We are not our own

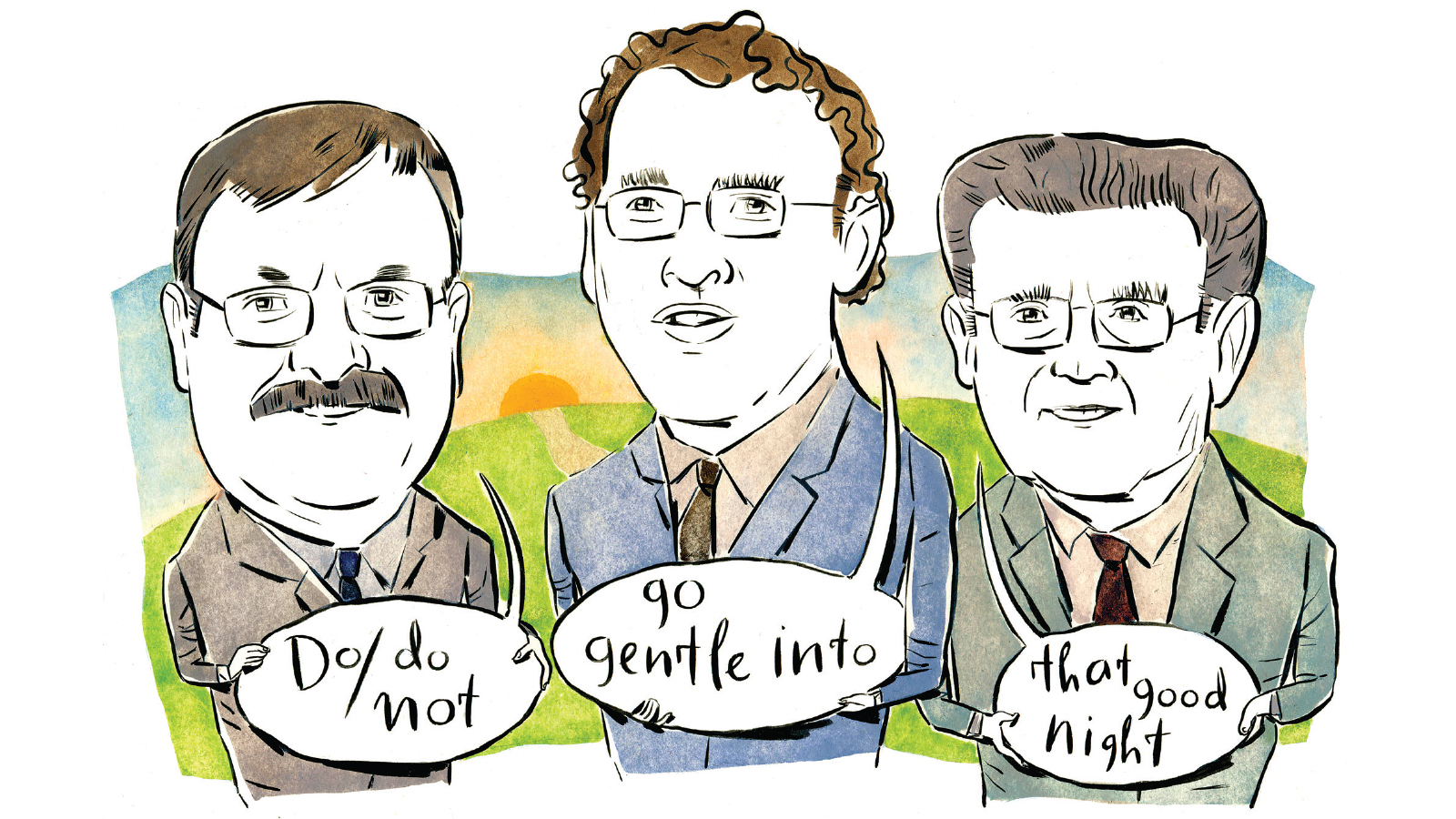

Dennis Sullivan, a physician and bioethicist, is director of the Center for Bioethics at Cedarville University in Ohio. He comments on bioethical news at BioEthics.com.

Brian Green had been the pastor of a small Baptist church for 12 years. He and his wife, Judy, were looking forward to their first grandchild. Then came the sudden news: Judy had stage four ovarian cancer. The prognosis was poor, but exploratory surgery and chemotherapy might extend her life by a year or more.

Judy was not interested. She rejected surgery or chemo, saying, "God is in control; I'm going to heaven."

Distraught over her decision, Brian came to me for advice. How should he respond?

From an ethics perspective, the answer was simple. Make sure that Judy did not have a treatable depression and that her decision-making capacity was intact. Ultimately, competent patients have the right to make their own decisions, including refusing treatment.

However, from a spiritual perspective, things are a bit more complex. First Corinthians 3:16-17 tells us that our bodies are God's temples and that God's Spirit dwells in us. We may not destroy God's temple, for it is sacred. The epistle later reminds us, "You are not your own; you were bought at a price" (6:19-20).

It is easy to say, "God is in control." But how does that guide us at the end of life? Paul gives a hint in his letter to the Philippians: "For to me, to live is Christ and to die is gain …. I am torn between the two: I desire to depart and be with Christ, which is better by far; but it is more necessary for you that I remain in the body. Convinced of this, I know that I will remain, and I will continue with all of you for your progress and joy in the faith" (1:21-25).

So what is the key question?

Based on Paul's example, it is not, "How can I suffer as little as possible?" A better question would be, "How can I best minister to others in my final days on this earth?" And that ministry is surely relational.

Our relational ministry at the end of life may involve addressing unfinished business with friends and loved ones. Many who are suffering from a terminal illness worry about being a "burden" to their family. For most, family members would gladly bear this burden. In fact, they may feel hurt if deprived of that right. In the last days of life, our final ministry should be one of humility—practicing vulnerability and allowing others to care for us. Ultimately, we are preparing for heaven, and we become more and more like children as we prepare to meet our heavenly Father.

I was never able to share this perspective with Brian, and I'm not sure it would have made a difference; Judy passed away just four months after her diagnosis. But his dilemma gave me new insight into the deep meaning of the phrase, "God is in control."

Death can be a witness

Rob Moll is the author of The Art of Dying: Living Fully Into the Life to Come (InterVarsity).

Several years ago, I visited Chestnut Street Baptist Church in Camden, Maine. The small congregation gathered on a Sunday evening, heard the sermon of a dual vocation pastor, and then prayed.

The church is located in a former fishing village turned vacation spot for Bostonians, and these members were local Mainers who kept it alive. The congregation's prayer requests—in addition to travel mercies and health concerns—witnessed to Christ in a largely secular community. One of those prayer requests continues to ring in my ears. It was for a man who was suffering from cancer. His decision not to pursue curative treatment had shocked his family and his friends. He, however, sought to show them where his hope lay: not in his health or his longevity but in Jesus Christ, who has defeated death.

This man had reached the point of asking himself, as did the apostle Paul in Philippians 1, whether it was better to live or die. We Christians live with the same dilemma. We know the power of the Resurrection and yearn to know it more fully. We believe, as Paul wrote in Romans 8:11, that "the Spirit of him who raised Jesus from the dead … will also give life to your mortal bodies."

Death has no power over us. While Paul preferred to remain in the body, Jesus submitted to death and so defeated it. As Christians, we should neither seek death nor flee from it.

In our death-confused culture, Christian fearlessness in the face of death is desperately needed. Dionysius was a third century bishop of Alexandria who shepherded the church through horrific persecution. He also oversaw the church's medical care during an epidemic. He later wrote in praise of the Christians' service in the face of death. He compared it to martyrdom: "Many, in nursing and curing others, transferred their death to themselves and died in their stead …. The best of our brothers lost their lives in this manner."

Such concern stood in sharp contrast to the pagans in the city: "At the first onset of the disease, they pushed the sufferers away and fled from their dearest, throwing them into the roads before they were dead and treated unburied corpses as dirt." In The Rise of Christianity: How the Obscure, Marginal Jesus Movement Became the Dominant Religious Force in the Western World in a Few Centuries, author Rodney Stark links the growth of the church to its health care service.

Today our culture seeks to avoid death through increasingly expensive medical technology. Christians like those in Camden can point to an alternate story. Death is no longer our enemy; it has already been defeated. Meeting it gracefully without needlessly prolonging life can be the best witness, for those suffering terminal illness and their family members. We believe, as the poet John Donne wrote, "One short sleep past, we wake eternally, / And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die."

Turn to the comforter

Robert Orr is professor of medical ethics at Loma Linda University and author of Medical Ethics and the Faith Factor: A Handbook for Clergy and Health Care Professionals (Eerdmans).

Sometimes the answer to this question is a clear yes or no. Other times it is not clear. When a patient declines treatment that has some potential for benefit, it is crucial to know the reason.

Your mom's painful, widespread cancer has blocked the urine outflow from her kidneys. Dialysis might postpone her death for a few days or weeks, but she declines because she feels she is no longer able to fulfill God's call in her life. It is imperative to continue to make her comfortable, but probably not necessary or helpful to interfere with her refusal.

Your son's wife has left him, and he is so depressed, he loses his job. He develops a life-threatening infection and says he doesn't want antibiotics, because as far as he can see, his life is over. You should intervene in this suicidal decision, even over his objection.

Those were easy. What if your husband has a severe stroke, leaving him paralyzed on one side, unable to speak or swallow, and he does not want a feeding tube? Many factors come into play here.

Other situations where intervention over patient refusal may be justified include when a patient feels like she is too much of a burden to others, or is overly concerned about the cost of care, or acknowledges she has unfinished business with loved ones or with God.

How does a believer look at such gray dilemmas in medical ethics? There are several biblical precepts to consider.

First, human life is sacred. Each individual, regardless of his or her ability to function, is made in the image of God.

Second, human life is finite. Since the Fall, we are exposed to suffering and subject to death. Unless Jesus returns first, we will all die. Some believe that, in life-extending decisions, to even consider quality of life issues only violates the sanctity of life. But this is not always the case. Factors such as a patient's amount of suffering, ability to interact with others, and the burdens and cost of treatment can be useful in making a difficult decision.

God has allowed us to develop technologies that can cure disease and prolong life. In addition, he has given us dominion over our lives and our resources, and we are expected to be good stewards of both.

God is sovereign and omnipotent. He doesn't require our technology if he chooses to intervene supernaturally. No matter the outcome, believers can look forward to an eternity in heaven, praising God forever.

In gray situations, not all believers will come to the same conclusion. Some will place a different priority on these biblical precepts than others. Some will choose life-prolonging medical advances, and some will not; both can be wise decisions. But all believers do have something in common. We all have access to a Comforter. We can support, counsel, and pray for each other, seeking God's wisdom, guidance, and peace.

Copyright © 2011 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Additional Christianity Today coverage of life ethics and death and dying includes:

A Christian Response to Overpopulation | We can continue to affirm life while acknowledging that unrestricted population growth can put women and children at risk. (May 25, 2011)

Carolyn Arends Contemplates Her Own Death, and Yours | Going down singing: Why we should remember that we will die. (April 18, 2011)

A Chronicle of Hopeful Dying | Death is not the enemy, says cancer-stricken Walt Wangerin, but a chance for Jesus to shine. (March 2, 2010)

Editorial: Go Gently into That Good Night | Fear of mortality lies at the root of our bioethics confusion. (January 2, 2007)

Previous "Village Green" sections have discussed marijuana morality, credit card debt, tithing during unemployment, illegal immigrants, giving to street people, the best Christmas stories, laws that ban Islamic veils, the Tea Party, Afghanistan, Bible smuggling, creation care, intelligent design, preaching, immigration, Lent, premarital abstinence, aid to foreign nations, technology, and abortion.