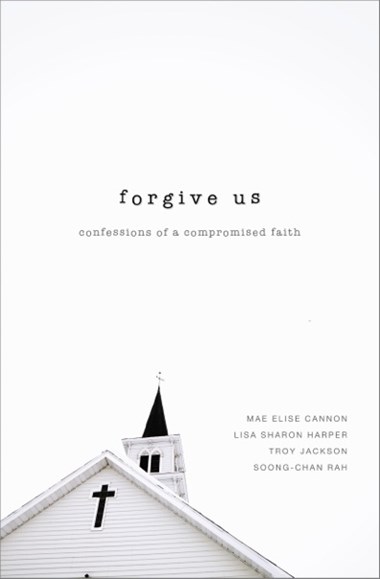

In the midst of the national news storm that emerged following Michael Brown's death in Ferguson, Missouri, this summer, I received an early copy of Forgive Us: Confessions of a Compromised Faith. This book, written by four evangelicals from a variety of ethnic backgrounds, came out in September. If the events in Ferguson (which are ongoing) demonstrate anything, it is the timeliness of a book that seeks healing around the area of racial reconciliation. The book goes farther than race, however, and looks at topics from sin against God's creation to sin against people based upon religion and sexuality. I had the opportunity to interview two of the book's authors via email:

How did this book come about? Were there any particular events that prompted this response?

Mae: Troy Jackson came to me at the Christian Community Development Conference (CCDA) some years ago in Cincinnati, Ohio. He was serving as a pastor at the time and felt convicted that his church, and the broader Christian community, was ignoring ways Christians have contributed and benefit from systemic injustice. He asked if we could collaborate. I was already in community with Lisa Sharon Harper and Soong-Chan Rah through a group called Evangelicals for Justice (E4J). This project seemed right up their ally. We pursued the author team with the hopes that the four of us could live out a small glimpse of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s beloved community.

Can you point to times in ancient or recent church history when Christians have practiced corporate repentance?

Soong-Chan: We can clearly see Scriptural examples of corporate repentance. Jeremiah and the book of Lamentations jump to mind. As does the example we use in our book, Nehemiah. I think we tend to pick and chose our prayers according to our cultural biases. In recent history, we have focused on a hyper-individualistic approach to spirituality which tends to negate corporate repentance. But I think of the example of a group of Japanese Christians who corporately confessed historical sins to a group of Korean Christians. I think of the Truth in Reconciliation movement in South Africa. And even in the US, a recent act of public corporate repentance over the issue of slavery (and again, here).

Why should Christians take responsibility for problems that in some cases originate and extend beyond the church?

Mae: The church is a microcosm of its larger community. It is full of broken people who are seeking to worship God, live together in community, and be transformed by the presence of the Holy Spirit in their lives. The sins discussed in Forgive Us are woven throughout the very fabric of our church communities in the United States. The church might not be the primary organizational body behind a certain systemic injustice, but sometimes it is! Either way, the community of believers benefits from the structures and systems within its larger community. And often it is church-attending individuals who are leading institutions of power which are broken and in need of redemption. Christians must model taking responsibility and repent for the ways societal ills are perpetuated and must be committed to responding to the needs of the poor, the downtrodden, and the oppressed.

How would you describe evangelicals' current and historical relationship to social justice?

Mae: Historically, the church in the United States, including evangelicals, has been very engaged in responding to the needs of the poor, acts of charity, and ministries of justice. Christians and churches throughout the 19th century started programs addressing societal problems such as poverty, orphaned children, widowed women, and the elderly. With the dawn of the 20th century, acts of compassion, charity, and justice became increasingly privatized. President Roosevelt’s New Deal initiative established government systems designed to provide relief to Americans suffering from poverty as a result of the Great Depression. Social work became a professional discipline and the “work” of responding to the needs of the least of these shifted from the church toward other systems and institutions such as private enterprises, non-profit organizations, and the government. In the 21st century, there is a growing movement of young evangelicals who see the integration of justice as a critical component of their understanding of the Gospel of Christ.

What does corporate confession have to do with the gospel, with spreading the good news?

Soong-Chan: Corporate confession is a part of embracing the gospel truth that all have sinned and continue to fall short of the glory of God. Part of the good news is that we are saved from sin and unrighteousness, and a part of that spiritual reality should also include corporate sin. I also think it is a powerful example to the world of Christian love. That we set an example of loving our brothers and sisters in Christ by seeking their forgiveness. It demonstrates that we care about the issues and concerns that break their hearts. Originally, we had envisioned that this book would actually be read by a non-Christian audience. Our hope was to model the repentance that is so essential to the gospel.

You cover a wide range of topics in this book, and it can feel overwhelming to think of engaging them all for positive change. What actions would you recommend for Christians who feel helpless in the face of such big problems?

Mae: The subtitle of my first book is Small Steps for a Better World. All of us can’t do everything, but we all can do something to work toward positive change. Forgive Us provides the opportunities for individuals and communities to enter into the spiritual discipline of confession as a means of beginning to own ways we have contributed knowingly or unwittingly to injustices in our communities and around the world. Prayer and spiritual discernment is a great place to start as we ask God the question of what role we might play in actively engagement in ministries of compassion while advocating for justice.

What work are you doing to effect the kind of repentance and change you call for in Forgive Us?

Soong-Chan: I personally seek to model not only repentance but a changed heart and a changed life through repentance. I am reminded of our friend, the late Richard Twiss, to whom we dedicate our book, who called us not only to repent of our sins, but more importantly to walk alongside him in his struggles as a Native American Christian. Confession can lead to reconciliation which leads to a community that walks and serves together. I hope to model that kind of reconciled community in my personal relationships. In how I model a life of humility and repentance by advocating for my brothers and sisters. I hope this book calls us to not only engage in the act of a needed public confession for the sins of the church, but also changed hearts and lives as Christians and as the church, that changes how we engage others

We and our co-authors are involved in numerous corporate and individual pursuits to bring the issues we address in our book to the forefront of the American religious and political scene today. Lisa Sharon Harper and Troy Jackson were, for example, on the ground in Ferguson recently, encouraging and organizing churches there in visible response to the myriad problems for which Christian are--at least in part--responsible. In our traveling, writing, and teaching, we strive to paint a full picture of the reconciliation the gospel both requires and makes possible.

Mae Elise Cannon (PhD, University of California-Davis; MA, Trinity International University; MBA, MDiv, North Park University) is senior director of advocacy and outreach for World Vision USA. An Evangelical Covenant Church pastor, Cannon is author of the Social Justice Handbook: Small Steps for a Better World and Just Spirituality: How Faith Practices Fuel Social Action.

Soong-Chan Rah (MDiv, DMin, Gordon Conwell Theological Seminary; ThM, Harvard University) is Milton B. Engebretson Professor of Church Growth and Evangelism at North Park Theological Seminary in Chicago, Illinois. The author of The Next Evangelicalism: Freeing the Church from Western Cultural Captivity and Many Colors, Rah was formerly the founding Senior Pastor of Cambridge Community Fellowship Church, a multi-ethnic, urban ministry-focused congregation in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Support our work. Subscribe to CT and get one year free.

Recent Posts

Confession Leads to Reconciliation Leads to Community

Confession Leads to Reconciliation Leads to Community

Confession Leads to Reconciliation Leads to Community

Confession Leads to Reconciliation Leads to Community