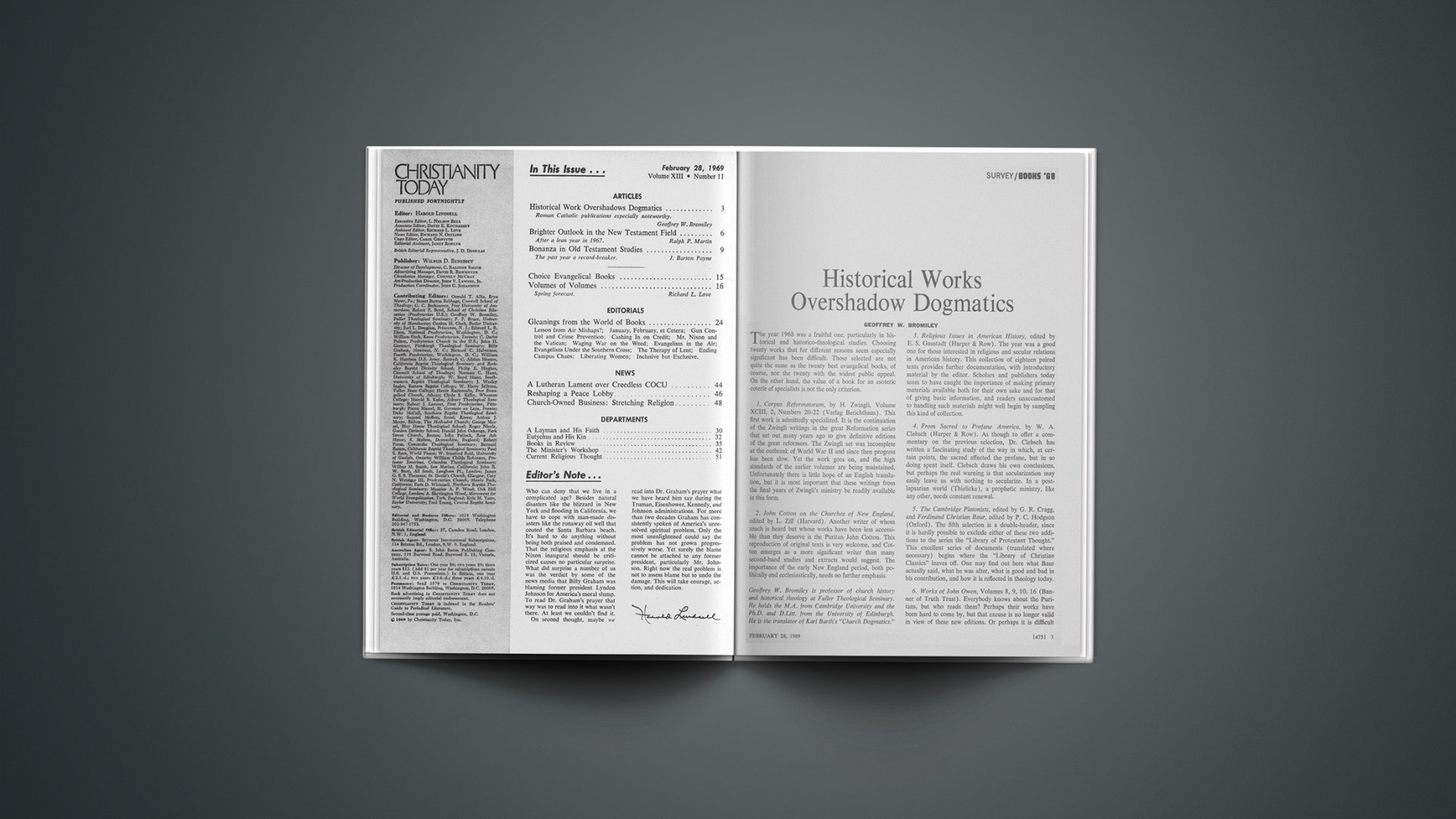

The year 1968 was a fruitful one, particularly in historical and historico-theological studies. Choosing twenty works that for different reasons seem especially significant has been difficult. Those selected are not quite the same as the twenty best evangelical books, of course, nor the twenty with the widest public appeal. On the other hand, the value of a book for an esoteric coterie of specialists is not the only criterion.

1. Corpus Reformatorum, by H. Zwingli, Volume XCIII, 2, Numbers 20–22 (Verlag Berichthaus). This first work is admittedly specialized. It is the continuation of the Zwingli writings in the great Reformation series that set out many years ago to give definitive editions of the great reformers. The Zwingli set was incomplete at the outbreak of World War II and since then progress has been slow. Yet the work goes on, and the high standards of the earlier volumes are being maintained. Unfortunately there is little hope of an English translation, but it is most important that these writings from the final years of Zwingli’s ministry be readily available in this form.

2. John Cotton on the Churches of New England, edited by L. Ziff (Harvard). Another writer of whom much is heard but whose works have been less accessible than they deserve is the Puritan John Cotton. This reproduction of original texts is very welcome, and Cotton emerges as a more significant writer than many second-hand studies and extracts would suggest. The importance of the early New England period, both politically and ecclesiastically, needs no further emphasis.

3. Religious Issues in American History, edited by E. S. Gaustadt (Harper & Row). The year was a good one for those interested in religious and secular relations in American history. This collection of eighteen paired texts provides further documentation, with introductory material by the editor. Scholars and publishers today seem to have caught the importance of making primary materials available both for their own sake and for that of giving basic information, and readers unaccustomed to handling such materials might well begin by sampling this kind of collection.

4. From Sacred to Profane America, by W. A. Clebsch (Harper & Row). As though to offer a commentary on the previous selection, Dr. Clebsch has written a fascinating study of the way in which, at certain points, the sacred affected the profane, but in so doing spent itself. Clebsch draws his own conclusions, but perhaps the real warning is that secularization may easily leave us with nothing to secularize. In a postlapsarian world (Thielicke), a prophetic ministry, like any other, needs constant renewal.

5. The Cambridge Platonists, edited by G. R. Cragg, and Ferdinand Christian Baur, edited by P. C. Hodgson (Oxford). The fifth selection is a double-header, since it is hardly possible to exclude either of these two additions to the series the “Library of Protestant Thought.” This excellent series of documents (translated where necessary) begins where the “Library of Christian Classics” leaves off. One may find out here what Baur actually said, what he was after, what is good and bad in his contribution, and how it is reflected in theology today.

6. Works of John Owen, Volumes 8, 9, 10, 16 (Banner of Truth Trust). Everybody knows about the Puritans, but who reads them? Perhaps their works have been hard to come by, but that excuse is no longer valid in view of these new editions. Or perhaps it is difficult to get through to their style and thought. This comes only by trying; the rewards are at least commensurate with the effort, far more so than in the case of many of our even more unintelligible modern authors.

7. Liberal Protestantism, edited by B. M. G. Reardon (Stanford University Press), in the series “Library of Modern Religious Thought.” Before leaving the extensive field of sources we should note this useful volume of extracts from the greater liberals, including Ritschl, Hermann, and Harnack. Some will welcome this book for the support it may give resurgent liberalism, but the real point is again that exact presentation replaces second-hand portrayal, and a proper assessment of the good and the bad may thus be made. An alternative or companion volume is the Harper Torchbook The Liberal Era, and by way of counterblast see The American Evangelicals, 1800–1900, both from Harper & Row.

8. The Byzantine Empire, II, edited by J. M. Hussey (Cambridge), Volume IV of the “Cambridge Medieval History” series. Through the years this series has shown its worth, and the current revision will undoubtedly extend its usefulness. This volume has quite a few sections dealing with religious aspects of the Byzantine world. This world may seem chronologically and geographically remote, but the matters dealt with are by no means dead or irrelevant. Who dares say that the Balkans and the Eastern Orthodox churches are of no interest to us?

9. The Early Vasas, A History of Sweden 1523–1611, by M. Roberts (Cambridge). Talking of remoter areas reminds us of another excellent study that fills in what is for many a very skeletal outline, that of Swedish history during the crucial Reformation period. Since the Scandinavian countries are small it is easy to overlook the important role they played at this juncture, their contribution to the making of modern America, and the pivotal place of the Lutheran Church of Sweden in the ecclesiastical world today. This very good work fills a real need.

10. Sacramentum Mundi, An Encyclopedia of Theology, Volumes I and 11, edited by Karl Rahner (Herder and Herder). From the Roman Catholic world comes one of the great productions of the century, the new encyclopedia that has been in preparation since Vatican II and is published in French, German, Dutch, Italian, and Spanish as well as English. Among the renowned contributors are Rahner, Küng, Baum, and Schillebeeckx. What can one say of a work of this kind? It is an encouraging reflection of the new trend, sets the pace for comparable evangelical work, gives tremendous emphasis to the Bible, and yet also gives evidence that the new look contains at least the sinister possibility—may it never be more!—of becoming a new modernism.

11. Dictionary of Biblical Theology, edited by X. Leon-Dufour (Chapman). This, too, is a Roman Catholic work, a single-volume dictionary published some years ago in French and now made available in English. It offers a less expensive and more compendious alternative to Sacramentum Mundi with a particular reference to biblical themes and with all the grace and clarity of French style. The articles are refreshingly biblical, though the irreformability of Roman Catholic definition casts a long shadow at some points.

12. An Introduction to the Theology of Rudolf Bultmann, by Walter Schmithals (SCM). For those who find it hard to read or understand Bultmann’s own works but are suspicious of tendentious representations, this translation of Schmithals’s work is a handy guide. Schmithals is a former pupil and not entirely unbiased. Yet his aim is correct and orderly presentation rather than evaluation. He writes in order that general students may make their own judgment on the basis of solid information instead of engaging in naïve applause, misdirected application, or ill-informed condemnation. He performs this task admirably, and an alert student will come away with far better reasons for the necessary repudiation of Bultmann’s theology.

13. What’s New in Religion?, by Kenneth Hamilton (Eerdmans). Why one must make this repudiation, though not just of Bultmann, is clearly and trenchantly shown in this new little book by Professor Hamilton. In it he tackles the new theologies and moralities of such men as Robinson, Tillich, Cox, and Fletcher. To thorough knowledge he adds an understanding that enables him to expose the vital weaknesses of the neologies, and to both he adds an entertaining style that makes him readable and strengthens rather than weakens his plea for a true theology.

14. The Reality of Faith, by H. M. Kuitert (Eerdmans). Another effective reply to current neologies is the work by the professor of ethics at the Free University of Amsterdam. Kuitert rightly grasps the essential objectivity of Christianity, yet also sees that this does not mean a handling of Christian doctrines merely as metaphysical truths. The objectivity is that of history, the history that of God at work among men. Hence theology is a pointing to reality. It also involves doing as well as believing and speaking. The book thus becomes more than a reply. It is a positive statement to lead us beyond the false dilemmas of the last few centuries.

15. Pelagius: Inquiries and Reappraisals, by R. F. Evans (Seabury). Heresies are stubborn. This is especially true of Pelagianism, which perhaps enshrines man’s most deep-seated resistance to the Gospel. Yet Pelagius is better known for what became of his teachings than for what they initially were. This fresh investigation, the first in a series, is thus a timely one that should interest historians, dogmaticians, and indeed all Christians. It helps to get the picture in clearer focus. It also brings the focus on the British (and American!) heresy that finds representatives in almost every theological group.

16. The Christian Understanding of the Atonement, by F. W. Dillistone (Westminster). The year was not very rich in dogmatic studies. The atonement, however, rightly continues to claim attention, and Dr. Dillistone has made a scholarly and thoughtful contribution in his latest book. In some sense all works on the atonement are disappointing; who can grasp its fullness? Hence it is easy enough to find defects in this new study. Yet God’s reconciliation is so full that there is something to learn from every positive discussion. Although perhaps no one will agree with all that is said, no discerning reader should leave this work without some profit.

17. John Knox, by Jasper Ridley (Oxford). In biography, too, the year was a poor one. Jasper Ridley, however, has added to previous books on Ridley and Cranmer this full-scale account of the Scottish reformer John Knox. Ridley is an experienced historian who has been able to dig up some new materials, check out previous biographies, and make new suggestions, all within the compass of a well composed and well written narrative. His greatest weakness is a lack of dogmatic flair or training, which reduces the value of the theological exposition and evaluation, so important in relation to the reformers. But the work is worthy of attention as a straightforward biography.

18. The Theses Were Not Posted, by E. Iserloh (Chapman), and Martin Luther’s 95 Theses, by K. Aland (Concordia). Some historians have a curious taste for debunking the dramatic in history, and the nailing up of the Ninety-five Theses, now an integral part of Hallowe’en for Protestants, has recently been relegated to the other world of the vigil by Dr. Iserloh. Good Lutherans, who have already had troubles with the inkpot, cannot allow this to happen to the Theses too, and the doughty champion K. Aland has come forward to defend a real posting. (So far the composition has not been challenged.) All quite entertaining, but one fears for the burning of the papal bull—a bad precedent in these days of university disturbances.

19. The Lord’s Day, by W. Rordorf (Westminster). Pastorally this study of Sunday deserves attention for its methodology, its solidity, and the essential—if to some people unwelcome—soberness of its findings. Rordorf sees that proper practice depends on a proper basis, and his work is devoted mainly to biblical and historical study. The greatest weakness is the failure to bring together the themes of worship and rest in the discussion. Rordorf then shows what proper observance involves on this foundation. Those who defend a cavalier treatment of the Lord’s Day by sophistries about Law and Gospel or cultural diversity might do well to read a work of this kind. Those who sense its inadequacies might provide the theological basis for the position they commend.

20. New Oxford Dictionary of Music, Volume 4: The Age of Humanism, edited by G. Abraham (Oxford). Church music is an important pastoral field, and almost all Christians are affected or interested in some way. This is a good reason for musical education among organists and pastors who insist in having a hand in musical selection. A series like the “New Oxford Dictionary” is an important tool in this regard, especially in so far as it deals with church music. It might even help to provide basic material for the education of congregations, whose appreciation at least can surely outrun their capabilities. This is a primary work for “choirs and places where they sing.”

In conclusion brief note may be made of some other significant 1968 works. Among documents are The Antinomian Controversy, edited by D. D. Hall (Wesleyan University), and The Beginnings of Dialectical Theology, edited by J. M. Robinson (John Knox). Historically W. H. C. Frend writes with his usual distinction on Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early Church (Doubleday), Gordon Donaldson handles the Scottish Kings, and C. G. Bolam et al. present The English Presbyterians (Allen and Unwin). Institutional problems engage J. Pelikan in Spirit Versus Structure (Harper & Row) and H. Küng in Structures of the Church (Notre Dame). An important book is that of E. Schillebeeckx on God—The Future of Man (Sheed and Ward). J. Jocz of Toronto has a new and stimulating study of The Covenant (Eerdmans). H. Küng has put together some of his lecture material in Truthfulness (Sheed and Ward), while J. Knox is still worrying about Myth and Truth (Carey Kingsgate). A tribute of interest to evangelicals is paid in The Philosophy of Gordon Clark, edited by R. H. Nash (Presbyterian and Reformed). The problem of anti-Semitism has produced two informative studies, one on The Vatican Council and the Jews, by A. Gilbert (World), the other on The French Enlightenment and the Jews, by A. Hertzberg (Columbia University). Pastors will find much food for thought in the original essays of O. Hartman on Earthly Things (Eerdmans), and for Roman Catholics K. Rahner digs into The Theology of Pastoral Action (Herder and Herder). Finally, Roman Catholic uneasiness about papal infallibility has found amazingly open expression in Francis Simons’s book entitled Infallibility and the Evidence (Templegate): the amazing thing here is that this Roman Catholic bishop in India does not think the evidence provides any true support for infallibility. The increasing quantity, the vigor, and the quality of Roman Catholic publications are among the most striking features of this whole field of theological literature today. It is a challenge to liberal Protestants to turn their talents back to serious theological work in place of the dominant neologizing, and to evangelical Protestants to address themselves to the task of producing a comparable body of historical and theological writings—partly in harmony, partly in dialogue, and partly still in tension, with their Roman Catholic counterparts.