I read Rob Moll’s newest book, What Your Body Knows About God with interest and wonder. It’s filled with fascinating tidbits of information about our bodies and spirituality, and Rob writes in a way that easily connects data points to stories. The book as a whole stands as an encouraging reminder that scientific data about the chemical composition of our bodies and brains can aid and serve our worship of God and our service to one another. I’m thankful that Rob was willing to talk with me here about What Your Body Knows About God:

I love the way your research often refers to children. What did you learn about kids and spirituality that surprised you?

Faith comes naturally and normally for children. Certain assumptions about the world and its creator seem to arise intuitively at an early age. For example, children tend to believe in spiritual beings without any trouble, and they distinguish between fairy tales and God in sophisticated ways. They believe the world was made for a purpose and by something greater than human beings. Essentially we have the beginnings of theology in some way hardwired.

Children also can directly experience God from a very young age. Our approach to children in church is often to teach them things about God, giving them a framework for when they’re older. That’s good, but children are quite capable of profound spiritual connections to God. Thanks to my parents, that was my own experience. Now as a parent, I’ve found that teaching my kids to pray—and praying with them—can be really meaningful to us both.

I think it’s easy for Christians to feel somewhat threatened by neuroscience and data that indicates our emotions and spiritual experiences can be explained through chemicals. But you write about these physical realities as indications of God’s presence at work in our bodies. Can you talk about the connection you see between the physical and the spiritual and give an example of how this connection enhanced your own spiritual practice?

Studying science it actually similar to studying Scripture. A textual critic might find Paul’s personality in his letters or the cultural assumptions of the time and place in which, say, the book of Isaiah was written. And yet, it is “God-breathed,” a reality that we cannot measure or research but must experience. This same dimension of trust exists when we study science as well. We will never put someone inside a machine and discover God. By studying the universe we won’t pinpoint the God who created it and exists beyond it. At the same time, God is present and evident in creation. I don’t see any conflict between science and faith but instead a great congruence. As we engage both, we reflect on the material world with the eyes of faith.

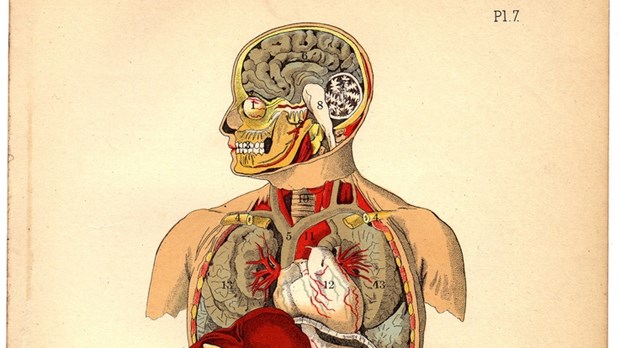

What we see in Scripture when it comes to our physical bodies is that we’re designed to connect with God and to live as the Bible teaches. And we can see these connections in fascinating ways. For example, John writes, “There is no fear in love. But perfect love drives out fear” (1 John 4:18). Science tells us that in our brain, love is this complex, higher level emotion that turns outward from ourselves. But the area of the brain involved in fear, the amygdala, tends to shut down higher-level thinking, including love. When we are fearful or angry or harboring hate, we cannot love—neurologically speaking.

You write about both the wonder of our physical bodies and also about the destruction that can happen in our bodies and souls when our brain chemistry is altered even in small amounts. How do you understand the relationship between evil and our bodies?

Paul writes in Romans, “the whole creation has been groaning … as we wait eagerly for our adoption to sonship, the redemption of our bodies” (Romans 8:22-23). Our bodies, as part of creation, are eagerly awaiting God’s new creation because they suffer from the brokenness of our world. Just as we get cancer, suffer from Parkinson’s, or deal with high blood pressure, our brains also fail to work properly.

This is hard, because when our brains don’t work right this malfunction affects us at the level of our identity. You can “battle” cancer, but how do you battle your thoughts and your pattern of thinking? How do you battle your sense of reality?

As Christians, we don’t have an answer to suffering, but instead we have a response to suffering. Christ suffered on the cross, so we have a God who suffers with us. And as we have experienced suffering, we can share in others’ suffering.

How did your research affect your own spiritual practices?

Prayer is essential to our spiritual lives, deep, concentrative prayer. I don’t mean rattling off lists of requests. I mean focusing on God. To see sustained changes in the brain, we must spend about 12 minutes of prayer daily for a few weeks; that’s the minimum. Prayer does make us more compassionate, more giving, more socially aware; but for it to do so, we need to give it time.

My research made prayer a regular part of my life in a way it hadn’t been before. I started by finding time at lunch to pray for 15 minutes. Now, as I described in the book, I pray while putting my kids to bed. Sometimes we pray together. Sometimes they hear me whispering, and they know I’m praying. I think that time has changed me. I can think of specific situations now where I think I’ve acted more compassionately when I might have instead acted angrily. I hope that’s true; and if so, I think that the way God changes us through prayer is a reason why.

As Christians, of course, we don’t believe in God in the abstract but God in the flesh in the person of Jesus. Did your research lead you to any deeper understanding of Jesus and of the incarnation?

The human body is an extraordinary creation of God, yet Scripture also tells us how ordinary it is, made of simple dust. We live this paradox, that we are both dust and imago Dei. How much more was Jesus, the incarnated God. I wonder if any of us, if we had been able to meet Jesus, would have thought that he was God. God was so fully incarnated that we might have scoffed at him or walked by without a second glance.

In this season of Advent, as we prepare to engage with the story of the Incarnation, we remember that God works not only in sweeping miraculous ways, but also in our bodies through the DNA, cells, and biological structures that he’s created. It may be hard to look at a part of our make up and say, “Oh, that part’s God.” Yet even the seemingly mundane functions of the body can evoke wonder when we consider them in light of the Creator. In incarnation, the ordinary and the extraordinary are woven seamlessly together. This is true of the person of Jesus; it’s true of us as well.

Rob Moll is an award-winning journalist and editor-at-large with Christianity Today. He has written extensively on health and health-care issues, investing and personal finance, and religion. His work has appeared in the Wall Street Journal, Books & Culture and Leadership. He has worked as a hospice volunteer. Rob serves World Vision as communications officer to the president.

Support our work. Subscribe to CT and get one year free.

Recent Posts

The Great Congruence of Science and Faith

The Great Congruence of Science and Faith

The Great Congruence of Science and Faith

The Great Congruence of Science and Faith