It may have been the most civil statement ever made in thoroughly uncivil times.

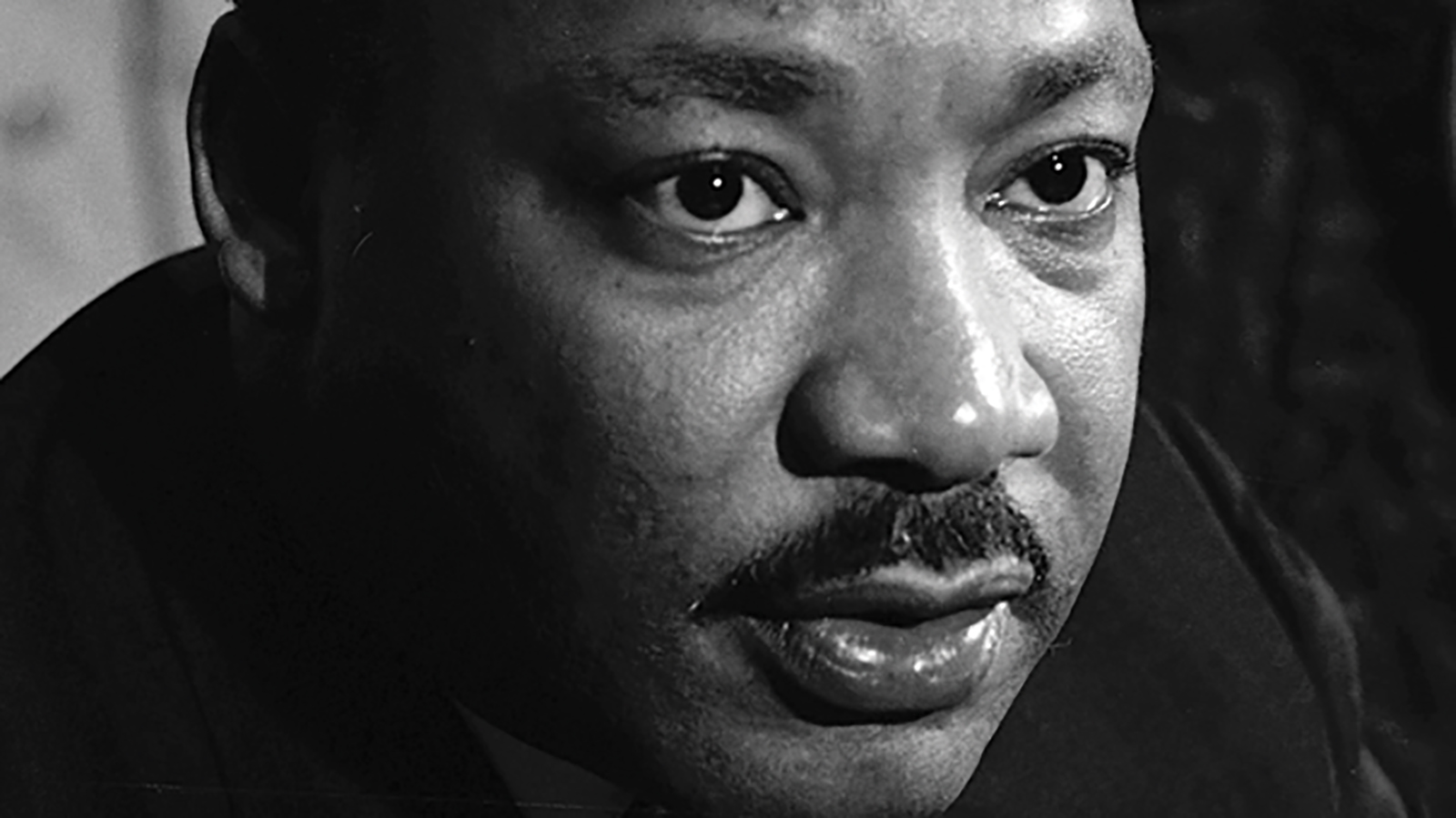

Responding to fellow clergy who criticized the civil rights protests in Birmingham, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. penned his towering, magnificent "Letter from Birmingham Jail" in 1963.

It's time that King's letter—and the spirit and tone in which it was written—be re-examined by every pundit, every pastor, every activist, and every politician who rightly bemoans the demise of civil discourse in the U.S.

If anyone had a right to unleash an uncivil, scathing, ad hominem attack on his opponents, it was King. It is hard for younger people to imagine (and getting harder for many of us older ones to remember) the conditions under which many African Americans lived throughout the South just over 40 years ago. Segregation, lynchings, African American churches and homes firebombed. Jim Crow laws even prevented "colored people" from attending the circus and playing pool with whites.

Yet civil rights leaders painfully, persistently, and peacefully protested the injustice of segregation. In doing so, they often broke segregation laws. All too often, protesters reaped a reward of fire hoses, police dogs, and incarceration.

Several Birmingham clergy admonished the protesters, urging them to work within the law. King's letter was a response to those clergy.

Put yourself in his place. Who would not be furious, even enraged, by the statement of these ministers? How was King able to respond in such a civil and well-reasoned manner? Remember that King himself was a Baptist pastor. His response reflected his deeply held Christian convictions. He quoted the words of Jesus, and appealed to the example of Paul, as well as Thomas Aquinas, Martin Luther, and John Bunyan.

Also, he did not question his opponents' motives. Instead, he called them "men of genuine good will" whose "criticisms are sincerely set forth." "I want to try to answer your statement," he wrote, "in what I hope will be patient and reasonable terms." And that he did.

Yes, King clearly cataloged the injustices faced by African Americans. He called "white moderates" to task and forcefully reminded them that justice delayed was justice denied. And most famously, citing Augustine, he claimed that "an unjust law is no law at all."

But King never engaged in name calling or personal attacks. Without distortion, he patiently and fairly acknowledged his opponents' positions—and then dismantled them.

King had reason, justice, facts, and conviction on his side—as well as the gospel. He did not need vitriol, and he did not employ it.

King had reason, justice, facts, and conviction on his side—as well as the gospel. He did not need vitriol.

Contrast that with what we see and hear daily. The fast food chain Chick-fil-A provided sandwiches to a conference on traditional marriage, and, according to The New York Times, a college newspaper ran the headline, "If you eat Chick-fil-A, you're anti-gay." Gay groups boycott the chain. One unspeakably vile video on the Web gets elementary school kids to drop the "f-bomb" on people who oppose gay marriage.

On the other hand, think how horribly the gospel is disfigured and legitimate protests are marred when members of a now infamous church carry signs at funerals that read, "God hates fags" and, "Thank God for dead soldiers." How do people think they advance their cause with posters depicting the President as the Joker from the Batman movies?

Our country is grappling with many high-stakes, emotionally charged issues: government spending, war, medical care, collective bargaining rights, abortion, gay marriage. Our democracy cannot prosper if people vilify, slander, and even shout down those with whom they disagree.

We should defend our positions vigorously and with conviction—but with civility. Scripture tells us to always be ready to make a defense for the hope we have in Christ—which leads to the convictions we carry—and yet to "do it with gentleness and respect, having a good conscience, so that, when you are slandered, those who revile your good behavior in Christ may be put to shame" (1 Pet. 3:15-16, ESV).

That is why our nation more than ever needs the spirit contained in King's "Letter from Birmingham Jail." And why more than ever, we should re-read it.

We Christians should take another cue from King: "Love even for our enemies," he said in a sermon, "is the key to the solution of the problems of our world."

To speak the truth in love may entail, as it did for King, long-suffering as well as courage on our part. But love does not retaliate. Real love follows the example of Jesus, who "when he was reviled, he did not revile in return; when he suffered, he did not threaten," but entrusted himself to his heavenly Father (1 Pet. 2:23, ESV).

Copyright © 2011 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Previous coverage of Martin Luther King Jr. and racial reconciliation includes:

In Praise of Confidence | Doubt is to be endured, not celebrated. (March 21, 2011)

Behold, the Global Church | It's time we figured out how to talk—and listen—to one another. (November 17, 2006)

CT Classic: Confessions of a Racist | It wasn't until after Martin Luther King Jr.'s death that I was struck by the truth of what he lived and preached. (January 1, 2000)

Articles on confrontation and rebuke in Christianity Today's sister publications include:

The Gift of Rebuke | An examination of what makes rebuke effective and why God gave it to us. (Leadership Journal, October 1, 2002)

Pastor, I'm Offended | A pastor's reflections on confrontation within the church body. (Leadership Journal, April 1, 2000)

Four Laws for Confrontation | Looking to the Bible for advice on church discipline. (Leadership Journal, July 1, 1984)

Previous columns by Charles Colson include:

An Improbable Alliance | Catholics and evangelicals used to fight over religious liberty. Not anymore. (April 11, 2011)

Doctrinal Boot Camp | Conforming to the truth of the faith is necessary for survival. (February 21, 2011)

The Lost Art of Commitment | Why we're afraid of it, and why we shouldn't be. (August 4, 2010)