Today we picture the Hawaiian Islands as a premier tropical vacation destination. Nearly 200 years ago, that same idyllic island landscape boasted a revival, out of which grew the largest Protestant congregation in the world of that time.

Before 1820, the Hawaiian Islands had never encountered widespread Christianity. But that was about to change. As the Second Great Awakening traveled around the United States, it also spread outside its borders, sparking the New England missionary companies that arrived in the Sandwich Islands, which today are called Hawaii, in the 1820s and 1830s. Hiram Bingham led the inaugural mission’s team that arrived in 1820. Fellow New Englander Titus Coan, who landed in Hawaii in 1834, built on the foundation that Bingham’s generation had established, his work catalyzing the Great Revival of 1836–1840. The effect of this movement proved so significant that within a generation, the ruler of Hawaii declared his kingdom a Christian nation.

A New England Upbringing

Titus Coan was born in 1801 to pious parents, into a family of seven children during at an outbreak of revivals in New England known today as the Second Great Awakening. The son of a Connecticut farmer, Coan grew up working alongside his father, before serving in the militia after the War of 1812.

Upon his return home from the military, Coan attended revival meetings led by evangelist Asahel Nettleton, who was his cousin. Coan later wrote about the experience, “I returned just in time to see 110 of my companions and neighbors stand up in the sanctuary and confess the Lord Jehovah to be their Lord and Saviour.”

After moving to Western New York to join four of his brothers, Coan took a teaching job and in 1826, met his future wife, Fidelia Church. Within a couple of years, Coan began working at his cousin’s former school. Shortly thereafter, a revival broke out on campus, with “many of my pupils hopefully born again.” This school term “was the turning point, the day of decision” for Coan; he had felt the call of God to seek direction for “where to go and what to do.”

From there, Coan’s ministry trajectory took off. In 1830, he began studying with and ministering alongside a pastor in Western New York where an “interesting work of grace was in progress.” Coan spent that summer “laboring in the revival; sometimes meeting the Rev. Charles Finney.”

In 1831, he entered the Auburn Theological Seminary in Central New York, graduated two years later, and was shortly thereafter ordained as a missionary by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. In August 1833, he boarded a ship heading for the wilds of Patagonia on an exploratory mission for the American Board.

In 1834, Coan returned and married Fidelia Church at Park Street Church, the same congregation where Hiram Bingham had wed his wife 15 years before. Like Bingham, the wedding came only several weeks before the couple departed for Hawaii. The Coans sailed with few possessions, knowing little about the islands but holding great hope for their mission.

The Hilo Church Multiplies

It took seven months for the Coans to arrive in Honolulu in June 1835. Mission families greeted them at the Honolulu wharf and escorted them a half mile mauka (inland) to the home of Hiram Bingham. “We regard these veteran toilers with a feeling of veneration,” Titus later recalled. By 1835, the Hawaiian ports of Honolulu and Lahaina served as a crossroads in the mid-Pacific, hosting a fleet of Yankee whalers. Visits by European and British merchant ships and frigates were common in an era when European powers sought to colonize the South Pacific.

The couple only briefly stayed in Honolulu before arriving in Hilo on July 21. “Hundreds of laughing natives thronged the beach, seized our hands, gave us the hearty Aloha and followed us up to the house of our good friends, Mr. and Mrs. Lyman …” Only a handful of foreign residents from the United States and elsewhere then lived there, two of them David and Sarah Lyman, who had arrived at the Hilo station in 1833. After a season teaching children at Hilo and himself being tutored in Hawaiian by a church member named Barnabas, Coan was able to preach in the native language. He and David agreed to a partnership: David would oversee the station staying in Hilo and develop a vocational school for native Hawaiian boys, while Coan would tour their district as an itinerant evangelist.

Now known as Koana, Coan embarked on a trip to spread the gospel across the island. The journey was not easy. “For many years after our arrival there were no roads, no bridges, and no horses in Hilo, and all my tours were made on foot,” Coan journaled. He often walked along narrow, winding trails, climbing up and down steep volcanic hills, crossing streams often flowing torrentially due to the rainy windward climate.

Despite the physical difficulties, Coan was encouraged by evidence of the beginnings of a spiritual awakening. “Now they rallied in masses, were eager to hear the word.” Soon houses he visited were filled to overflowing and protracted meetings went on late into the night. When he reached a settlement in Puna, a southeastern region of the Big Island, “Multitudes came out to hear the Gospel. The blind were led; the maimed, the aged and the decrepit, and many invalids were brought on the backs of their friends. There was great joy and weeping in the assembly.”

Among those also in attendance were a brother and sister. Known as the High Priest and High Priestess of the Kilauea Volcano, the couple murdered travelers passing the volcano unwilling to turn over goods. But at the service, they experienced a heart change. The priestess yielded to a “higher Power … and with her brother became a docile member of the church.”

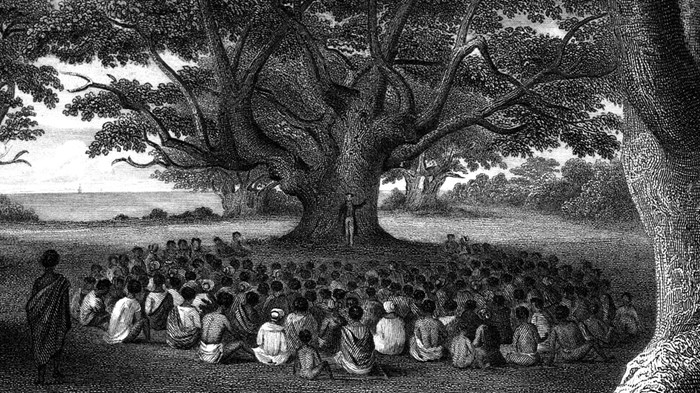

Back in Hilo, the Haili church had as few as 23 members in 1836. But it soon became a hub for the growing revival. “Soon scores and hundreds who heard the Gospel in Kau, Puna, and Hilo, came into the town to hear more. During the years of 1837 and 1838, Hilo was crowded with strangers; whole families and whole villages in the country were left, with the exception of a few of the old people.” The thatched Haili church, 200 feet long and 85 feet wide, “was crowded almost to suffocation while hundreds remained outside. … The sea of faces, all hushed except when sighs and sobs burst out here and there, was a scene to melt the heart.” Coan noted, “My precious wife, whose soul was melted with love and longings for the weeping natives, felt that no doubt it was the work of the Spirit.”

Physical manifestations added to the dramatic scene. “The word fell with power, and sometimes as the feeling deepened, the vast audience was moved and swayed like a forest in a mighty wind. The word became like the ‘fire and the hammer’ of the Almighty. … Hopeful converts were multiplied and there was great joy in the city.”

Seeing the great need for more church space, several thousand native Hawaiians, men and women, labored for three weeks and built a second thatched church, one that held a congregation of 2,000.

“But God visited the people in judgement as well as in mercy,” Titus remembered, recalling a tsunami that ravaged the Hilo church on the evening of November 7, 1837.

During evening prayers, the earth shook mightily, a sound “like the wail of doom” came forth from along the coast of Hilo. “I immediately ran down to the sea, where a scene of wild ruin was spread out before me.” A giant tsunami wave had destroyed the coastal settlement. About 200 people struggled for their lives in the tsunami wave whirlpool. Wave after wave struck. Parents called for lost ones.

“This event, falling as it did like a bolt of thunder from a clear sky, greatly impressed the people. It was as the voice of God speaking to them out of heaven, ‘Be ye also ready.’”

Despite the death toll, the tsunami seemingly sparked the revival to new levels. “Our meetings were more and more crowded, and hopeful converts were multiplied,” wrote Coan.

A native Hawaiian named Paaoao provided a first-hand account from a school in Hilo at the height of the Great Revival. In a letter published on July 4, 1838, in the Hawaiian-language newspaper Ke Kumu Hawaii, Paaoao wrote, “The Lord’s work here in Hilo is astonishing. The Holy Spirit has descended here. I have never before seen this amazing activity. … The Lord’s conversion of male and female children is marvelous.”

Soon the revival burst out of Hilo with remarkable results across the Hawaiian Islands.

Beyond the Big Island

The revival spread across the Hawaiian Islands. In Kailua, Kona Artemis Bishop reported, “Our congregation has increased to about four times its former number. About 1,000 was the former number of hearers. We have now, perhaps, about four thousand on the Sabbath morning.”

Missionary Richard Armstrong observed on Maui that “the meetings were opened as soon as I could see to read a hymn and many of them were the most solemn and interesting that I ever witnessed.”

William Alexander, at the Waioli Station on Kauai, recorded, “I have never before witnessed among the people so earnest an attention to the means of grace and so deep concern for the salvation of the soul.”

Meanwhile, back in Hilo the frenzy of the revival coalesced into the largest organized Protestant congregation in all Christendom. The son of missionaries, Sereno Bishop witnessed the Great Revival as a child. He noted, “There was a more direct and efficient presentation of Christ, less encumbered by the old and stiff Westminister forms of doctrine. This new preaching undoubtedly contributed much to the great spiritual awakening among the Hawaiians.”

Discipling New Believers

After converts embraced their new faith, Coan moved his flock into church membership with massive baptisms, keeping careful records of names and dates in a notebook.

“From my pocket list of about 3,000, 1,705 were selected to be baptized and received to the communion of the church on the first Sabbath of July, 1838.”

Coan stood in the middle of the gathering and gave the baptism blessing. “The scene was one of solemn and tender interest, surpassing anything of the kind I had ever witnessed. … All was hushed except sobs and breathing.” Communion was then distributed.

The records of the Haili church preserve the numbers received each year. From 639 in the spring of 1838, the number rose 5,244 in 1839, and 1,499 in 1840.

The confession of faith included abstinence from liquor, kawa drinking, and smoking. Coan kept track of young men who shipped out on whale ships and ministered to them upon their return. His travels included follow-up visits to villagers who returned home from Hilo.

The revivals sparked the earliest missionaries to Hawaii to acknowledge how God was working in their junior counterparts. Hiram Bingham wrote in 1839: “The Spirit of God is showered down upon the whole extent of the Sandwich Islands and those of us who have seemed to think the Gospel could hardly gain a lodgment in the heart of this people because of the alleged stupidity, or ignorance, or want of conscience, are now constrained to admit that they can be as readily affected by the Spirit of God as any class of men with whom we have been acquainted.”

In 1840, Kamehameha III (Kauikeaouli) declared his kingdom a Christian nation. The Hawaiian Constitution of 1840 began: “God hath made of one blood all nations of men to dwell on the earth, in unity and blessedness. God has also bestowed certain rights alike on all men and all chiefs, and all people of all lands.” Yet as the revival peaked that same year, the leadership of the movement experienced a time of transition. Bingham began to plan his departure from Hawaii, and Coan began confronting the challenges such mass Christian movements face as they mature.

Beginning of the End

During the Great Revival, a single foreign frigate had the power to threaten the takeover of Kamehameha III’s kingdom and a single foreign merchant ship could spread a plague. In July 1839, a French warship arrived near Honolulu and its captain demanded that Kamehameha III grant equal religious rights for Catholics. The king acquiesced, a decision which resulted in the spread of previously banned Roman Catholic churches, and the departure of strict revival-influenced temperance laws that had banned the importation of French wines and brandies.

Protestant norms were further challenged when the United States Exploring Expedition ship Vincennes sailed into Hilo Bay and began to research the Kilauea Volcano and the Hawaii Island’s peaks. Scientists began hiring native Hawaiians by the hundreds to carry 50-pound loads, a job that included working on the Sabbath. A measles epidemic traced back to a California ship in Hilo Bay spread the disease to all islands, launching widespread breakouts of diarrhea and influenza, killing about 10,000 native Hawaiians.

But even as the revival ebbed, the movement had accomplished the goal of the pioneer Sandwich Islands Mission, as charged by the American Board at the Park Street Church in Boston in 1819: “You are to open your hearts wide and set your marks high. You are to aim at nothing short of covering these islands with fruitful fields, and pleasant dwellings and schools and churches, and of raising up a whole people to an elevated state of Christian civilization.”

The ministry and life of Titus Coan in Hawaii continued to flourish following the Great Revival. Coan directed the construction of the present Haili Church from 1855 to 1859. When Fidelia died in Hilo in 1872, Titus remarried to Lydia Bingham, the daughter of Hiram Bingham, despite a 33-year difference in their ages. He died at the age of 81 in Hilo in 1882. Beyond his evangelistic accomplishments, Coan was noted in the scientific world as a pioneer volcanologist, known as the “bishop of Kilauea,” who studied activity at the Kilauea Crater and the high peaks of Hawaii Island.

The Great Revival today is recognized as a vital step in helping the native Hawaiian people survive the great decline of their numbers in the 19th century. Deborah Liikapeka Lee led her family in returning the remains of her ancestor Opukahaia (Henry Obookiah) from New England, the first notable native Hawaiian Christian. She sees the Great Revival as a key event in spreading literacy across the Hawaiian Islands, thus preparing her people for great changes ahead that threatened their future existence:

The Great Revival was very important to all Hawaiians of that time because through the growth of the churches they became educated, knowledgeable. They gained an education like Henry did. From having just an oral language they became as literate as any other people on earth.

The native Hawaiian petition against the Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 was signed in eloquent script. The people were as educated as the royal alii, their status raised by education, health and love from New England. After hundreds of years in isolation their population was diminished by introduced diseases, the remnant living today can look back at the Great Revival as a turning point in their survival.

Christopher L. Cook is the author of The Providential Life & Heritage of Henry Obookiah, and the forthcoming book Preparing the Way, a pictorial account to commemorate the bicentennial of the pioneer American mission to Hawaii sent in 1819. He is a long-time resident and author based on the island of Kauai, Hawaii.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month