Much of the switching in religious identity in the United States over the past several years occurred among the “nones,” specifically Americans who identify as agnostic or as “nothing in particular.” But the Christian landscape hasn’t remained static in the meantime.

Though academics have long wondered whether the US will follow the secularizing trend found in most of Europe, the greatest shifts among believers have occurred within Christianity, not away from it.

The three-wave Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES)—which surveyed the same individuals in 2010, 2012, and 2014, and started with 9,500 respondents—reveals how few Catholics and Protestants have changed affiliations and how many have moved from one denomination (or nondenomination) to another.

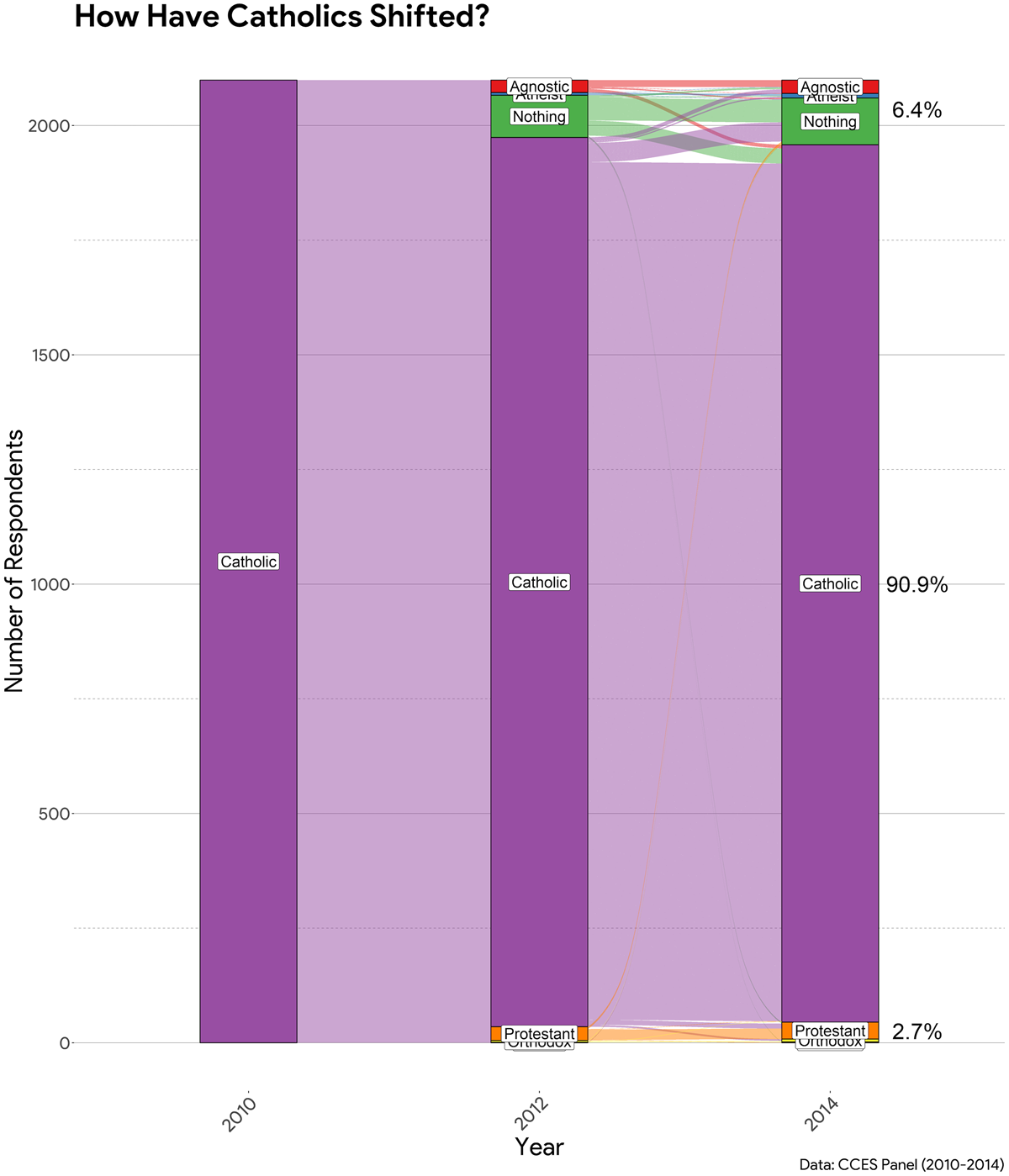

During this period, Catholics remained pretty attached to their tradition; they were about half as likely as Americans on average to change their affiliation: 8.8 percent vs. 18.9 percent. When Catholics do switch, they largely shift toward having no faith, with 6.4 percent switching to agnostic, atheist, or “nothing in particular.”

For Catholics, transitioning to another religious tradition is extremely rare. Of the 2,112 Catholics in the CCES sample, fewer than 50 left: 39 became Protestants, 6 became Orthodox Christians, and 3 became Buddhists.

The Catholic sample declined by 1 percent between 2010 and 2014, though this does not suggest a decline in Catholicism as a whole. (This data only includes individuals who switch into or out of Catholicism as adults, and excludes birth or death rates, which also have a tremendous impact on the total number of adherents.)

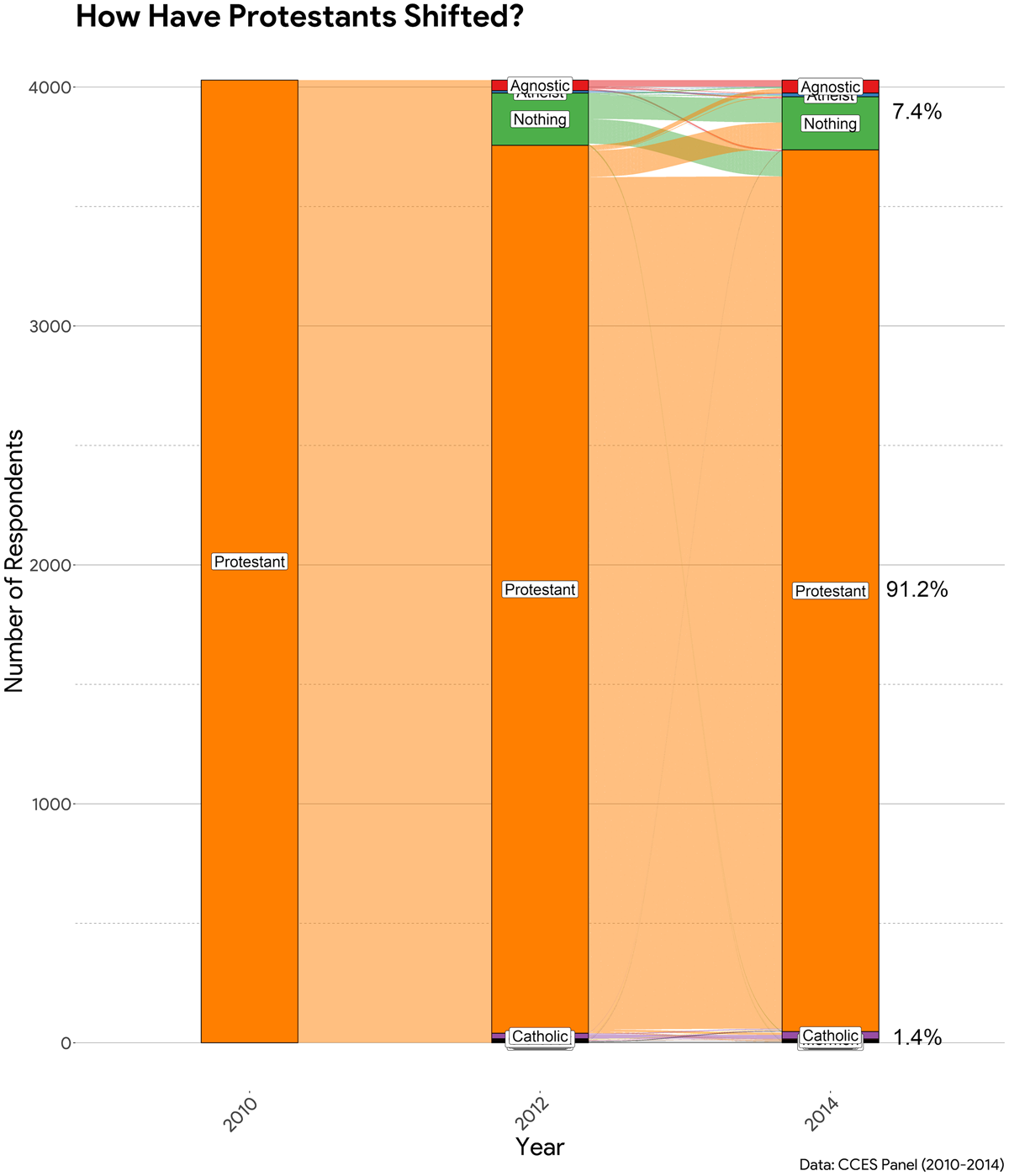

Protestants—the largest religious tradition in the US, making up 42 percent of Americans in the 2010 CCES panel—show similar patterns to their Catholic counterparts.

Protestants largely stay Protestant, defecting at similar rates as Catholics during the four-year period: 8.8 percent vs. 9.1 percent. The vast majority of those who leave Protestantism also become nones. Of those who identified as Protestants in 2010, 7.4 percent became nones by 2014, with 5.7 percent identifying as nothing in particular.

The number of Protestants who switched into another religious tradition is minuscule. Out of the sample of more than 4,000 Protestants, just 32 became Catholics, 7 became Buddhists, and less than 5 became Mormons, Jews, Muslims, or Hindus.

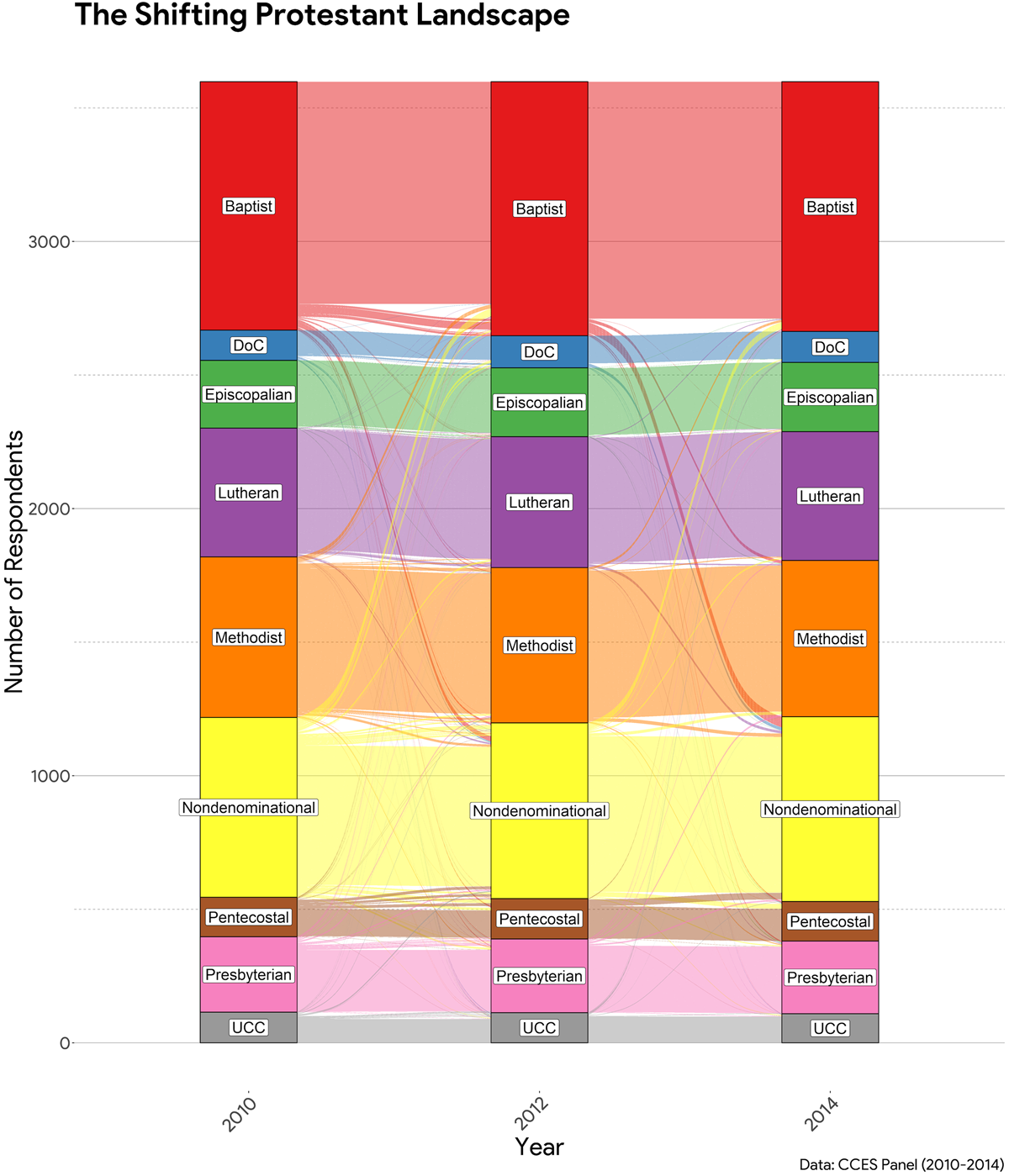

Though overall Protestant figures remain relatively steady, there is a tremendous amount of turbulence inside Protestantism.

While the Catholic Church is essentially unified, Protestantism is subdivided into a thicket of denominational traditions for Americans to switch between. The CCES lists 13 Protestant subgroups; some, like “Lutheran,” are composed of multiple denominations.

About 16 percent of all Protestants who stayed Protestant actually changed subgroups during the four years of the survey. Together with the 9 percent of Protestants who left, that means approximately one in four Protestants in 2010 had a different affiliation by 2014.

Outside of Baptists (22.9% of Protestants), the second-largest denomination is actually no denomination at all (18.2%). More Protestants identify as nondenominational—a relatively recent phenomenon in church history—than Methodists (14.8%) or Lutherans (11.8%). No other Protestant denomination makes up more than 7 percent of the overall Protestant tradition.

Even without tracking movement to or from specific denominations like the Southern Baptist Convention or the United Methodist Church, the CCES data shows the general trends in intra-Protestant switching. A great deal of activity centers around nondenominational churches.

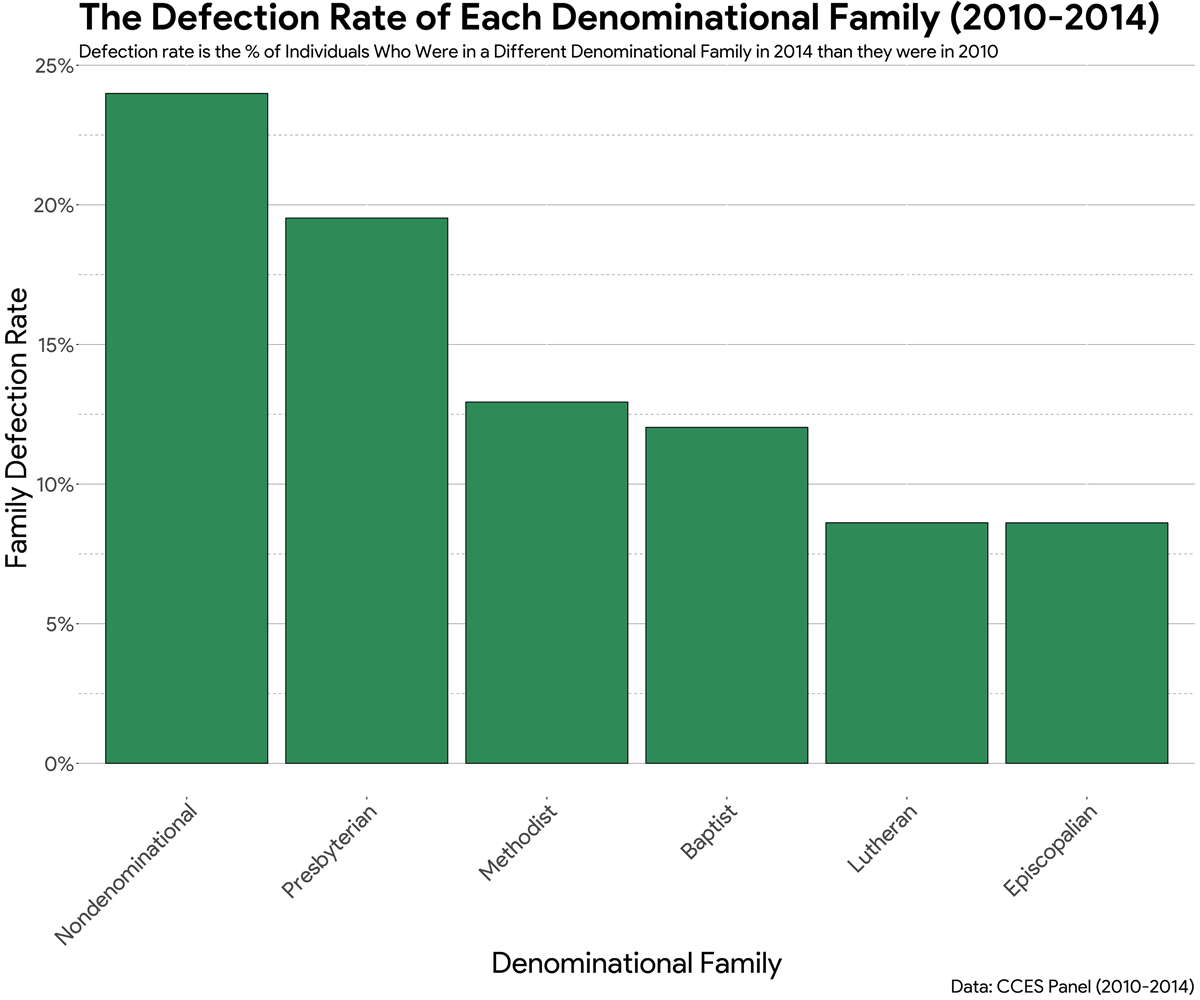

Not only is nondenominational Christianity among the largest affiliations, it also saw the highest rates of defection.

Nondenominational Protestants were more likely than Protestants in other traditions to shift their identity during the four-year period. Around 24 percent of those who claimed a nondenominational affiliation in 2010 switched—about double the volatility among Baptists and Methodists (12% and 12.9% respectively) and nearly three times that of Lutherans and Episcopalians (both at 8.6%) during the same time period.

The major denominational families that had the lowest amount of defections were the traditional mainline traditions, while nondenominational Christianity—almost always considered to be evangelical—had the greatest amount of defections.

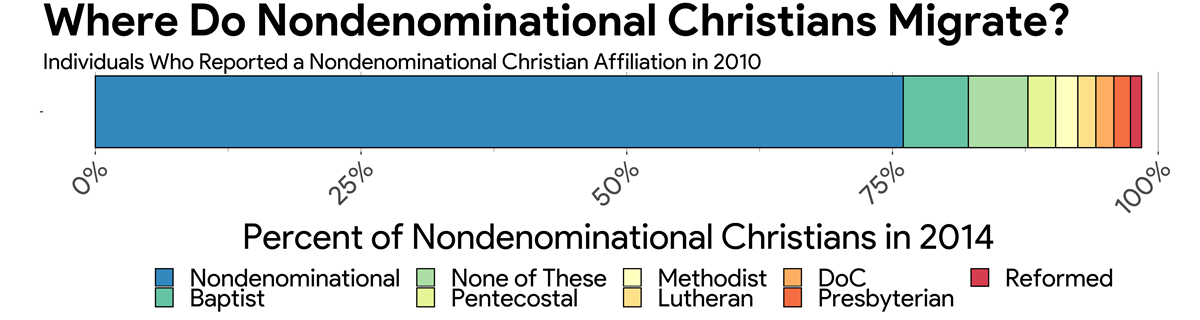

If nearly a quarter of nondenominational Christians are migrating to other Protestant traditions, where are they ending up? The answer is not straightforward. Of the 25 percent who leave, Baptists receive about 6.1 percent of switchers. The next most common move is for nondenominational Christians to go even more vague, with 5.6 percent selecting “none of these” on the CCES survey.

The best explanation for this pattern is that a lot of nondenominational Christians seem to know that they are Protestants but are not as knowledgeable about what type of Protestantism to claim. Because of this confusion, many waffle between the most innocuous options on the survey, with “nondenominational” Christian and “none of these” emerging as likely choices.

Protestant Christianity looks stable overall, with more than 9 in 10 Protestants staying that way over the years. But a tremendous among of migration lingers below the surface, particularly coming out of nondenominational Christianity.

Even though many of the largest churches in the US have emerged as nondenominational in affiliation, this tradition has not been able to protect its borders and identity. Fellow political scientist Paul Djupe has written about some of the possible downsides of nondenominational Christianity, including how the movement lacks an organizational structure to act in coordinated ways.

The popularity of nondenominational identity speaks to the declining “brand loyalty” among religious individuals. Though it’s possible that the trend is merely survey error: Individuals select nondenominational Christianity as an easy choice among the options on the list. This may serve as a word of warning to those leading nondenominational churches. While making it easier for individuals to join a nondenominational congregation might lead to dramatic increases in church membership, those weak ties may also lower the barrier for individuals to leave.

Ryan P. Burge is an instructor of political science at Eastern Illinois University. His research appears on the site Religion in Public.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month