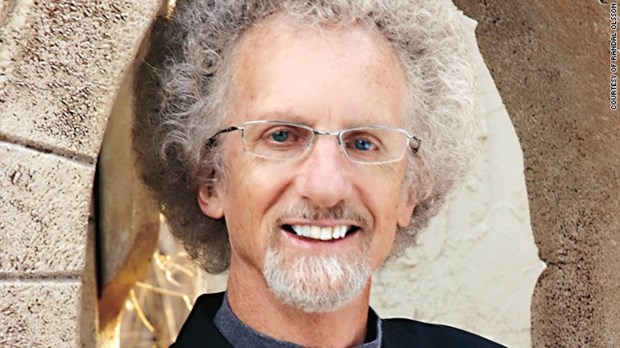

I had the privilege of talking by phone with Philip Yancey about his new book, Vanishing Grace: What Ever Happened to the Good News? A few of the questions we discussed made it into the November issue of CT Magazine (A Church for Outsiders), but today I get to offer you another sliver of our conversation. I highly recommend this very readable and gently challenging book, and I'm so glad to share with you Yancey's thoughts about love, suffering and the people sowing grace within our culture:

I was so struck by the place where you wrote, “I’ve never asked someone to describe a Christian and have them use the word ‘love’ .” If I were to poll my friends, I don’t think that would come out first. But wouldn’t that be wonderful if love were the opening impression.

I love the translation that Eugene Peterson uses in 1 Peter. We usually hear it as love covers a multitude of sins but he wrote it as love makes up for practically anything. Love makes up for practically anything. We know that truth in our families and in our close relationships. If only we could practice that on a broader scale so that the culture would say, "these Christians are weird. They think a lot of things we disagree with, but they love."

You describe the decline of trust in American evangelicals over the past two decades, and you diagnose this problem as a lack of grace being extended and practiced by individual Christians and churches. What forces do you think have contributed most to this change—both in the practice of Christians and in the perception of them by our culture?

The verse used as my epigraph for Vanishing Grace is from Hebrews 12: See to it that no one misses the grace of God. That’s something we can all do. It should be our motto.

There are all sorts of other Christians--progressive evangelicals, Hutterites, Mennonites-- but the perception that the media give is of angry right wing Christians. Also, in academics—you go to universities and you hear exaggerated accounts of the Crusades, the inquisition, and very little about the church’s contributions to health care, education, care for orphans, the abolition of slavery.

So I think a lot of it is distortion because it’s a secularized society.

But if you had to choose one issue that has affected younger Millenials more than any other it would be the anti-gay issue. It’s an important moral issue, but what comes across is intolerance and hatred.

You mention pilgrims, activists, and artists as three types of Christians who can still attract others to the faith. What is it about these three types that remains attractive to a post Christian Western culture?

Beginning with the activists, we need to live out our faith like the line from Francis of Assisi: “Preach at all times and when necessary, use words.” When people show a different way of being human without responding with revenge and retaliation, like Martin Luther King, or Ghandi it causes the world to stop and consider maybe there is another way. An activist follows Jesus and reaches out toward the vulnerable: the prison fellowships, the sexual trafficking, rebuilding houses after hurricanes and the tsunami in Japan.

And when asked, Why are you doing this? We can respond, because God loves you. No matter how society treats you, you are still made in the image of God and we’re going to treat you that way.

The Pilgrim is simply a style. Coming across as “I’m right and you’re wrong” is not an effective way of communicating. So a pilgrim says we are all just stumbling along, I’ve made some wrong choices, took some detours, fell down a few times, got lost, but I know my destination. I’m just going to keep walking. I’m not going to give up, but I do know the destination. The recovery movement is a beautiful example. It’s based on leading with weakness. That’s what the church is supposed to do, to dust people off and get them back on the road.

The Artist is effective because it communicates in a different level. In the book, I briefly tell the story of a play I saw in London. It was amazing because it was straight Gospel. They’re using the words from the Bible to this sophisticated erudite London crowd. At the end they’re all standing on their chairs waving handkerchiefs and shouting Bravo! Bravo! The power of the story is presented in a way that just brings joy and hope and resurrection. That’s what art does. People still read T.S.Eliot, Mary Oliver, Emily Dickinson because it has a timeless subterranean quality that a sermon would never have.

Suffering and pain comes up throughout this book. What do you think grace and Christianity have to offer in the face of pain that a secular world-view does not?

When I first got the invitation to come to Newtown [the town of the Sandy Hook school shooting in 2012], I knew I had to accept it but it was just a terrifying thing. We don’t have children. What could I possibly say standing in front of these people who’ve gone through this most horrific tragedy? What could I say to the parents or the first responders?

At the time, I happened to be doing an article that involved a lot of new atheists. I’d just been reading Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins, and Sam Harris. They have a consistently bleak picture of the universe as a random pitiless place of indifference. We are an accident never to be repeated. We’re like a match that flares out never to flare again. I noticed the New York Times was calling on pastors and priests and rabbis. The atheists were strangely silent. I’m not trying to set up a polarity. But if I were they, and I were called upon with their world-view, what could I say to the people in Newtown? It just doesn’t help to say, "we live in a universe of random, pitiless indifference." Nobody was indifferent. We were passionate. We were touched.

It didn’t seem like “oh well people die get over it.” It seemed like these were precious little children taken too soon. There has got to be something else. Not everybody believes what we believe, but we do have a word of comfort and hope to offer at such a time. I could stand before them and say God is on the side of the sufferer. No matter what people tell you. It’s not God up there sticking pins in people. God is on the side of the sufferer because God gave us grace, the grace of Jesus. See how Jesus handled children or a widow who lost her only son. That’s what God feels like right now. You’re grieved, God is more grieved. You’re upset by the violence on this planet, God is more upset.

But that’s not all. Our whole faith rest upon resurrection and among the last thing Jesus said was I’m going to prepare a place for you. Every Christian I know would say—we know where those children are. They are in that safe place. They are in the loving arms of God. That’s a word of comfort and hope that we can offer.

Support our work. Subscribe to CT and get one year free.

Recent Posts

"These Christians Are Weird . . . But They Love"

"These Christians Are Weird . . . But They Love"

"These Christians Are Weird . . . But They Love"

"These Christians Are Weird . . . But They Love"