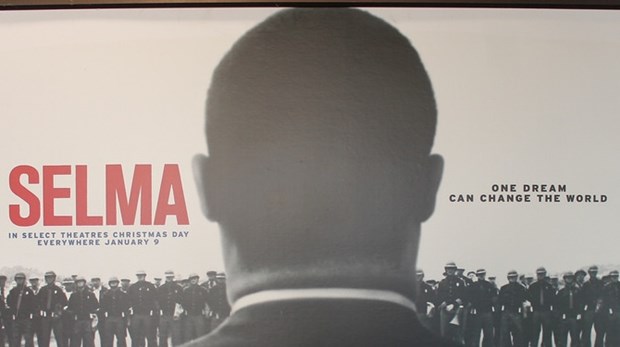

First, a brief overview in case you haven't seen it: Selma, a biopic directed by Ava Duverney, tells the story of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. during the historic march from Selma, Alabama to the state capital. Duverney focuses on this short period of time as a way to magnify the various issues at stake during the Civil Rights Era. In this case, the conflict centers around giving African Americans the right to vote, and the film remains focused on a short time period during the early spring of 1965. It brings up the relationship between the federal government, local activists, and state regulators. It explores King’s role as a leader, a husband, a father, and as a man of faith. And it offers a visceral portrayal of the horrific violence perpetrated against African Americans and their allies throughout this struggle.

The film came under criticism mainly for its portrayal of the relationship between President Lyndon Johnson and Dr. King. Historians claim LBJ offered far greater support for King’s efforts than Selma Suggests, and they claim the film portrays LBJ as a villain of sorts. I didn’t think the film deserved this degree of criticism—LBJ and MLK make it clear early on in the film that Johnson is a politician and King an activist, and to get to a voting rights bill they will necessarily have to antagonize one another. Moreover, if Duverney—an African American woman—gave us a view of history that emerged out of the African American experience of waiting and waiting and waiting for justice, well, from that perspective Johnson took too long and could have done more. Johnson supported King, but he still had an FBI director in J. Edgar Hoover who mistrusted King and his movement, and he still needed to attempt to satisfy all his constituents, including the white southerners opposing civil rights.

Moreover, when it comes to the Academy Awards, accurate history hasn’t exactly been the gold standard. Ava Duverney did not receive a nomination as director for Selma, but Oliver Stone received one for JFK, as did Steven Spielberg for Lincoln, even though both films also came under scrutiny by historians. Perhaps Neal Patrick Harris had it right last night when he joked about welcoming “Hollywood’s best and whitest, I mean brightest” last night.

But even if the criticisms of this film are spot on and Duverney didn’t deserve the nomination, and even if other films had more artistic merit, I wish Selma had won Best Picture last night because whatever its flaws, Selma succeeds in telling a story that has the power to transform us. First, Selma portrays a very real person. We see King’s deep flaws in his betrayal of his wife. We see his uncertainty as a leader when the decisions he makes lead to death and injury. We also see his strength and courage and the way he calls forth the best in himself and in others. He is a Christian leader, sinful, broken, and filled with sacrificial love and courage. As remarkable as King was (and as remarkable as David Oyelowo’s performance was too), he was also just a man who remained faithful to his calling, even at the cost of his life.

Moreover, both my husband and I walked out of Selma with a deeper desire to do justice, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with our God. Both of us walked out with a deeper belief that human beings can be conduits of the kingdom of God among us—of hope and peace and love amidst hatred and violence. Selma taught us about an important chapter in American history. More importantly, it reminded us that we are participants in that ongoing history. It reminded us of the power of each life to work for good, to surrender our desires to the will of God, and to participate in God’s ongoing work to transform, to redeem, to bring peace.

The only award Selma received last night was for “Glory,” the John Legend and Common song that combines the power of the African American musical tradition—gospel and hip hop together—to convey through music the emotional and spiritual power at this film’s core. “Glory” retains a prophetic voice to critique not only the past but also the present for American race relations. It also holds up the hope not for human beings to make it all work out, but for God’s glory to be upheld, to triumph over injustice, to be victorious in the end.

I wish the Academy had nominated Duverney and Oyelowo. I wish Selma had won Best Picture. Perhaps more importantly, I hope Americans of all colors will watch this film, listen to this song, and allow the story it tells to transform us into people who believe God’s glory can change the world through us.

Support our work. Subscribe to CT and get one year free.

Recent Posts

Why I Wish Selma Had Won Best Picture

Why I Wish Selma Had Won Best Picture

Why I Wish Selma Had Won Best Picture

Why I Wish Selma Had Won Best Picture