The Powerful Legacy of Paul Farmer and What He Can Teach Us

Every sport has its magically gifted superstars. They’re light years beyond what most of us will ever do in pickup basketball or the local soccer league. We just barely play the same game as them, but because we do they inspire us to practice harder and try things we wouldn’t have otherwise. Go to any local game, and you’ll see players taking three-pointers they wouldn’t have ten years ago (and often making them) thanks to Steph Curry.

Dr. Paul Farmer died this week at age 62. He was a global health champion, Harvard Medical School professor, anthropologist, cofounder of the nonprofit Partners in Health, and author. He spoke of being motivated and deeply informed by theology. The humanitarian world just lost a Steph Curry.

I didn’t know Farmer. We talked once for five minutes at a book festival where we were both speaking. Him, rightly, to a much larger audience. Over the years in Haiti, I would regularly be asked by a friend or neighbor to contribute to transportation costs because they couldn’t find needed medical care locally. They would travel to the Zanmi Lasante hospital that Paul Farmer established in the Central Plateau to find treatment they needed–and also deserved.

Since the news of Farmer’s death, I’ve felt a strange kind of sadness–frustration and a melancholic gratitude.

The people Farmer served (HIV patients in Haiti, TB patients in Russian prisons, and many more) deserved an unrelenting genius on their side. It’s a blow to lose an advocate like him. I’m deeply frustrated–with a Psalm–94-like anger that cardiac events rain down on the just and unjust alike–because someone who helped with Farmer’s depth and breadth is gone, when he could have helped so many people for many more years. I’m also grateful that he did so much that his loss is monumental.

I first learned of Farmer from a New Yorker profile, published in 2000, that later expanded into the book Mountains Beyond Mountains. For a number of years, I kept the original pages from the New Yorker, torn out, wrinkled, and stapled in the top left corner, copying and sharing them with people who wondered why my wife and I were moving or had moved there. (When my first book came out, I sometimes joked it was the story of what it was like to live and work in Haiti when you weren’t a genius.)

With his death, a few specific scenes and passages came back to me. Like Steph Curry, I think Farmer helped push many of us to see the game differently, to not settle for the easy basket, when it comes to understanding the work and ethics of serving people in poverty.

Breaking the Rules for Good

As a medical student, Farmer was traveling to Haiti regularly and experiencing the vast back-and-forth disparity. He studied how to bootstrap the clinic they were setting up in Cange, but then decided to not settle. Instead, “The first microscope in Cange was a real one, which he stole from Harvard Medical School. ‘Redistributive justice,’ he’d later say. ‘We were just helping them not go to hell.’”

A Robin Hood tale is inherently satisfying. But why in this case? It’s an origin story of being committed to delivering quality care. Also, in our time that incentivizes turning even minor grievances into outrage wildfires, Farmer reminds us to be morally serious–that echoes through all his work–about love for neighbor, about God’s justice and heart for the poor, and about being people who act. (Not giving blanket permission for theft, but I’m also not saying that justice isn’t sometimes mischievous.)

Farmer wasn’t okay with using the just-barely-good-enough, the out-of-date technology, the leftovers, for which people who were vulnerable should presumably be grateful that they got anything at all. Farmer worked to change this kind of thinking and practice. This is still a problem today that can infect how we think about working with people in poverty, whether in the U.S. or other countries.

He took as a radical and serious moral (and as we’ll see below, theological) starting point: Poor rural Haitians unequivocally deserved the same care as people in Boston.

He was right.

The System and the Theology

The New York Times obituary of Farmer said, “He was a practitioner of ‘social medicine,’ arguing there was no point in treating patients for diseases only to send them back into the desperate circumstances that contributed to them in the first place. Illness, he said, has social roots and must be addressed through social structures.”

They should have also noted that he came to this understanding–and then helped to influence the approach of global health–through theologians.

He co-wrote In the Company of the Poor with theologian Gustavo Gutierrez. In the first chapter he talks about the preferential option for the poor and about how theology helped him in his work:

And it was the patient, scholarly work of Gustavo Gutiérrez that helped me make sense of the poverty I saw around me in Haiti, elsewhere in Latin America, and back home in the United States. Understanding poverty as “structured evil,” and understanding how it is perpetuated, is not the same as fighting it. But if we believe that knowledge can inform practice—if we believe in pragmatic solidarity as the best confirmation of theory—then it is best to have intellectual accompaniment [like Gutiérrez]. (In the Company of the Poor)

Poverty is a systemic issue. Theology helps us to understand sinful systems. Practitioners who want to change the system do well to learn from theology. Farmer demonstrated how to do this well.

Challenge the Status Quo and “Sustainability”

Tracy Kidder, author of the New Yorker profile, went hiking through rural paths with Farmer for five hours to find a young man who had missed a dose of his TB medication. Farmer wanted to be sure his cure wasn’t interrupted.

We started back. I [the author] slipped and slid down the paths behind Farmer. “Some people would argue this wasn’t worth a five-hour walk,” he said over his shoulder. “But you can never invest too much in making sure this stuff works.”

“Sure,” I said. “But some people would ask, ‘How can you expect others to replicate what you’re doing here?’ What would be your answer to that?”

He turned back and, smiling sweetly, said, “F--- you.”

Then, in a stentorian voice, he corrected himself: “No. I would say, ‘The objective is to inculcate in the doctors and nurses the spirit to dedicate themselves to the patients, and especially to having an outcome-oriented view of TB.’” He was grinning, his face alight. He looked very young just then. “In other words, ‘F--- you.’”

Over the years I’ve thought of this scene when I’ve been tempted to, or have actually succumbed to, my excuses to not climb over the next mountain and then the next. I’ve thought of this when sustainability is used as an excuse. I’ve told other people this story occasionally. (I just looked it up and fortunately remembered it pretty accurately for the past two decades.) I will keep telling myself this story.

There are other notes I’ve taken from Farmer that have sharpened my thinking: Be outcome oriented. Don’t settle. Don’t use the idea of sustainability, or lack thereof, as an excuse for not providing the best possible intervention. Don’t let faith or charity or missions cloak our condescension or our acceptance of the unjust way things are. Care. Do the work.

He showed that this work takes five-hour hikes as well as personal relationships, learning the language, an intellectual commitment to understanding the issues deeply, and finding and refining the best practices:

Poverty is not some accident of nature but the result of historically given and economically driven forces. Human beings constitute the social world, and we will always shape it.

Understanding poverty and inequality requires multiple disciplines: economics, ethics, law, sociology, anthropology, epidemiology, and so forth. Most of all, it requires listening to those most affected by poverty, which is to say the poor and otherwise marginalized. Listening is also a significant part of accompaniment. Listening is thus both engagement and research. (In the Company of the Poor)

As brilliant and accomplished as he was, his learning, listening, and work modeled a humble approach–that was willing to keep hiking.

***

I’m sure Farmer wasn’t perfect. He must have critics and failed projects. And I’m not trying to summarize A Paul Farmer Approach. I’m just sharing a few highlights that have encouraged and stayed with me, as my tribute to him. They’re a few of the reasons I’m grateful for Farmer and why I’m sad.

And what I can do in my sadness, like looking at how Steph Curry plays and has changed the game, is get up tomorrow to keep practicing, practicing, practicing. Maybe you want to as well. This is our faithful response to God’s grace: to practice (and keep practicing) participation in God’s slow kingdom coming. As we follow after Jesus, we get to follow after people like Farmer who help us find the way toward loving well.

With condolences to family, friends, colleagues, and patients who have been or would have been under his care, I’ll close with the last paragraph of Farmer’s first chapter in his book with Gutiérrez. Where he had written Gutiérrez’s name, I’ll replace it with his. I love how he highlighted the need for accompaniment that he found in someone else, because many of us then found the same in him:

As long as poverty and inequality persist, as long as people are wounded and imprisoned and despised, we humans will need accompaniment—practical, spiritual, intellectual. It is for this reason, and for many others, that I am grateful for [Paul Farmer’s] presence on this wounded but beautiful earth.

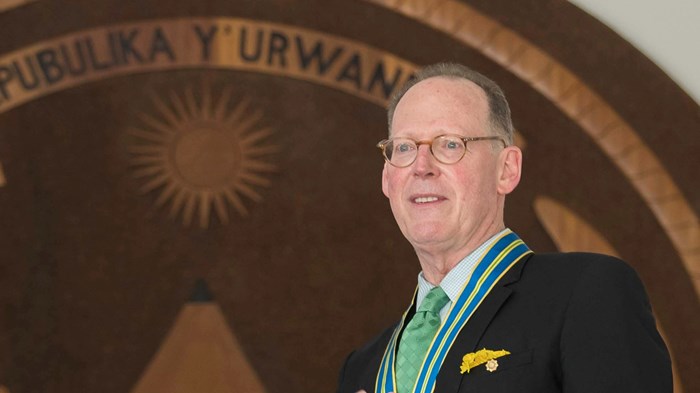

Kent Annan is director of Humanitarian and Disaster Leadership at Wheaton College, where he leads an M.A. program as part of the Humanitarian Disaster Institute.

The Better Samaritan is a part of CT's

Blog Forum. Support the work of CT.

Subscribe and get one year free.

The views of the blogger do not necessarily reflect those of Christianity Today.