I pastor an American Baptist church in a small town in rural Illinois. When the current building was dedicated in 1968, there were more than 300 members. By the last 1990s, there were about a hundred. When I became the pastor in 2006, just 50. Now, on a good Sunday I can look out from the pulpit and see 20 souls in the seats.

Where did they all go? I became a social scientist, in part, to try to figure that out. In my forthcoming book, The Nones: Where They Came From, Who They Are, And Where They Are Going, I document in detail how and why so many Americans are now counted among the ranks of religiously unaffiliated in the United States.

What I discovered was that while many people have walked away from a religious affiliation, they haven’t left all aspects of religion and spirituality behind. So, while growing numbers of Americans may not readily identify as Christian any longer, they still show up to a worship service a few times a year or maintain their belief in God.

The reality is that many of the nones are really “somes.”

Nones by Belonging

Religious disaffiliation is at an all-time high—claimed by nearly a quarter of the population—when measured through surveys on religious belonging. The General Social Survey, for example, asks a common version of the question: “What is your religious preference?” Respondents can choose from a long list of options, including “no religion.”

In 1972, just 1 in 20 Americans had no religious affiliation. That share inched up only marginally for the next two decades, before beginning its climb in the 1990s. The unaffiliated jumped about 4 percentage points between 1993 and 1996, up to nearly 1 in 6 (nearly 15%) by the new millennium.

The number of respondents indicating they had “no religion” continued to grow, reaching 1 in 5 in 2012 (19.6%) and close to 1 in 4 (23.7%) in the most recent wave of the survey available.

There’s ample evidence emerging that the GSS undercounts the share of Americans who have no religious belonging because some survey respondents may be more reluctant to indicate to a live interviewer that they are religiously unaffiliated. Still, all surveys agree on this point—those without a religious tradition are growing every year, the so-called rise of the nones.

In my book, I note how the only other religious tradition to change in size in a significant way are mainline Protestants (such as United Methodists and Episcopalians). The data indicates that many nones are people who were raised in one of these traditions, but walked away from it as adults.

Nones by Behavior

While belonging is the most popular way to measure religiosity, there are other dimensions of religious life. If we believe “actions speak louder than words,” we may look to whether religious behavior has shifted as dramatically.

A good place to look is church attendance. Social science knows that communal worship gatherings are crucial for generating social capital, providing theological education, and encouraging the faithful to remain devoted to the tenets of their faith tradition.

Like religious affiliation, religious attendance in the US has been declining since the 1970s, but incrementally.

In the 1970s, about 3 in 10 Americans indicated that they attended worship services at least once a week. At the other end of the spectrum, about 2 in 10 said that they never or rarely attended church services. The percentage of Americans who fell into this lowest category of church attendance stayed stable through the 1980s then incrementally increased from that point forward. By the 2010s, nearly a third of all Americans said that they never attended church or attended less than once a year.

At the same time, the share of Americans who were weekly attenders has decreased slowly. Between the 1990s and the 2010s, the share in this top category dropped about 2.5 percentage points. Currently, about a quarter attend weekly or more, and two-thirds attend a worship service at least once a year.

What is driving this drop in attendance? For decades, social scientists believed that young people would drift away from religion in early adulthood, but then come back to church when they got married, had children, and settled down. That was true for Baby Boomers, but now the data indicates that among younger age cohorts, that’s not occurring as much. More young people stop attending church in their 20s and never return.

Nones by Belief

The final dimension of religiosity is religious belief. These questions are notoriously difficult to ask on surveys, but the GSS began to explore the topic in 1988.

Respondents can select among six options to the question “Which statement comes the closest to expressing what you believe about God?” They range from “I know God really exists and I have no doubts about it,” to an atheist option, “I don’t believe in God,” and one that would describe an agnostic belief, “I don’t know whether there is a God, and I don’t believe there is any way to find out.” It’s reasonable to assume that those who chose either the atheist or agnostic options would be counted as a “none” when it comes to religious belief.

In 1988, just 5.1 percent of Americans chose the atheist or agnostic option on the survey. Twenty years later, that had increased to 8 percent, with 3 percent choosing the atheist option. From that point forward, the share who held to these beliefs has drifted up to about 11 percent in the last two waves of the survey.

Combining the Three Bs

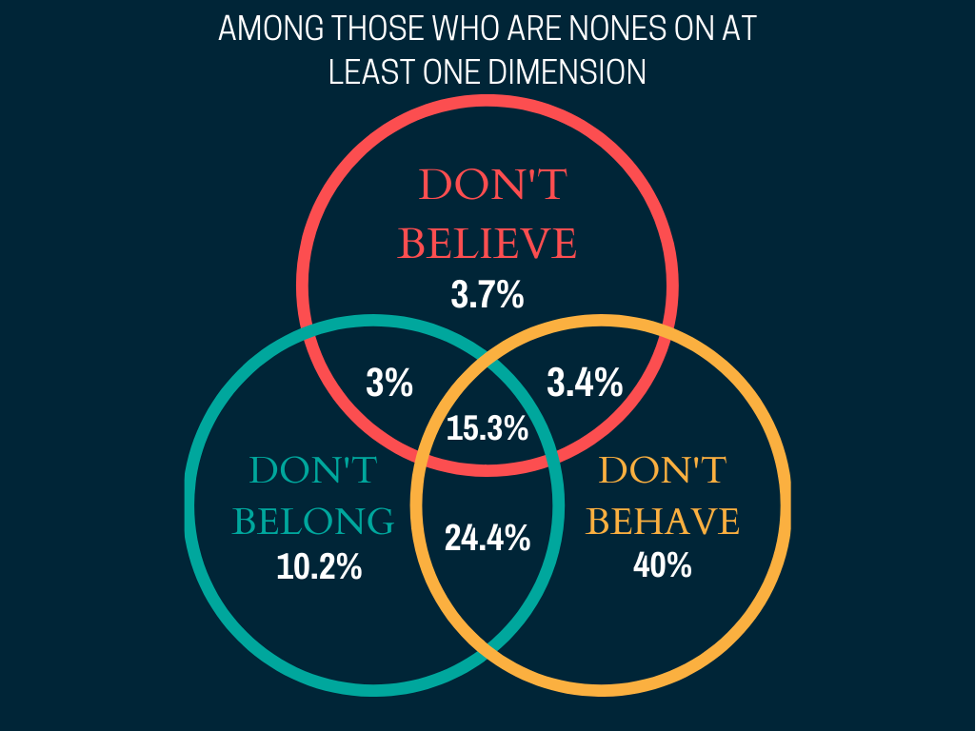

A majority of Americans across faiths (60%) can’t be classified as a none by any measure—belonging, behavior, or belief. But among 40 percent who have disaffiliated in at least one of the three, few can be categorized as nones across the board.

The Venn diagram illustrates how the remaining 40 percent of the population is situated around these three dimensions of religion. Note that behavior—not attending church—is the most common reason why someone would fall into the notes.

Forty percent of the nones overall don’t attend church but still identify with a religious affiliation and believe in God at some level. Another quarter of the nones neither go to church nor indicate an affiliation with any religious group (the intersection of the green and yellow circles), but still have a belief in God. Those two groups represent two-thirds of the nones.

No wonder research has shown that the unaffiliated in America are just as likely to return to church and reclaim a Christian identity as they are to become self-identified atheists and agnostics. In my book I write that nearly 20 percent of people who identified as “nothing in particular” had changed their affiliation to Christian just four years later. And this “nothing in particular” category represents nearly 1 in 5 Americans. The harvest is plentiful!

For the remaining two factors, it’s clear that belonging is the next to fall by the wayside, followed by religious belief. Only a quarter of all nones indicate an atheist or agnostic view of God (all those represented by the red circle).

The center of the Venn diagram indicates that just 15.3 percent of the population that are nones on one dimension are nones on all dimensions. That amounts to just about 6 percent of the general public who don’t belong to a religious tradition and don’t attend church and hold to an atheist or agnostic worldview.

As Ed Stetzer wrote last year, “It would be a mistake to dismiss 25 percent of the population as unreachable or act as though they were all atheists. It would also be a mistake to think church as usual will appeal to the nones.”

He told church leaders: “The unaffiliated aren’t the unreachable.” But for leaders to engage this growing segment of the population, in their communities and hopefully in their churches, they must get an accurate picture of the range of religious unaffiliation in the US.

Understanding the composition and trajectory of this group is crucial, but it’s incredibly easy to overgeneralize about a group based on what it is not rather than what it holds in common. I wish I could give churches a simple checklist of things pastors can do to bring the nones back into their congregations, but there are at least 60 million adult nones in the United States and 60 million reasons why they left organized religion.

Trying to understand this group from a sociological perspective is a good start, but Christians need to be willing to listen to the nones themselves. Conversing with the nones—in a non-judgmental way that seeks to understand their concerns and baggage—is the best approach that the church can take to address this significant shift in the American religious landscape.

Ryan P. Burge is an assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University. His research appears on the site Religion in Public, and he tweets at @ryanburge.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month