The world’s largest democracy underwent a significant political shift in its 2024 general election, as Indian voters upended the previously unshakable dominance of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

The BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) remains the largest coalition and will form the next federal government, likely making Modi the first Indian head of state to serve three terms since Jawaharlal Nehru led the subcontinent’s initial post-independence government. But as the official vote counting stretched past midnight on June 4, results indicated that voters rejected Modi’s aspirations for an overwhelming majority that many feared would have empowered him to reshape India’s secular and democratic foundations.

Christians and other religious minorities in India rallied for the cause of pluralism.

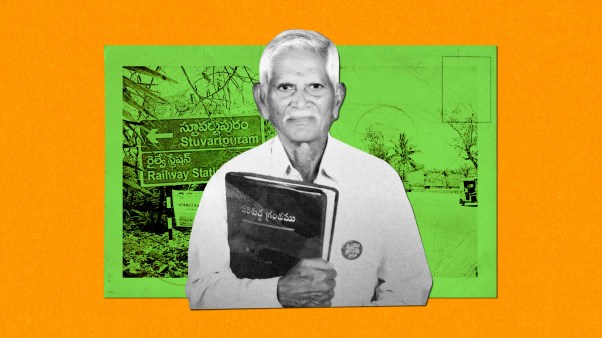

“The people have spoken clearly for a return to the founding ideals of India,” said Vijayesh Lal, general secretary of the Evangelical Fellowship of India (EFI), which represents more than 65,000 Protestant churches. “They prefer harmony over narrow sectarianism and divisive politics.”

Running a populist campaign of Hindu nationalism, in 2014, Modi led the BJP to a landslide victory, securing 282 of 543 seats in the Lok Sabha, India’s lower house of parliament—the first outright majority for a single party in 30 years. His mandate was strengthened in 2019 when the BJP increased its tally to 303 seats.

Having won political control over the federal legislature and many of India’s 28 states, Modi seemed invincible heading into 2024. Many critics worried that the nation’s multiparty democracy was sliding toward authoritarianism.

Instead, opposition leaders now claim the results of the 2024 election “shattered Modi’s aura of invincibility.” While the BJP-led coalition still secured a slim parliamentary majority with 286 seats, the BJP itself won only 240 seats—63 fewer than in 2019 and well short of the 272 seats it needed in order to govern alone.

Modi had publicly stated that he would win 370 seats and that his coalition would win over 400. In such a scenario, Christians and many other Indians suspected Modi would move the nation closer to the vision of the far-right Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the ideological parent of the BJP.

John Dayal, spokesperson for the All India Catholic Union, said an overwhelming mandate could have empowered Modi to reshape India into a Hindu nation, disenfranchising religious minorities and indigenous communities from their rights and resources.

Founded in 1925, the RSS is considered one of the largest far-right volunteer movements in the world. One of its founding leaders, M. S. Golwalkar, wrote that India’s religious minorities must be “wholly subordinate to the Hindu nation, claiming nothing, deserving no privileges, far less any preferential treatment, not even citizen’s rights.”

Such rhetoric has become embedded in the BJP narrative, resulting in an increase of hate crimes against Christians. However, data from the Pew Research Center indicates that the party’s polarizing brand of nationalism has fewer takers in large swaths of India, especially in the south. The backlash among traditionally tolerant Hindus, combined with frustration over rural distress, inflation, and unemployment, has now led to a more fragmented political scene.

Many Indian Christians see this as a blessing.

“The result is like breathing fresh air after a long time of suffocation,” said C. B. Samuel, former head of EFI’s disaster relief and development commission.

Despite the setback, Modi still called the result the “victory of the world’s biggest democracy,” as he announced his intention to form the next government in negotiation with coalition allies. This development, sources told CT, signals a return to a more pluralistic democratic reality.

Samuel interpreted the opposition surge as a movement to support marginalized communities, to avoid favoritism of any religion, and to promote a sense of hope.

A. C. Michael, coordinator of the United Christian Forum, a human rights group that tracks data on Christian persecution, predicted a coalition government will “put Modi on a leash” and ensure greater accountability.

The BJP’s main challenger was the newly formed Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA), a broad coalition of regional and ideological rivals of the BJP brought together by Rahul Gandhi of the Indian National Congress party.

Gandhi, the great grandson of Nehru and heir to India’s preeminent political dynasty, embarked on a grassroots campaign of unprecedented scale—including two marches of 2,000 miles and 4,200 miles across India over two years. Alongside allies such as the Samajwadi Party and Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, Gandhi highlighted issues including Modi’s Hindu nationalism, alleged cronyism, and the erosion of civil liberties during his terms in office.

An aggressive social media offensive helped the INDIA coalition challenge the perception of Modi’s inevitable success. And in heartland states such as Uttar Pradesh—India’s most populous, with 241 million people—significant discontent was evident within the party’s traditional support base as the BJP lost roughly half its seats.

“The BJP grew increasingly authoritarian and instilled a climate of fear,” said an attorney in Uttar Pradesh, granted anonymity due to his close work with the persecuted church. “This verdict should alleviate those concerns.”

But persecution is prevalent in other states as well, stated award-winning human rights and peace activist Cedric Prakash, a Gujarat-based Jesuit priest. He called the Modi government “particularly hostile” to all religious minorities but noted that other adversely affected communities included small farmers, indigenous coastal people, migrant workers, casual laborers, tribals, Dalits, and other vulnerable sections of society.

Civil society groups rallied on behalf of such communities to swell the opposition’s ranks, and Prakash said Christians should join them to pursue the “gospel values” of justice, liberty, and equality.

Alongside their vote, Indian Christians also mobilized in prayer. EFI members, which represent more than 50 denominations and 150 ministries, as well as other denominations came together in marathon prayer sessions and interchurch prayer chains.

“People cried out to God, humbling themselves, to ‘heal their land’ and reaffirm democracy and freedom during the elections,” said Paul Dhinakaran, chancellor of Karunya University and chairman of Jesus Calls Ministry.

Across the nation, hundreds of such groups, including Dhinakaran’s National Prayer and Ministry Alliance, fervently sought divine intervention as the tense vote counting unfolded—underscoring the significance of the electoral outcome for India’s religious minorities.

“Many shed tears of joy,” said Samuel. “Now is the time for gratitude, to step back to see God at work.”

Yet Prakash said while this “second-best” election scenario was still an answer to prayer, it was now up to Modi’s coalition partners to ensure the new government does not tamper with the constitution.

“India has proved to the world that democracy, social justice, and constitutional laws must prevail over all other considerations,” said Dhinakaran.

The INDIA coalition will also have to work hard to become a functional opposition, as the diverse alliance united to defeat Modi without a shared ideological vision. While Gandhi’s Congress Party is the largest in the coalition, more than half of INDIA’s seats came from regional parties.

Yet the outcome still inspired hope among Christians.

“Indeed, we were expecting this kind of result,” said Jacob Ninan, pastor of Trinity Highland Tabernacle Church in the southeast state of Kerala, where Christians comprise 18 percent of the population. “There was intercession throughout the nation for a restoration to democracy.”

Nonetheless, for the first time, the BJP was able to secure one of Kerala’s 20 parliamentary seats after years of failing. Paradoxically, this came through direct appeals to Christians through local churches, notwithstanding the party’s rhetoric elsewhere in India. (The Congress Party still claimed majority support of local citizens, securing 14 seats.)

Ninan attributed the BJP’s new seat in Kerala to its local candidate’s charisma, citing his fame as an actor, his assistance to the poor, and his neutral stance on religion as he avoided the Hindutva line.

Prakash was more concerned in his analysis. “Voting for the BJP in Kerala is a troubling signal for secular democracy,” he said. “If Christians voted for the BJP, they would soon learn it is an anti-Christian party.”

Despite the positive turn in election results overall, however, Lal warned that social polarization and Christian persecution in India are unlikely to disappear immediately. Decades are needed, he said, to form the societal will necessary to reject sectarian hate and to restore fraternity. The outlook, in fact, “remains grim,” he said.

Nonetheless, the current political balm is welcome.

“The 2024 Indian elections defied expectations,” Lal said. “The BJP’s hollow victory and the opposition’s triumphant loss reaffirmed democracy’s power to change the course of a nation, against all odds.”