Joining 80 leaders from 24 countries in Washington, DC, last September, the World Evangelical Alliance (WEA) announced 2020 to be the Global Year of the Bible.

“Ignorance of Scripture is ignorance of Christ,” said WEA general secretary Ephraim Tendero. “In contrast to the sacred writings of many other traditions, the Bible is meant to be read and understood by all people.”

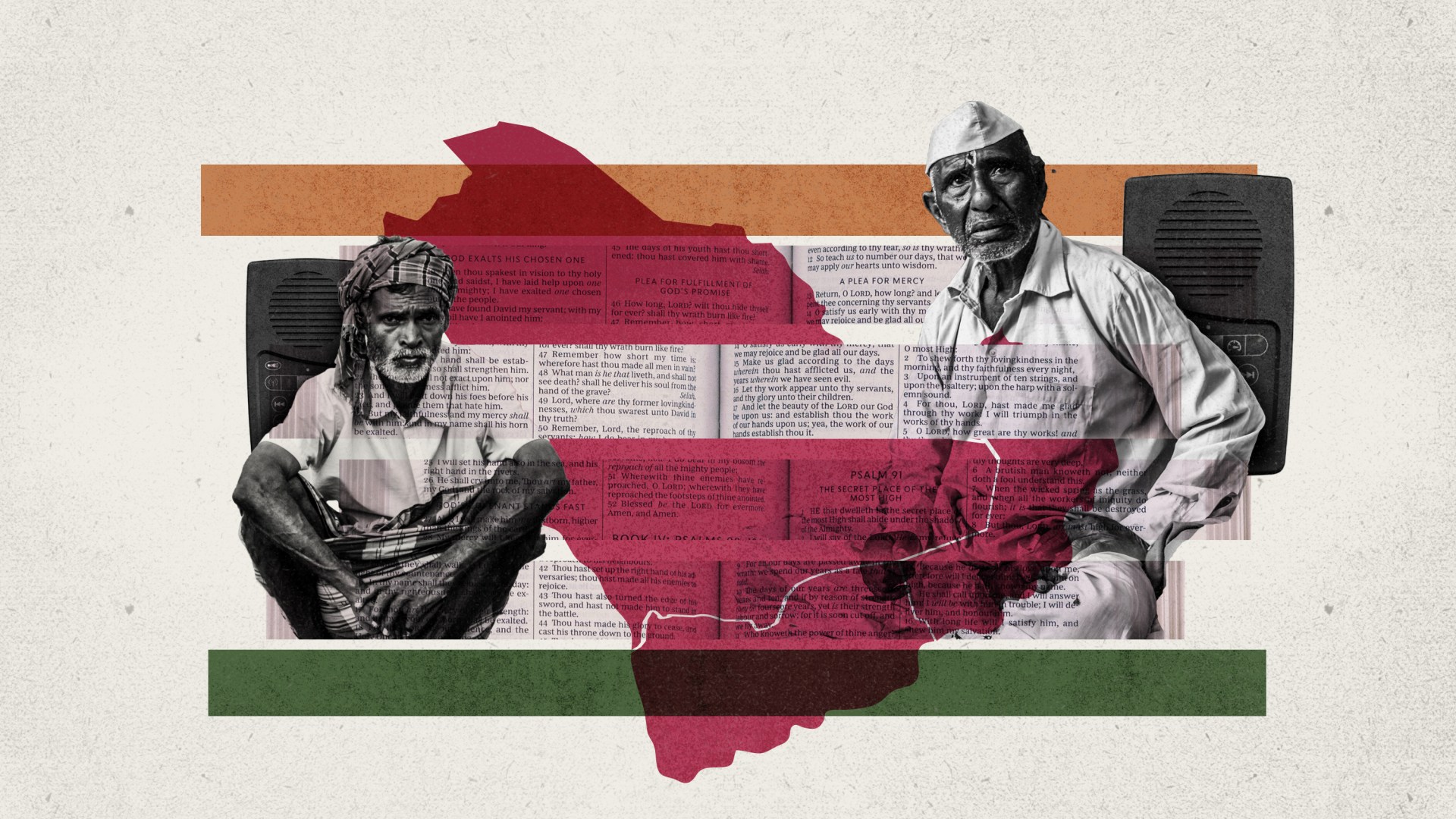

But what if they cannot read? This is the case for up to 40 percent of the 1.5 million Telugu-speaking workers in the Gulf states. Having dropped out of school in their native India, these migrants find that the crowded labor camps of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Bahrain offer the best opportunity to support their families back home.

But having come to the glitzy Gulf to gain a meager share of petrodollars, many find also the spoken—and storied—words of Jesus.

In 2019, the Bible Society of the Gulf (BSG) was awarded “Best Mission Project” by the United Bible Societies (UBS). Honored in the category of “Focusing on Audiences,” BSG’s pioneering audio and storytelling work among illiterates distinguished it among the 159 UBS branches worldwide.

“We help migrant workers rediscover themselves as children of God,” said Hrayr Jebejian, BSG general secretary. “Through the faith and hope of scripture, they gain the strength to navigate their many challenges.”

Jebejian’s book, Bible Engagement, noted during the UBS ceremony, described the long working hours, high rates of suicide, and sexual abuse endured by migrants in the UAE—65 percent of whom are Telugu. Their average monthly wage is $175, which sometimes goes unpaid. The kafala system of sponsorship places the migrant’s passport in the hands of the employer, complicating any return back home.

International attention in recent years has led to legal reform, but the isolation of labor camps means many violations go unnoticed. And the lack of communal space ensures that the church is often the only venue for outside social interaction, whether the migrant is Christian, Muslim, or from the majority Hindu population.

Babu Ganta, communications director for the BSG, first traveled to the Gulf in 1983 to train English teachers. An educated Telugu Indian, his dismay at the average of two suicides per week drove him to write Hope, a simple booklet of scriptural encouragement and the plan of salvation.

“My words won’t comfort, or convict people of sin,” he said, “but God’s words will.”

Yet despite distribution of 300,000 copies in 19 languages, too many were still unreached.

Back in 2000, UBS realized that a changing world demanded it shift from traditional distribution targets to a focus of engagement and transformation.

In South Africa, the local Bible society tackled the AIDS epidemic. The UK society emphasized the arts. The Peru society addressed issues of spousal and child abuse.

In the Gulf, the BSG turned to illiteracy, designing a large print workbook on the Sermon on the Mount as an elementary primer. Over 12,000 have been distributed through migrant churches so far.

“Every night after work, we gather in our room and have a ‘family’ prayer by reading this book,” Renuka, an elementary-educated Telugu working for a cleaning company, told Ganta.

“We share our thoughts and pray for one another.”

But in the late 2000s, the BSG introduced the Mega Voice Player (MVP) and Proclaimer audio tools for those who could not read at all. Loaded with the Telugu Bible and other Christian materials, up to 200 MVPs and 800 Proclaimers are distributed each year. (Proclaimers can be used in a church service of up to 100 people. MVPs are designed for smaller groups.)

“I can’t read my print Bible,” Navin, who works in Dubai, told Ganta. “But my faith returned now that I can hear God speak to me directly in my own language.”

And Prasad, a convert from Hinduism, took an MVP back to his home village in India’s Krishna district. Eventually, he planted its first church.

“These people are missionaries in waiting,” said Ganta. “They came to the Gulf for money, but go back with something more precious than gold.”

Yet despite its increased reach, audio technology is still limited by funding and manpower. And Jesus film DVDs and New Testament CDs have grown obsolete.

So in 2011, Ganta discovered oral storytelling, and has been training in it ever since.

In 2018, the BSG equipped 397 church leaders in the method and enabled them to train others. Over 4,300 can now tell stories themselves, and together they reached a combined audience of over 11,000.

“Migrants are tired after working all day, and if you tell them a sermon they will fall asleep,” Ganta said. “But Jesus taught nothing without using a parable—they are easy to tell and easy to repeat.

“We are simply going back to Jesus’ method.”

One Telugu pastor in Bahrain told Ganta how members of his congregation took the stories back to the labor camps, and entertained others. The laborers wanted more, and started coming to church.

Eventually, the congregation doubled in size.

Ganta emphasizes there is no magic formula. Now 70 years old, he consistently encourages the churches to arrange transportation, to prepare meals, and to visit migrants in the hospital. And by ministering in the labor camps, the love of God infuses them with a sense of community.

Jebejian’s book measured the impact.

“Migrants experienced a deeper understanding of the theology of the cross, which allows them to treat personal and corporate suffering as a Good Friday experience that is a prelude to the Easter Sunday experience,” he wrote.

“For them, God is a miracle maker [who] takes care of them.”

The Global Year of the Bible pledges to be a relational network at the grassroots level. The vision was announced at the state-of-the-art Museum of the Bible in Washington, DC, able to rival the UAE in architectural grandeur.

For those with smartphones, the BSG is partnering with the Scottish Bible Society to provide a multi-lingual Bible2020 app for daily reading in over 1,200 languages.

Around the world, everyone can read—or listen—together.

The scriptures, Tendero emphasized, have always ministered to high and low.

“The Bible’s story—infused with the power of Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit—is the foundation for the recognition of the dignity of every individual,” he said in his address.

“[It] undergirds every noble effort to address suffering in the world.”