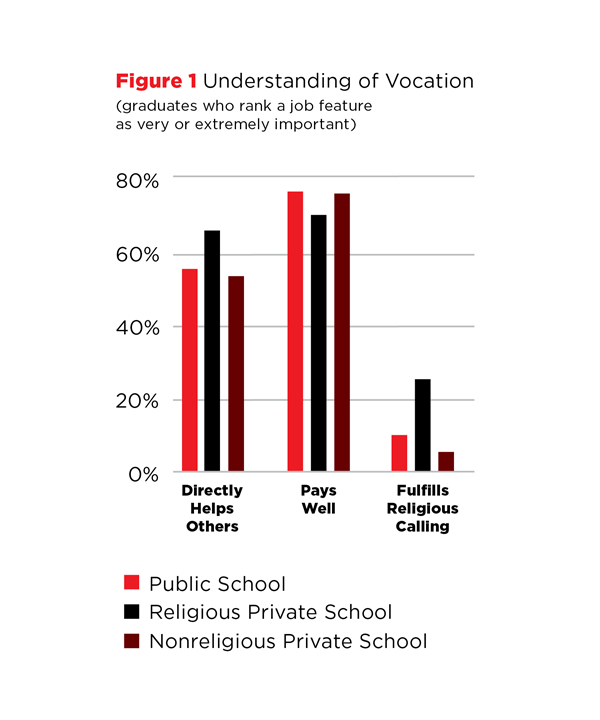

Christian college graduates are different from their peers at non-religious schools. When they think about work and finding a job, they value making a difference more and making money less.

According to a new study from the Christian think tank Cardus, two-thirds of graduates from private religious colleges and universities say it is important to them to find a job that “directly helps others”—10 percentage points higher than graduates from public schools or private nonreligious schools. About 70 percent of Christian school alumni said it was important to them to have a job that pays well, but that was 6 percentage points lower than other college graduates.

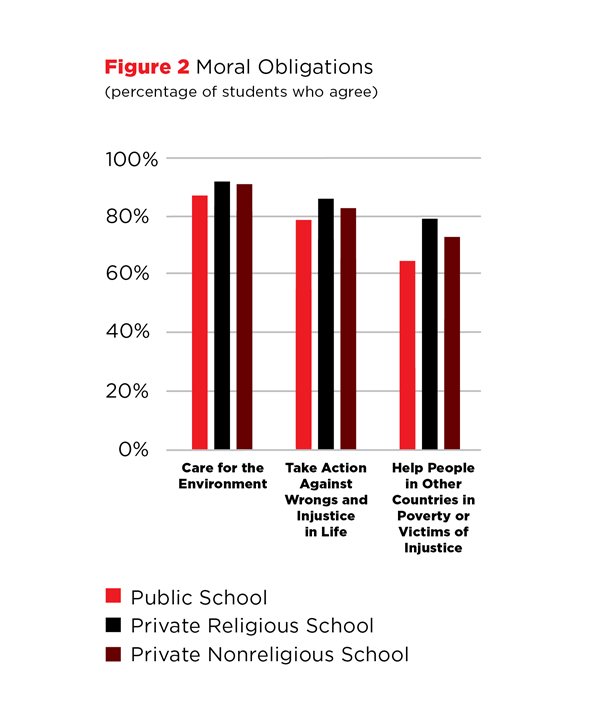

Graduates from religious schools also have a strong sense of moral obligation, according to the study. About 85 percent said it was important to “take action against wrongs and injustice in life.” Almost 80 percent said they should “help people in other countries in poverty or victims of injustice.” This is slightly higher rate than reported by other graduates: About 65 percent of public school alumni and about 73 percent of private non-religious grads feel obligated to oppose foreign poverty and injustice.

Graduates from religious schools are also a little more likely than their peers to feel a moral commitment to caring for the environment. More than 90 percent said that was very important to them.

Cardus, a nonpartisan Canadian-based organization that tries to “translate the richness of the Christian faith tradition into the public square for the common good,” has long been committed to demonstrating the value of Christian schools. This study, “What Do They Deliver?,” was co-authored by Albert Cheng, a professor of education reform at the University of Arkansas, and David Sikknik, a sociologist at the University of Notre Dame. They surveyed more than 1,300 graduates with four-year degrees from public and private, religious and non-religious schools in the United States and Canada.

Cheng said the goal of the study was to expand college administrators’ ideas of measurable output. Many small schools are facing financial crises and struggling to maintain enrollments. Religious institutions, in particular, are under pressure to defend their value to both donors and prospective students. Many of these schools make their case in terms of economic impact and spend a lot of time defending the economic value of a college education but don’t consider other factors, Cheng told Christianity Today.

“The language about return on investments and public impact, that’s what drives a lot of Christian colleges,” Cheng said. “We wanted to expand the conversation we have about what the value of post-secondary education is.”

The Cardus study provides what researchers think is a fuller account of what Christian higher education is actually doing in students’ lives—and why it matters to the students who graduate from these schools.

“These institutions are not just helping kids process ‘what I want to be when I grow up’ in terms of money and what I find to be fulfilling,” Cheng said, “but there’s a lot of conversation about what vocation really is.”

It is not clear from the Cardus study that Christian colleges’ formative education is what is causing graduates to care about making a difference and commit to this set of moral obligations. Separating correlation from causation is tricky. It might be that schools with a religious mission attract the kinds of students that care about these things. There’s some evidence in the study that high school seniors choose Christian colleges because they are already thinking about how they want to help people and make the world a better place.

Cheng and Sikknik asked graduates about their reasons for choosing a college. The top three reasons, across the board, were academic reputation, specific degree programs, and cost.

Only about 10 percent of students at Christian colleges and universities said their school’s religious mission was the primary reason they chose it. Fifty-five percent, however, said the religious mission mattered to them and factored into their choice.

According to Cheng, this could help college admissions offices as they think about recruiting students. It might be better to emphasize the way a Christian college is different from other schools.

“You know, in my town, we have a lot of restaurants, and when we get a new one, we always joke, ‘I hope it’s a burger place,’” Cheng said. “Because it’s like, how many burger places do we need? College is the same way. How many more job prep places do we need? There are people who want to dive into the formative aspect of education and we can serve them. What about being the place that asks the big questions and fosters connectedness to community and society?”

Cardus will be presenting the research to a Council for Christian Colleges and Universities’ conference for college administrators in San Diego on Wednesday.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month