We live once again, as did early 20th-century mystery writer and lay theologian Dorothy L. Sayers, in a world that could care less about the doctrines of the Christian church. And once again, many of those who care least are self-identified Christians and faithful churchgoers.

Before we lose all grip on the intellectual content of our faith, it's time to reacquaint ourselves with Sayers. In a recent Glimpses bulletin insert, I sketched her twin passions for swashbuckling drama and intellectual order, and suggested how these suited her to the great task of modern apologetics—a task probably still as urgent for Christian as for non-Christian audiences:

Dorothy L. Sayers (1893–1957) was a prolific scholar, novelist, essayist, playwright and translator. Those who know about her today have usually met her through her detective stories and their memorable hero, Lord Peter Wimsey. But there is much more to her story. In a time of spiritual confusion, she emerged, almost despite herself, as an unlikely voice of clarity and a compelling lay "preacher" of the gospel.

Sayers, a clergyman's daughter, was born into a late-Victorian Oxford, England that had ceased to be a sleepy medieval town: automobile factories now encroached on its narrow streets and dreamlike spires. Worse, the Christian tradition that had birthed Oxford University was now in full retreat throughout Europe. Anyone truly "modern" believed that humans, like everything else, are just aggregations of atoms, and matters of morality and spirit thus mere illusions.

Even the Church of England was giving in, so that by the turn of the century, bishops who doubted Christ's resurrection were called "courageous." And though many ministers and laypeople still held on to Christian faith, it was increasingly a sentimentalized, moralistic version.

In late girlhood and adolescence, Sayers was bright enough to observe and dislike the stuffed-shirt piety of the modernizing Church of England. She remarked that, like sex, such mysteries of the faith as the sacraments and God himself seemed to be considered "exceedingly sacred and beautiful," yet also "indelicate, and only to be mentioned in whispers." As she would later say about this sort of overdone churchiness: "At the name of Jesus, every voice goes plummy."

She was saved from outright rebellion against her father's faith by reading the Roman Catholic journalist-apologist G. K. Chesterton—especially his Orthodoxy. "It was stimulating to be told," she wrote, "that Christianity was not a dull thing but a gay thing; not a stick-in-the-mud thing but an adventurous thing; not an unintelligent thing but a wise thing, indeed a shrewd thing."

Pressing in to find the truth, she discovered a God who is "a fact, a thing like a tiger, a reason for changing one's conduct." A fan of Dumas's The Three Musketeers, she had swooped about her girlhood home in the costume of D'Artagnan. Now she began to see just how dramatic and compelling is the gospel story.

After an Oxford education in medieval languages (she was in the first class of women to receive their B.A. and M.A.), Sayers worked first as a copy editor, then an advertising writer. Then she began writing a well-crafted series of mystery novels featuring the aristocratic detective Lord Peter Wimsey.

In the late 1930s and the 1940s, however, her life changed direction when she was invited to write a series of plays for performance in the Canterbury Cathedral. Here was an opportunity to reconnect with all the drama and pageantry she had loved as a girl in The Three Musketeers. Her plays made Christian themes vivid and launched her into a new career as a lay theologian, as newspapers and institutions began clamoring for her thoughts on the faith.

She threw herself into that role in a way that was both swashbuckling and intellectually rigorous. During the season of Lent in 1938, Sayers wrote an article for the London Times in Chestertonian mode: "Official Christianity . . . has been having what is known as a bad press. We are constantly assured that the churches are empty because preachers insist too much upon doctrine. . . . The fact is the precise opposite. . . . The Christian faith is the most exciting drama that ever staggered the imagination of man . . . and the dogma is the drama."

She followed with "What Do We Believe?" "The Other Six Deadly Sins," "The Triumph of Easter," and many other essays. She wanted to awaken a sleeping church and insist that it reclaim the doctrines of the historic creeds—powerful realities that had been lost under layer upon layer of well-meaning but stuffy "clergy jargon."

In 1940, as her reputation as a public apologist grew, she was asked by the BBC to write a serialized play on the life of Jesus. At the time (and up until 1968), it was illegal in England to portray Jesus on stage, and it required a special church dispensation even to allow this radio play. She wrote, "I feel very strongly that the prohibition against representing Our Lord directly on the stage or in films . . . tends to produce a sense of unreality which is very damaging to the ordinary man's conception of Christianity. . . . ‘Bible characters' are felt to be quite different from ordinary human beings."

Her way of breaking through this sense of unreality was to write a new translation from the Greek that avoided the churchy verbiage of the good old "Authorized Version" (KJV). She directed her actors to speak with accents appropriate to the working-class status of the disciples. When the public heard The Man Born to Be King, "rapturous letters poured in from listeners of all ages." People were grateful that Sayers had presented the story of Jesus in a realer and more powerful way than they had ever heard. C. S. Lewis was among those who loved the play: for the rest of his life, he read it each year during Holy Week.

Sayers's final and arguably greatest work began when she was 51, huddled in a bomb shelter, reading her grandmother's copy of Dante's Inferno. For the rest of her life, she labored to make Dante's epic poem of Christian theology, spirituality, and morality live again for a new generation.

On December 17, 1957, Dorothy L. Sayers died of heart failure. She was sixty-four years old.

Bishops, dignitaries and many friends attended the memorial service. There, a eulogy by C. S. Lewis was read and leather-bound copies of her essay "The Greatest Drama Ever Staged" were handed out to all. Then as now, Dorothy L. Sayers was recognized as one of England's most remarkable voices for the truth of faith.

* * *

"The Dogma is the Drama," Dorothy L. Sayers—excerpts

It is . . . startling to discover how many people . . . heartily dislike and despise Christianity without having the faintest notion what it is. If you tell them, they cannot believe you. I do not mean that they cannot believe the doctrine: that would be understandable enough, since it takes some believing. I mean that they simply cannot believe that anything so interesting, so exciting and so dramatic can be the orthodox Creed of the Church.

+++

Somehow or other, and with the best intentions, we have shown the world the typical Christian in the likeness of a crashing and rather ill-natured bore—and this in the Name of One Who assuredly never bored a soul in those thirty-three years during which He passed through the world like a flame.

+++

It is the dogma that is the drama–not beautiful phrases, nor comforting sentiments, nor vague aspirations to loving-kindness and uplift, nor the promise of something nice after death–but the terrifying assertion that the same God Who made the world lived in the world and passed through the grave and gate of death. Show that to the heathen, and they may not believe it; but at least they may realise that here is something that a man might be glad to believe.

* * *

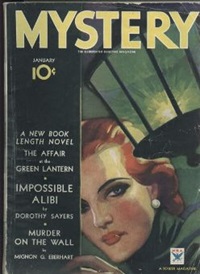

The January 1934 edition of Mystery featured a short story by Dorothy Sayers titled "Impossible Alibi." Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month