This piece was adapted from Russell Moore’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

Moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt wrote this week in The Atlantic that we are all now living on the other side of the Tower of Babel.

Haidt, an atheist, doesn’t mean that literally, of course. The metaphor points to America’s fracturing into culturally tribal factions, which Haidt argues reached its tipping point in 2009, when Facebook pioneered the “Like” button and Twitter added a retweet function.

Although culture wars have always existed, these technological developments encourage triviality, mob mentalities, and the potential for everyday outrage like never before.

For Haidt, this descent into Babel means not a new culture war, but a different kind of culture war—where the target is not people on the other side so much as those on one’s own side who express any sympathy for the other side’s viewpoints (or even their humanity).

Political, cultural, or religious extremists whose goal is to produce viral content target “dissenters or nuanced thinkers on their own team,” making sure that democratic institutions based on compromise and consensus “grind to a halt.”

At the same time, Haidt contends, this sort of outrage-fueled, enhanced virality explains why our institutions are “stupider en masse” because “social media instilled in their members a chronic fear of getting darted.” This leaves the discourse controlled by a tiny minority of extremist trolls—all looking for “traitors,” “Karens,” or “heretics” to root out.

Haidt’s metaphor might be even more on point than he realizes. Babel, after all, was not just a technological achievement leading to fragmentation and confusion. It was rooted in two driving forces—which are also behind the outrage culture we are presently submerged in.

One of these is the desire for personal glory and fame: “Come, let us build ourselves a city, with a tower that reaches to the heavens, so that we may make a name for ourselves,” the Babel builders said (Gen. 11:4).

On any given day, we can see this dynamic at work in people who think the only way to build their personal “brand” is to attack someone they deem more significant—or to say something outrageous enough to draw out mobs of supporters and dissenters.

The other driving force is the desire for self-protection. The tower was necessary, the builders said, because “otherwise we will be scattered over the face of the whole earth” (v. 4). The technology was needed to forestall an existential threat.

So, what should a Christian posture be in this post-Babel world?

James Davison Hunter warned over a decade ago that much of American evangelical “culture war” engagement was based in a heightened sense of “ressentiment.” He said this went beyond resentment to include a combination of anger, envy, hate, rage, and revenge—in which a sense of injury and anxiety become key to the group’s identity.

Often, this sort of anxiety-fueled rage and revenge is bound up not with the fear of specific policy outcome but with a more primal fear more akin to middle school: the fear of humiliation. It feels like a kind of death—the kind that leaves one exposed and ridiculed by the outside world.

In Hunter’s view, a ressentiment posture is heightened when the group holds a sense of entitlement—to greater respect, to greater power, to a place of majority status. This posture, he warned, is a political psychology that expresses itself with “the condemnation and denigration of enemies in the effort to subjugate and dominate those who are culpable.”

It was no coincidence that Jerry Falwell Sr. named his political movement the Moral Majority. Hearkening back to Richard Nixon’s “silent majority,” the idea was that most Americans wanted the same values as conservative evangelicals but were stymied by coastal liberal elites who were able to rule over the wishes of most people.

Often, the most contentious aspects of American life center on the question “Who is trying to take America away from us?”—whether that be immigrant caravans overwhelming the border, the concept of American elites developing a global pandemic to control the population with vaccines, or the rhetoric of Satan-worshiping pedophile rings at the highest levels of government.

In her book High Conflict, Amanda Ripley writes that humiliation happens whenever our brains have conducted “a rapid-fire evaluation of events and fit it into our understanding of the world.” But that’s not enough. She argues, “To be brought low, we have to first see ourselves as belonging up high.”

To illustrate this, Ripley points to her once-ever golf outing, in which she missed the ball over and over again. She laughed at herself, she said, but didn’t feel humiliated because “being good at golf is not part of [her] identity.” However, if world-renowned golfer Tiger Woods performed the same way, he would feel humiliated, especially if his misses were caught on camera before a wide television audience.

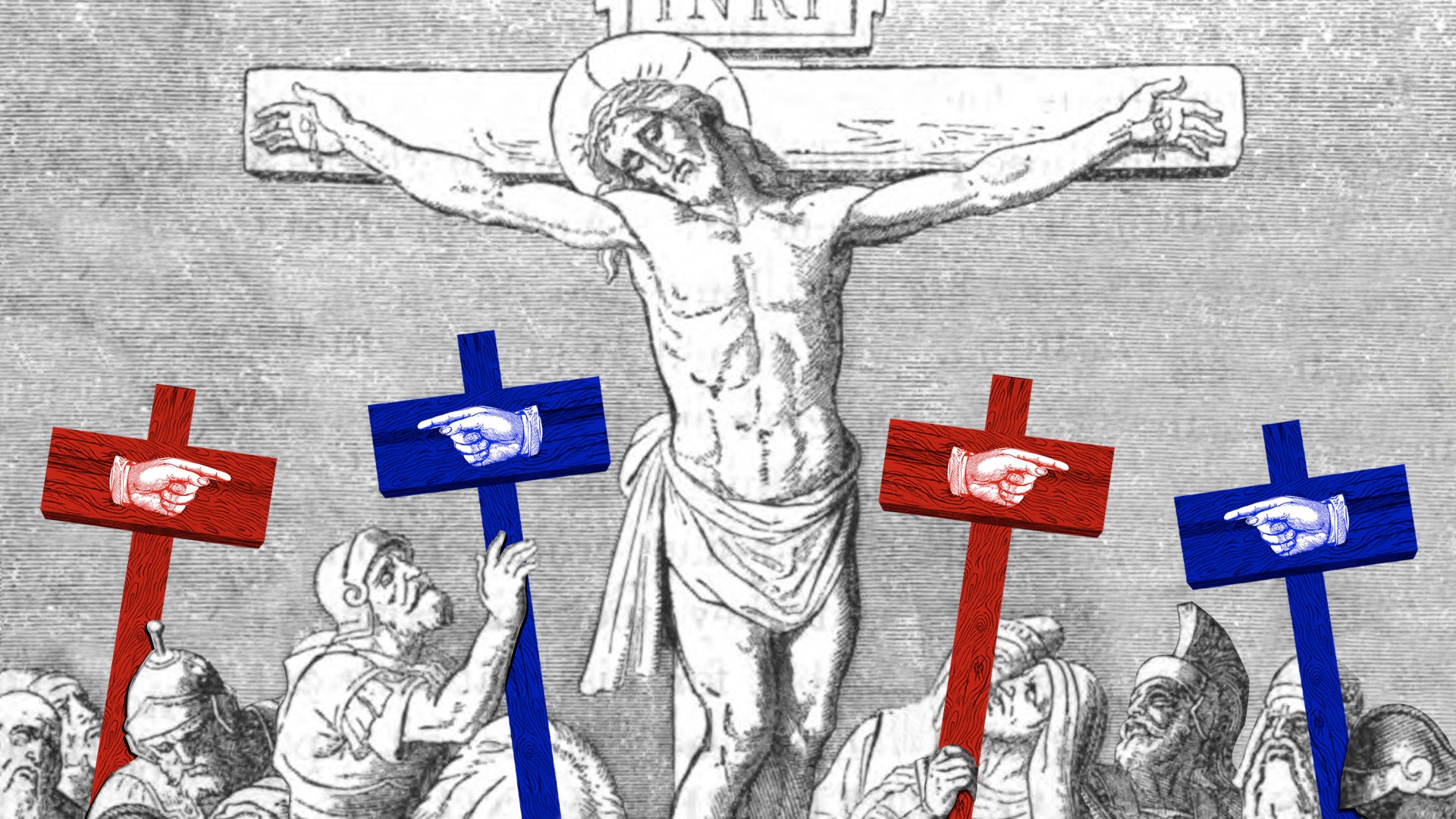

Yet the Cross is quite different. As Fleming Rutledge notes in her magisterial work The Crucifixion, there is no method the Roman Empire could have chosen to signify greater humiliation and domination than to crucify those who stood against its rule.

A cross not only ended a life but did so in the most ridiculing way possible—by magnifying Caesar’s domination over the one gasping for air on a stake. With Roman soldiers standing around and crowds screaming in rage and laughter, Good Friday looked like the triumph of Babel, right down to the signs in multiple languages over the head of the crucified King.

And yet Jesus spoke of this downward trajectory as the way in which he would be “lifted up” and would “draw all people to himself” (John 12:32). This stands in contrast not only to those who sought to magnify their own name, such as Caesar who wanted no rivals to his reign, but also to those who sought their own self-protection, like the disciples who fled in fear.

Only the crucified Christ—the sin-bearing Lamb of God—vindicated by the resurrecting power of his Father, could pour out the Spirit in a way that could reverse Babel at Pentecost.

But the Resurrection and Ascension were not an undoing of the Crucifixion. They were, instead, a continuation of what Jesus pronounced to be a triumph through defeat, a power through weakness. As New Testament scholar Richard Hays once noted, after his resurrection Jesus did not appear to Pilate or to Caesar or to Herod. To do so would have been to vindicate himself—to win an argument rather than to save the world.

Instead, as Luke puts it, Jesus “presented himself alive” (Acts 1:3, ESV) to those he had chosen as witnesses. That’s because Jesus’ kingdom would advance not through resentment and grievance but through those who would bear witness to him with sincerity and truth, even to the loss of their own lives. Conquering like that—through “the blood of the Lamb and by the word of their testimony” (Rev. 12:11)—is what winning looks like, especially when one sees who the Enemy actually is.

Experts tell us to expect the next few years to be worse than the previous ones. Those who seek to make a name for themselves by exploiting fear and outrage will continue to get better at it. And they will not lack an audience of those who believe the only thing standing between them and annihilation is the requisite amount of theatrical anger.

Culture wars and outrage cycles might fuel ratings and clicks and fundraising appeals, but they cannot reconcile sinners to a holy God. They cannot reunite a fragmented people. They cannot even make us less afraid in the long run.

Good Friday should remind us that, as Christians, adding more outrage and anger to a culture already exhausted by its own is not how God defines his wisdom and power. Babel building can’t help us—only cross carrying can.

Russell Moore leads the Public Theology Project at Christianity Today.