The global Christian community is buzzing with excitement about the arrival of Chinese Christians eager to serve on many mission fields around the world. While the Chinese church is still developing its capacity as a sending church, this new phase in world missions holds great promise for China and the world—providing a moving demonstration of the maturity of the church in China. Throughout the centuries, many different global mission agencies and missionary workers have contributed to the growth of the mainland Chinese church. The endeavors of Western missionaries like Matteo Ricci, Gladys Aylward, Jonathan Goforth, and Timothy Richard have been well documented in biographies and sermon illustrations. Even today, mentions of Hudson Taylor and his China Inland Mission (CIM) continue to inspire Christian men and women to leave home to share the gospel overseas.

While many expatriates contributed to the present moment in Chinese mission sending, this missionary vision of the Chinese church owes as much if not more to the host of Chinese men and women over the last two centuries who have rooted the gospel message within the Chinese soul. These saints who played such an essential role in the establishment of an explicitly Chinese church deserve to be recognized for their service. May their stories inspire new generations of women and men in China and beyond to serve God wherever he may lead.

1. Ding Limei (1871–1936) A determined evangelist

Evangelist Ding Limei was born into one of the first Christian homes in the province of Shandong. At the age of 13, Ding left home for Dengzhou, (modern Penglai) and enrolled in Tengchow College, which had been founded by the American Presbyterian Mission, North. After graduating, he worked for a few years before returning to study theology for two years at the same school.

Ding was ordained as a pastor in 1898. During the Boxer Uprising in 1900, he was persecuted for his faith and thrown into prison for 40 days where he suffered almost 200 blows by the rod leaving terrible lesions on his skin. After his release, he accepted a position as a Presbyterian minister, resolving to preach the gospel in every province in China, to establish an indigenous Chinese church, and to save the souls of millions of his countrymen. Over the next 20 years he was an active itinerant evangelist, speaking at revivals across the country and leading many Chinese men and women to put their faith in Christ. At the end of his life, Ding focused on theological education, teaching in the North China Theological Seminary and pastoring several congregations. Illness in his later years prevented him from engaging in front line evangelism, but he persisted in praying for the salvation of thousands of countrymen by name, never wavering in his desire to see the people of China won for Christ.

2. Jeanette Li (1899–1968) Cross-cultural evangelist

Jeannette Li was born in 1899 into a Buddhist household. A childhood illness compelled her family to bring her to a missionary hospital and her subsequent recovery led her to enroll in the mission’s school. Li was baptized as the first Christian in her family at age 10. At the age of 16, Lee entered an unhappy marriage with a non-believer. After several years her husband married another woman, leaving Li to raise her son as a single mother.

While caring for her son and her ill mother, Li persisted in her studies and eventually found employment teaching in a government school—an intentional decision she undertook in pursuit of evangelistic opportunities outside the Christian mission school community. Realizing that her true calling was evangelism, she resigned from the school in 1930 and enrolled at the Ginling Bible College in Nanjing to train for ministry. In 1934 she made the first of many trips to Manchuria where she was part of a fruitful cross-cultural outreach in streets, homes, hospitals, and orphanages throughout the region. Her ministry during these years was subject to near constant persecution and harassment from Japanese occupiers. In 1952 Li was imprisoned for 17 months by Communist officials for her faith. Upon her release, Li moved to Guangzhou where she once again volunteered as an evangelist until she was allowed passage to Hong Kong and, eventually, the United States. Throughout all the difficulties in her life, Li continued to share her faith, witnessing to God’s steady provision in times of trouble.

3. Liang Fa (1789–1855) China’s first Protestant Christian

Liang Fa embodies the indigenization of Chinese Christianity—a process that proceeded with fits and starts, periods of foreign patronage, internal persecution, and tension between Christian and Chinese identities. In his early life, Liang grew up in a village where he participated in local folk religious life. As a young adult, Liang worked as a printer assisting the recently arrived Robert Morrison of the London Missionary Society. His subsequent conversion led to the baptism of many family members and a job as the first ordained Chinese evangelist. By midlife, Liang was participating in most of the institutions of the early Protestant missionary movement (the missionary press, local fellowships, schools, a hospital, etc.) and penned one of the most influential Chinese gospel tracts of the 19th century.

Liang showed a tendency towards iconoclasm and embraced a form of Christianity that was strident in rejecting idolatry. Because of his faith and ministry, Liang’s family life became more complicated as he aged, demonstrating several layers of the kinds of conflicts that accompanied becoming a Christian: the real risk in professing faith in Christ, the challenge of participating in religious or ritual life, and tensions over the next generation. Liang Fa is often described as the first fruit or the seed of the indigenous Chinese church.

4. Shi Meiyu (Mary Stone, 1873–1954) Accomplished missionary doctor

One of the earliest second-generation Christians on the continent, Shi Meiyu was born to a Methodist pastor and a mission school principal. As a child, Shi studied both the Chinese classics and Christian literature before heading to the University of Michigan to study medicine.

One of the first two Chinese women to receive a medical degree from an American university, Shi returned to China in 1896 to serve as a medical missionary with the Women’s Foreign Missionary Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church. She spent her remaining decades establishing and running multiple hospitals and participating in a wide range of evangelistic work. Shi served on the China Continuation Committee after the Edinburgh World Missionary Conference of 1910, was the first president of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union in China, and was one of the organizers of the Bethel Worldwide Evangelistic Band. In 1918 she cofounded the Chinese Missionary Society in order to support and send Chinese Christians to evangelize other Chinese people.

5. Shu Shan (?–1900) A courageous Boxer Martyr

Shu Shan and her family were Christians living on the outskirts of Beijing when the Boxer turmoil erupted in the summer of 1900. A grassroots uprising with complicated causes, the Boxer participants called on the spiritual assistance of traditional Chinese mythical heroes to destroy all foreign influences and restore prosperity and security to the common people of North China. Shu’s husband was a local evangelist in charge of his own mission station just outside Beijing. As news of the coming Boxer violence spread, he fled to the mountains in search of safety, sending his wife and their three children under the age of 10 to live with nearby relatives. As the Boxers closed in on their village, Shu and her children were gradually turned away from all possible places of refuge by friends and family alike, eventually returning to their home to wait for death. Shu and her children were seized by the Boxers because of their Christian faith and then tormented, murdered, and cast into a shallow grave near the ruins of their home. The blood of Shu Shan and the many other Christian martyrs of 1900 inspired a generation of expatriate missionaries and local disciples to take up their crosses and follow Jesus wherever he led—their obedience forming the foundation of today’s Chinese church.

6. Sung Shangjie (John Sung, 1901–1944) China’s John the Baptist

Song was born in Fujian province in 1901, the fourth son of a Methodist pastor. Eager to follow in his father’s footsteps, Song graduated from the local mission school and headed to the United States to study theology. Once there, however, he studied chemistry instead, eventually earning his PhD from Ohio State University in 1926. Shortly afterwards, he repented of his selfishness and endeavored to honor his original call by enrolling at Union Theological Seminary in New York. In 1927 Song reported having a dramatic “conversion experience” that compelled him to criticize the liberal theology of his professors. This was a troubled time for Song, resulting in a mental breakdown that saw him placed in an insane asylum. An American pastor intervened, and Song was allowed to return to China where he juggled teaching chemistry and Bible during the week with running evangelistic campaigns on the weekends. In 1931 Song accepted the invitation of Shi Meiyu (see above) and left all his other work to join the Bethel Worldwide Evangelistic Band. Sung was soon known throughout Asia as a fiery preacher whose dramatic behavior on stage and moving songs spoke directly to people’s hearts. For the next eight years, his message of judgment, repentance, and healing brought many people in China and throughout the Chinese diaspora to faith in Jesus. The persistent health problems that he claimed kept him humble eventually took his life in 1944.

7. Wang Laiquan (1835–1901) Hudson Taylor’s brother in ministry

A painter and interior decorator, Wang was baptized into missionary Hudson Taylor’s congregation in Ningbo in 1859. Wang agreed to help Taylor with his struggling hospital, working with the understanding that he would receive no salary but only “a share of whatever the Lord provided.” Wang joined Taylor when he returned to England in 1860 for medical reasons where he helped care for the Taylor children and assisted with the translation of the New Testament into the Ningbo dialect.

After returning to China, Wang began pastoring independent local churches on his own. With no salary from the CIM, Wang used his own money to open a country chapel and supervised a growing number of itinerant local evangelists, eventually becoming a superintendent pastor of a network of self-supported, self-governing churches in the Hangzhou area. Wang cooperated well with CIM expatriate missionaries and on at least one occasion sent money from his churches to support the work of CIM expatriate missionaries.

8. Wu Baoying (1897–1930) Medical missionary to western China

Born in in 1897 to a Christian family in the western China province of Gansu, Wu was one of the first Chinese medical missionaries in China, personally trained by second generation CIM missionary George King at the Borden Memorial Hospital in Lanzhou. Wu and his wife proved indispensable in the running of the hospital following the recall of all the expatriate missionaries from western China after the anti-Christian and anti-foreign violence of the 1927 Nanjing Incident. Wu and his brother also established a mission hospital in their hometown, where Wu was killed by Hui minority rebels during an ethnic uprising in 1928. His final words, as he died at the age of 33, were “The Lord is with us.”

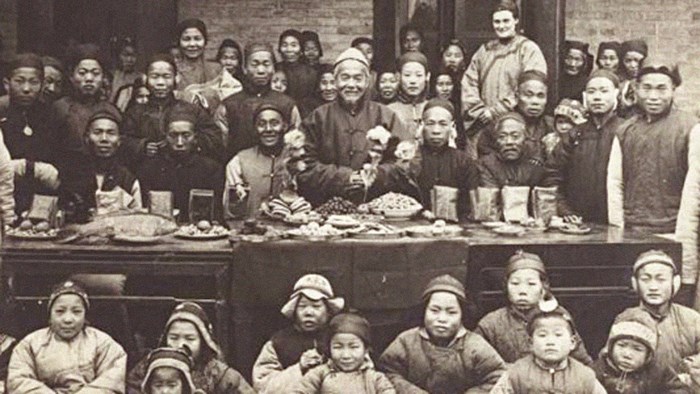

9. Xi Shengmo (Pastor Hsi, 1835–1896) The Overcomer of Demons

The Confucian scholar Xi Zizhi became a Christian following a failed attempt to pass the provincial level exams in Taiyuan, Shanxi. As he exited the examination hall, he received several gospel tracts as well as a list of essay questions on general moral and religious topics devised by British missionaries Timothy Richard and David Hill as a means of opening gospel discussions with Chinese elites. Xi submitted several winning entries in the essay competition, and when he visited the missionaries to collect his monetary prize, Xi was asked by Hill to serve as his secretary and Chinese language tutor. Xi accepted and his new foreign friend soon helped him overcome his opium smoking habit.

Xi became a Christian, changed his name to Xi Shengmo (“Xi, the overcomer of demons”), and returned to his hometown to convert his traditional Chinese medical dispensary into a church and opium refuge for others seeking to overcome their addictions. He was the first indigenous pastor in Shanxi province, immortalized in Geraldine Taylor’s biography, Pastor Hsi: Confucian Scholar and Christian. Xi was fiery, and while he did at times get into conflict with foreign missionaries, a long string of CIM missionaries (including many of the famous Cambridge Seven) served effectively under his direction. His opium refuge played an important role in the early development of the indigenous Protestant church in Shanxi.

10. Yu Cidu (Dora Yu, 1873–1931) An independent revival preacher

Born a preacher’s daughter in the Hangzhou American Presbyterian Mission compound, Yu Cidu was trained as a medical worker. In 1897 she briefly joined an early cross-cultural mission outreach to Korea. In 1904 Yu gave up medicine for full-time ministry and began preaching at revivals across the country. Yu was one of the earliest preachers to cut financial support from the West, seeking to build up the indigenous Chinese church and completely “live by faith.” She later founded the Bible Study and Prayer House, (later the Jiangwan Bible School) in Shanghai, as well as a series of winter and summer Bible study classes, and trained many qualified preachers for the Chinese church. Many of those who became Christians through Yu’s evangelism efforts played important roles in the early 20th century Chinese church revival movement. After hearing her preach at a revival meeting in Fuzhou, Watchman Nee converted to Christianity and dedicated himself to serving God. In 1927 Yu was invited to be the main speaker at the Keswick Convention, the famous annual gathering of evangelical believers committed to spiritual holiness, unity, and global mission, where she implored Western Christians to stop sending missionaries with liberal theology to China.

Andrew T. Kaiser, PhD, has been living and working with his family in China since 1997. In addition to his various online contributions, Andrew is also the author of Voices from the Past: Historical Reflections on Christian Missions in China and The Rushing on of the Purposes of God: Christian Missions in Shanxi since 1876.

G. Wright Doyle is director of Global China Center, editor of the Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity, editor of Builders of The Chinese Church: Pioneer Protestant Missionaries and Chinese Church Leaders, editor and translator of Wise Man from the East: Lit-sen Chang, and co-editor of the series Studies in Chinese Christianity.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month