Sometimes it is hard to remember just how I'm connected to some of my relatives. Beyond first cousins, it can be tricky to explain (or remember) what the relationship is. One of my cousins even calls himself my "imaginary cousin." (My father's parents fostered his mother. I don't know what that makes me to him. Yet we feel related.)

My father must have had a similar difficulty remembering family connections. After his death, I found a scroll (how positively biblical!) made of 10 sheets from a yellow legal pad. On the scroll, he diagrammed the descendants of my paternal great-grandmother's nine siblings. One of those nine had a daughter who married a prominent anti-alcohol crusader. He headed up the American Temperance Society and befriended Muslim leaders who appreciated Christians who didn't drink. I knew him as Uncle Billy, but I sure don't know how to label that relationship.

Like families, the church has a genealogy. And just as my family has regional concentrations in Illinois, Wisconsin, Arizona, and Pennsylvania, so the early church had regional concentrations in Antioch, Alexandria, and Rome. Eventually, Jerusalem and Constantinople joined the list. Each center had a family history that helped the churches in their sphere know who they were and tell true believers from wayward ones.

Protestantism was, in part, an argument with Rome over the right version of the Western church's family history. The true heirs of the apostles who planted the church in Rome were those who treasured and taught true biblical faith, the Reformers taught, not necessarily those who occupied a place in a succession of officeholders.

This Western family dispute dominated, of course, because the other ancient centers of the Christian family fell to Muslim conquerors. Those other Christian communities no longer carried political clout in their urban centers.

Like families, the church has a genealogy. Protestantism was, in part, an argument with Rome over the right version of the Western church's family history.

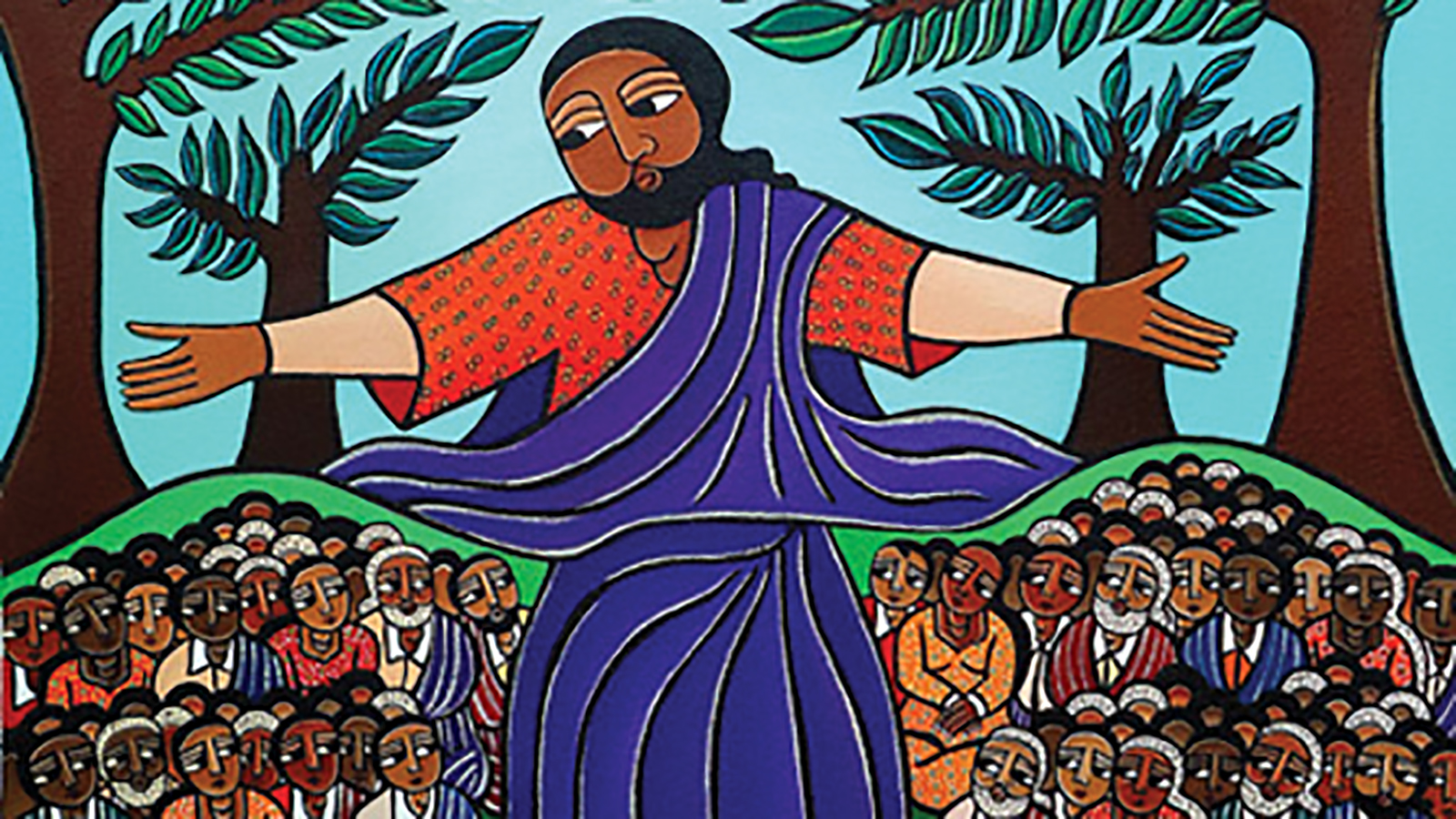

In recent decades, many Western Christians have rediscovered these communities and their family histories. This summer I read Thomas C. Oden's new book, The African Memory of Mark: Reassessing Early Church Tradition. Oden's tale centers on Alexandria, where the church produced both the early church's greatest defender of orthodoxy (Bishop Athanasius) and its most infamous heretic (Presbyter Arius).

Oden argues that we ought to take the Alexandrian church's tales of its own origins seriously, as seriously as I take my father's yellow scroll.

From various African sources, Oden reconstructs a church's memory of an African apostle, born in what is today Libya. Young John Mark's family migrated to Jerusalem, where he became one of Jesus' earliest followers and, significantly, the writer of the earliest Gospel. Mark's father was likely a cousin to Simon and Andrew, and their family home in Jerusalem became a focus of Christian activity. It was the place where the church prayed when Herod imprisoned Simon Peter. It was also likely the place where Jesus' core followers gathered to await Pentecost. John Mark became a key evangelist. His disappointing missions with Paul and Barnabas (another relative) are well known, but African Christians also remember his successful missions to his Libyan birthplace and then to Alexandria, the ancient seat of culture and learning in the region.

In 1 Peter, we find this verse: "She who is at Babylon … sends you greetings, and so does Mark, my son" (ESV). Many interpreters treat Babylon as a code word for Rome. But Babylon was also a neighborhood in Alexandria, an urban enclave for expat Jews. That is where the African memory places Peter and Mark. The African church also remembers Mark's martyrdom, battered by being dragged through Alexandria's streets by horses.

Mark didn't die before he appointed successors in Libya and Egypt, just as Paul mentored leaders to follow him in places he evangelized. Mark's first convert, a shoemaker named Anianus, succeeded him. He heads the list of bishops, beginning in A.D. 68. In this era before New Testament Scripture was canonized, knowing the spiritual "begats" of your fellowship of believers was important for validating your church's teaching. This genealogical approach to authority was never in tension with Scripture. As a matter of fact, the first authoritative list of our present New Testament books came from one of Mark's successors, Bishop Athanasius, in A.D. 367. The list originated in Alexandria, and was confirmed over the next 30 years by councils in Rome and Carthage. We have our New Testament because of the faithfulness of Mark's successors.

Engaging in dialogue with the ancient churches can remind us of those parts of our heritage—like the New Testament—that we may take for granted. And that can spur us on to be faithful in our own generation, that we might leave an inheritance to our family's next generation.

Copyright © 2011 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

The African Memory of Mark: Reassessing Early Church Tradition is available from ChristianBook.com and other book retailers.

Previous "Past Imperfect" columns by David Neff include:

Criminalizing Circumcision | We have secularized the ancient Jewish rite—but it is still inescapably religious. (August 29, 2011)

A Second-Coming Christian| The 'blessed hope' was the linchpin of my father's faith. (July 18, 2011)

Remember the Red Sea| Why not capitalize on the richness and mystery of our ancient symbols? (May 19, 2011)

Dwelling in Heaven's Suburbs| Creating a culture of resurrection is key to full-orbed ministry. (September 28, 2010)