition,” his sister Julie Lutz told World.

After graduation in 1962, Belz went to work for Covenant College and helped scout out a new location in Lookout Mountain, Georgia. He went back to school to earn an MA in communications and then returned to Covenant to work in public relations and to teach classes in media, English, and logic. He discovered he wasn’t good at teaching, though, and quit after two years.

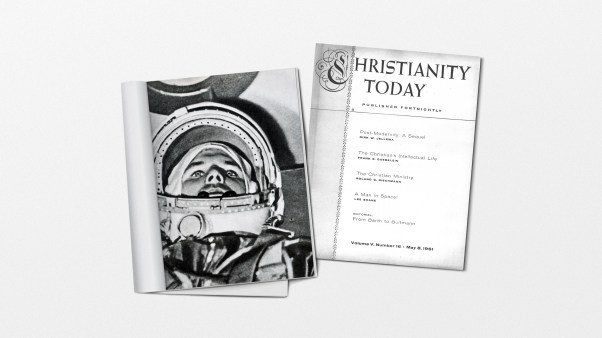

An opportunity to return to publishing arose in 1977 with The Presbyterian Journal in Asheville, North Carolina. Belz took the job. The journal was founded in 1942 by Billy Graham’s father-in-law, L. Nelson Bell (who later went on to found Christianity Today). The journal was supposed to fight theological liberalism in the Presbyterian church, but with the separation of conservatives and the founding of the Presbyterian Church in America, it lost a lot of relevance. By the late ’70s, the journal was in decline and fast losing subscribers.

The Presbyterian Journal was also going through a crisis of leadership.

“The staff became so divided,” former World editor Marvin Olasky recalled, “that writers and editors began working in two separate buildings.”

Belz proposed and launched his first children’s magazine in 1981. It was popular at Christian schools and drew bulk subscriptions. In the next few years, Belz added four more publications for different age groups. Together, the children’s newsmagazines brought in about 250,000 weekly paid subscriptions—more than 10 times the number of subscriptions for The Presbyterian Journal.

The board decided to put Belz in charge, and he proposed an ambitious new project: an alternative Christian newsmagazine for adults.

“Huge gaps existed in the effort to help Christians think biblically,” Belz later explained. “No one was picking up each week’s political news, international happenings, media developments, advances in science, changes in the welfare system, matters of health and medicine—no one was regularly (and rigorously) reflecting on all these aspects of life from a pointedly and conservatively biblical point of view.”

Christianity Today, then a biweekly magazine, focused its news reporting on the church and what evangelicals were doing in the world. World, in contrast, wanted to cover everything—from a uniquely Christian perspective.

World, however, almost failed as fast as Belz’s college printing business. The first issue was put out in March 1986. It was 16 pages, printed on glossy paper, with congressmen Phil Gramm and Warren Rudman in color on the cover. Inside, theologian R. C. Sproul offered analysis of proposed legislation, and there was reporting on the violent political struggle in Nicaragua.

Subscriptions did not flood in.

After 13 issues, the magazine was about $300,000 in debt. It only had about 5,000 readers and many of them didn’t seem too happy with what they were reading.

“Christian adults disagree on a lot more issues than Christian kids,” Belz said.

The board of The Presbyterian Journal decided to cancel the publication. Belz, however, had a counterproposal. He suggested that The Presbyterian Journal should shut down and its resources be invested, instead, in World, which he calculated he could produce at a reduced cost of less than 10 cents per copy.

The board agreed, put $300,000 into the fledgling magazine, and Belz relaunched World in 1987.

“For the next five years,” he later recalled, “the goal was survival. Could we publish one more edition? Could we pay one more week’s postage bills? Could we meet salaries one more time? … After the first five years, we still had fewer than 20,000 subscribers and were hemorrhaging red ink faster than we wanted anybody to know.”

The newsmagazine survived, however, and achieved some stability by the early 1990s. By the time World celebrated its tenth anniversary, more than 85,000 subscribers were receiving the 32-page magazine 50 times per year.

The magazine’s profile was boosted by conservative political leaders, including William Bennett and Newt Gingrich, who praised it publicly. But World really set itself apart by its commitment to news reporting.

“We had a sense that this was a void,” Belz said in 1996.

He criticized the many successful Christian publications that didn’t put any resources into reporting: “It’s kind of scary that people who are supposed to be so committed to the truth and to the Word have so easily accepted a communications model that’s based so much on feelings and experiences. Everything’s about how people feel. It’s getting harder for people to focus on what’s true and what’s false.”

As part of that commitment to focus on facts, World also did investigative work, reporting on the misconduct of Christians and the scandals and cover-ups troubling many evangelical institutions.

Olasky, who joined World in the early 1990s, said it bothered Belz that Christian media organizations hadn’t broken the story of the scandal that brought down televangelists Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker.

“Joel said, ‘Gee, I wish we had done that,’” Olasky said. “We don’t want to leave it to the secular press to expose wrongdoing within the church.”

World went on to report on numerous evangelical scandals, including sexual abuse at a missionary boarding school in West Africa, megachurch pastor Mark Driscoll’s plagiarism and manipulation of bestseller lists, megachurch pastor James MacDonald’s bullying and spiritual abuse, Christian college president Dinesh D’Souza’s apparent marital infidelity, and more.

Any one of World’s near-weekly issues had the potential to set off a bomb in American evangelicalism. It gave the magazine enough of an edge that Christian media commentator Terry Mattingly called it “Rolling Stone for cultural conservative evangelicals.”

If some readers were occasionally angry about the critical coverage of Republicans, that didn’t hurt either, according to Belz. He claimed conservative attacks on World’s reporting on John McCain only “put us on the map.”

And no one ever did get that free year’s subscription.

“As much as Joel’s vision gave everyday vibrancy to timeless truths found in Scripture, he was also the son of a pastor who ran a print shop in the basement,” wrote Belz’s sister-in-law Mindy Belz, who reported for World for 35 years. “He came from small beginnings in rural Iowa, the second-oldest of eight children. And he was a mid-century newspaperman at heart.”

Belz stepped back from the magazine amid health concerns but continued writing columns up to January 2024. One month before his death, he wrote about the dangers of deception.

“Our culture has learned how to play fast and loose with the truth,” Belz told World readers. “And we Christian believers aren’t immune to the infection that saturates the culture we live in.”

Belz is survived by his wife of 49 years, Carol Esther; daughters Jenny Gienapp, Katrina Costello, Alice Tucker, Elizabeth Odegard, and Esther Morrison; their children and grandchildren; and a large extended family.

His funeral will be held at Arden Presbyterian Church near Asheville and streamed online on Saturday, February 10. He will be buried in Black Mountain, North Carolina, in a coffin built by family members.