When people discover that I have a child with Down syndrome, I often receive a murmur and a sympathetic nod of the head. I almost immediately feel something tighten inside my chest, as if I am steeling myself for a fight my opponent doesn’t even know they’ve initiated. Most of the time, that person talking with me is trying their best. Unless they have a family member or friend with Down syndrome, their impressions of our family life come from vague or stereotypical media portrayals. I know my own reaction when we found out, two hours after Penny was born, that her body contained a third copy of chromosome 21. Fear, anger, guilt, sadness. That’s what I felt, and that’s what many people expect when they talk to me about Penny.

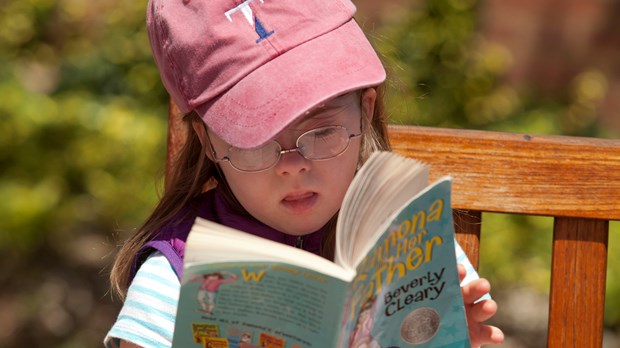

But when I talk about Penny with a new person, I want to share the same types of things I would share about any of my kids. I want to share the joy of being her mom, the funny things she says, her love of music even though she sings off-key, her goal for the year of doing a handstand, her precocious reading ability, her Gumby-like body that allows her to flop into poses I could never imagine for myself.

It’s not that there’s nothing difficult about having a child with Down syndrome. It’s just that starting with the hardship betrays her, as if difficulty marks my life as a parent instead of love or joy.

We do go to the doctor more with Penny—regular visits to the orthodontist, ophthalmologist, otolaryngologist, physiatrist and I’m supposed to check in with the cardiologist sometime soon. Penny works with a physical therapist, an occupational therapist, a speech therapist, and a special education teacher at school. Her low-muscle tone brings with it some advantages—she is a lovely ballerina—but it also means her fingers fumble over buttons and she needs braces on her ankles and her handwriting is often hard to read. And Penny learns things more slowly than typical kids. Math concepts have not come easily, and although she reads all the time, she often needs to read a chapter book cover to cover more than once before she can articulate the story inside.

But these challenges are not the types of things that come to mind when I am telling a new person about our family. And the sympathy I desire from other people comes more from being a mother of three children than a mother of any particular child. When I think about the hardship of being a parent, I think about cajoling Penny into brushing her teeth instead of lounging under the covers, and trying to teach William to sleep past 5:30 a.m., and responding to the panic in Marilee’s eyes last week when she swallowed a coin. I think about how hard it has been for me to give up my autonomy, to barter for time with my husband, to sacrifice comfort and energy and desire. It’s been hard for me to watch my spiritual life, my emotional life, my physical life, my life—become messy and chaotic. It’s been hard for me to accept the mundane realities of my life as a mother. But being a parent of a child with Down syndrome has just been a part of the hardship—and joy—of this stage of my life, of growing up.

October is National Down Syndrome Awareness Month. There are plenty of ways to advocate for inclusion of children and adults with Down syndrome in schools and faith communities and the workplace. There are plenty of injustices to protest and causes to champion. But maybe the place to start is with awareness that the vast majority of people with Down syndrome enjoy their lives, and the vast majority families of people with Down syndrome welcome their presence.

I love it when I tell people that Penny has Down syndrome and they are able to ask me about her as a full person, when they assume that she’s a kid with gifts and challenges. I love it when people say, “Tell me about your daughter!” with a smile. I’m so much more inclined to tell the whole truth—the hard things and the joyful gifts—when I’m talking with someone who seems to assume my daughter is not a burden or an angel but just my daughter.

Our daughter Penny. At times infuriating. At times bewildering. But always beloved. Always a gift.

Support our work. Subscribe to CT and get one year free.

Recent Posts

How to Talk to Parents of Children With Down Syndrome

How to Talk to Parents of Children With Down Syndrome

How to Talk to Parents of Children With Down Syndrome

How to Talk to Parents of Children With Down Syndrome