"Nowadays we think we are too smart to believe in the Virgin birth of Jesus and too well educated to believe in the Resurrection. That's why people are going to the devil in multitudes."

"Center fielder Billy Sunday made a three-base hit at Farwell Hall last night. There is no other way to express the success of his first appearance as an evangelist in Chicago." So reported the local press about Sunday's first public appearance as a preacher in the late 1880s. "His audience was made up of about 500 men who didn't know much about his talents as a preacher but could remember his galloping to second base with his cap in hand."

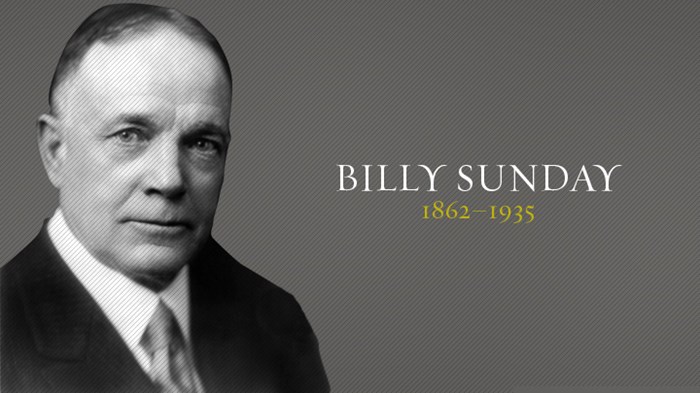

This was just the beginning for Sunday. Until Billy Graham, no American evangelist preached to so many millions, or saw as many conversions—an estimated 300,000.

From baseball to the Y

"I never saw my father," Sunday began his autobiography, for his father had died of pneumonia in the Civil War five weeks after Sunday's birth. In fact, his early childhood in an Iowa log cabin was enveloped by death—ten deaths before he reached the age of 10. His mother was so impoverished, she sent her children away to the Soldier's Orphans Home. Sunday survived only with the support of his brother and his love of sports, especially baseball.

His professional baseball career began with the Chicago White Stockings in 1883 (he struck out his first 13 at bats); he moved to the Pittsburgh Pirates, and in 1890, to the Philadelphia Athletics, where he was batting .261 and had stolen 84 bases when he quit.

Timeline |

|

|

1855 |

D.L. Moody converted |

|

1859 |

Darwin publishes Origin of Species |

|

1860 |

U.S. Civil War begins |

|

1862 |

Billy Sunday born |

|

1935 |

Billy Sunday dies |

|

1941 |

Bultmann calls for demythologization |

Ever since his conversion to Christianity at the Pacific Garden Mission in Chicago in 1886, he had felt an increasingly strong call to preach. The YMCA finally convinced him to leave baseball to preach at their services (which meant a two-thirds cut in pay). He moved on to work with two other traveling evangelists, then was invited to conduct a revival in Garner, Iowa. From then on he was never without an invitation to preach, at first holding campaigns in midwestern towns and then, after World War I, preaching in Boston, New York, and other major cities.

Much of his success was due to his wife, Helen Amelia Thompson. She organized the campaigns and did much of the advance work. She even tried to better Billy's vocabulary in her letters to him, deliberately including words he would have to look up.

Prancing and cavorting

Sunday's preaching style was as unorthodox as the day allowed. His vocabulary was so rough (e.g., "I don't believe your own bastard theory of evolution, either; I believe it's pure jackass nonsense"), Christian leaders cringed, and they often publicly criticized him. But Sunday didn't care: "I want to preach the gospel so plainly," he said, "that men can come from the factories and not have to bring a dictionary."

Sunday was master of the one-liner, which he would use to clinch his practical, illustration-filled sermons. One of his most famous: "Going to church doesn't make you a Christian any more than going to a garage makes you an automobile."

He used his whole body in his sermons (and other nearby objects, such as his chair, which he would sometimes fling around while preaching). As one newspaper wrote, "Sunday was a whirling dervish that pranced and cavorted and strode and bounded and pounded all over his platform and left them thrilled and bewildered as they have never been before."

He concluded his sermons by inviting people to "walk the sawdust trail" to the front of the tabernacle to indicate their decision for Christ.

Unusual for American evangelists, Sunday also addressed social issues of the day. He supported women's suffrage, called for an end to child labor, and included blacks in his revivals, even when he toured the deep South. This made him enemies, as did his support of Roman Catholics (whom he considered fellow Christians) and Jews. On one of the hottest topics of the day, evolution, he walked a tightrope: he had no sympathy for evolution, but neither did he warm up to Genesis literalists.

However he was never a friend of liberals: "Nowadays we think we are too smart to believe in the Virgin birth of Jesus and too well educated to believe in the Resurrection. That's why people are going to the devil in multitudes."

And he firmly stood against card playing, movie going, and Roaring '20s fashions. "It's a damnable insult some of the rigs a lot of fool women are wearing up and down our streets," he said. His favorite vice was "Mr. Booze." In fact, his preaching was instrumental in getting Prohibition passed. "To know what the devil will do, find out what the saloon is doing," he said repeatedly. "If ever there was a jubilee in hell it was when lager beer was invented."

After World War I (which he raised millions of dollars to support), Sunday's influence decreased. Radio, movies, and other entertainments drew masses away from the preacher, though he never lacked for speaking engagements.

"I'm against sin," he once said. "I'll kick it as long as I have a foot. I'll fight it as long as I have a fist. I'll butt it as long as I have a head. I'll bite it as long as I've got a tooth. And when I'm old and fistless and footless and toothless, I'll gum it till I go home to Glory and it goes home to perdition."

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month