In the late 1970s, the holy rockers of the nascent Jesus music movement distinguished themselves from their mainstream counterparts even further with one radical step: They discovered social justice. And they did something about it. Little did they know how much their actions—and those of the musicians who followed suit—would impact the world.

Christian music pioneers like Randy Stonehill and Phil Keaggy began partnering with Compassion International in 1979, promoting the evangelical organization’s child sponsorship program from the stage and in their album liner notes. Since then, many Christian artists—including Amy Grant, Michael W. Smith, CeCe Winans, MercyMe, Casting Crowns, and Third Day—have partnered with Compassion and World Vision, some earning stipends from the nonprofits. The results are impressive: Due to artist partnerships, more than 1 million children have been sponsored through Compassion International and World Vision. And in 2008, musicians brought in 49 percent of new World Vision sponsorships.

Yet such compassion campaigns are not new among evangelicals. In 1883, gospel singer Ira Sankey joined evangelist Dwight L. Moody in Edinburgh to raise £10,000 (equivalent to $373,000 today) to build a permanent home for Carrubbers Close Mission—which still offers the homeless a free breakfast on Sundays. And George Beverly Shea, known for providing the soundtrack to Billy Graham’s crusades, often sang to move crowds to support the relief work of Samaritan’s Purse. Cause-driven music and celebrity endorsement carry great credibility.

But something more than endorsement is happening in contemporary Christian music. Artists are directly immersing themselves and their audiences in missions to hurting people, whether they are six blocks or 6,000 miles away. They are stepping to the forefront to address poverty, human trafficking, HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other fatal diseases, taking personal responsibility to invest in grassroots work.

The activism surge among Christian artists is a welcome sign of spiritual maturity, says former Gospel Music Association president John Styll. “The gospel obligates us to joyfully go out and serve those less fortunate.”

The Bono Factor

Musician-led activism crossed a threshold in December 2002 when Bono traveled to Nashville, a stop on his AIDS-awareness Heart of America tour, to meet with Christian bands and artists. At the “Nashville Summit,” the U2 frontman made a strong case for their involvement in ministry to people dying of HIV/AIDS, especially in Africa. He faced anything but a skeptical crowd. Tai Anderson, bassist for Third Day, drank it all in; as he told one reporter, “Dude, you had me at hello.”

Even before the Nashville Summit, many of the artists were already on spiritual pilgrimages. Young artists were starting public activism early in their careers. Some were moving beyond endorsements, going to slums on short-term missions and visiting their sponsored children. A few dreamed of creating stand-alone charities to support their visions.

Their exposure to chronic poverty in the developing world was also beginning to shape their lyrics. Following Bono’s lead, Steven Curtis Chapman, Sara Groves, Jars of Clay, Derek Webb, and others wrote and recorded songs about fatal shootings at public schools, post-genocide poverty in Rwanda, famine, and urban decay. Many of their songs had strong scriptural resonances. Webb’s “Rich Young Ruler,” based on the synoptic Gospel narrative, drew a stark contrast between a prosperous American lifestyle and Christ’s call to draw close to the poor:

We moved out of Jesus’ neighborhood where he’s hungry And not feeling so good from going through our trash; He says, more than just your cash and coin, I want your time, I want your voice.

The prominence of Scripture in their songs set them apart from secular artists’ advocacy, which first gained wide attention through the efforts of Irish rocker Bob Geldof and his Band Aid productions and Live Aid concerts. About a month before Christmas in 1984, Geldof, moved by a BBC report on famine in Ethiopia, gathered top artists for the Band Aid project to record “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” to raise funds and awareness. The proceeds from subsequent record sales, Live Aid concert donations, and merchandise—more than $200 million—were turned over to the Band Aid Trust. Last year, the British charity spent $10 million on relief and development projects in East Africa. It remains a nonsectarian organization.

Musician-led activism crossed a threshold in December 2002 when Bono traveled to Nashville to meet with Christian bands and artists.

Holism without the Hole

In interviews with several Christian artists, Christianity Today found that Christian musicians—including those featured on the following pages—had done their homework before undertaking cross-cultural missions work.

Scott Moreau, professor of missions at Wheaton College, believes there is good reason for Christians to be enthusiastic about these artists’ thoughtful activism. “Most [artists] are partnering with groups that have their act together, like World Vision, Food for the Hungry, and International Justice Mission,” he says. “They are using their platforms in ways that are kingdom appropriate. They’re infected with this vision, and that’s something any missiologist can cheer.”

Moreau says they are wise to avoid the minefield of short-term missions, which can create ineffective dependency and undermine local initiatives. But he cautions artists not to get so caught up in social justice that their work becomes “holism with a hole.” In other words, he says: Don’t forget to share the Good News.

“It’s rare for evangelicals to drop the social engagement ball,” says Moreau, “but not as rare for them to drop the evangelism ball. I’m not an old curmudgeon who says, ‘Evangelism and nothing else.’ [But] this is something these artists and their ministries need to keep in mind.”

Achieving sustainability is another great challenge in humanitarian work. Steven Garber, director of the Washington Institute for Faith, Vocation, and Culture, has worked with a spectrum of recording artists, including Bono and Jars of Clay. Garber believes faith in God is a stronger and more sustaining motive than just about anything else. “Václav Havel said that when you lose God, you lose access to meaning, purpose, accountability, and responsibility.

“Believing in God has consequence, so a Christian has access to sustainable reasons to keep at something,” he says. “It’s difficult to keep something from becoming a cause du jour, but if it’s really a calling from God, you’re going to be able to draw on resources that enable you to keep at it when it gets really hard.”

Mark Allan Powell, author of the Encyclopedia of Contemporary Christian Music, says the connection between musician and audience activism has gone through many evolutions.

“Bono’s activism has certainly inspired audiences. College and high school students in general seem to be more committed to social action and responsibility than at any time since the 1960s.”

Jars of Clay lead vocalist Dan Haseltine was at the Nashville meeting with Bono. “Bono definitely put some of the ‘sexy’ into community development,” he told CT. “You want people to think it makes them cooler to be involved, because it does. It keeps them connected to suffering. If we’re not connected to suffering, we lose a great deal of depth.”

Steven Curtis Chapman credits his daughter Emily—who encouraged her parents to adopt orphans from China—for helping him to think through social justice and Christian engagement in a sinful world.

“Emily looks at James 1:27, about taking care of widows and orphans and keeping oneself unspotted by the world. She is saying, ‘If we can just get those two together, we’ll be on a roll.'”

Direct to Disciple

The burgeoning activism within Christian music is happening against the backdrop of a tumultuous music industry. Music sales in the United States have declined in seven of the past eight years, and digital sales have yet to fill the gap left by shrinking CD sales. Illegal file-sharing has also cut into profits.

Some musicians are reacting by taking their music directly to listeners, using the Web to build tight communities around their work and interact more closely with fans. Chicago Tribune music critic Greg Kot recently observed that “the industry, like the music itself, is fragmenting into community-based niches and subcultures.”

These developments may spell financial misfortune for the industry at large, but they can play to the strength of Christian recording artists invested in missions. The relationship between artist and listener is closer than ever. There is greater potential for audiences to buy into the passion of the musician. Musical expression, mission, and message converge in a way that touches listeners and moves them to action. They begin seeing the artist as a credible model for activism—and realize they don’t have to be a rock star to help drill a well in Africa, adopt a child from China, or simply love their next-door neighbor.

The following pages feature a number of musicians who embody the encouraging changes in the world of Christian music—changes anyone, whether a music fan or not, can celebrate.

Copyright © 2009 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Christianity Today also posted the following articles as part of the cover package:

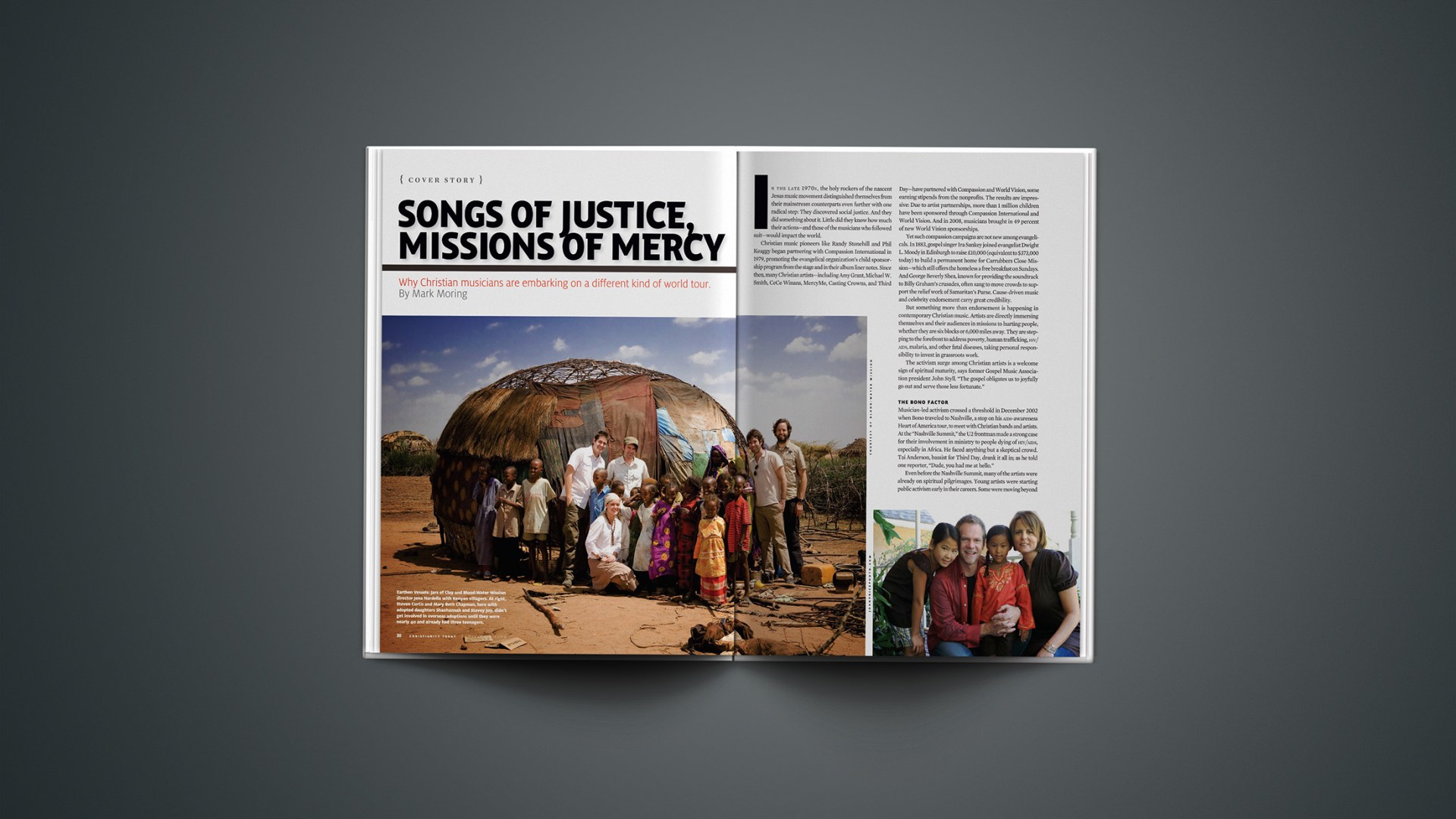

Jars of Clay: Clean Water, Clean Blood

Sara Groves: Less Charity, More Justice

Steven Curtis Chapman: Beauty Will Rise

Derek Webb: A Different Kind of Neighbor

Third Day: Diversification Is the Key

Previous Christianity Today articles on social justice and musicians include:

More Than a Sexy Cause | Social justice is ‘fashionable’ these days, but how do we keep it from being just a passing fancy? Donald Miller and others addressed that question in Nashville recently. (July 28, 2009)

Jesus at G8 | Christian advocacy for Africa gains notice at top meetings. (July 6, 2005).

Bono’s American Prayer | “The world’s biggest rock star tours the heartland, talking more openly about his faith as he recruits Christians in the fight against AIDS in Africa.” (March 1, 2003)