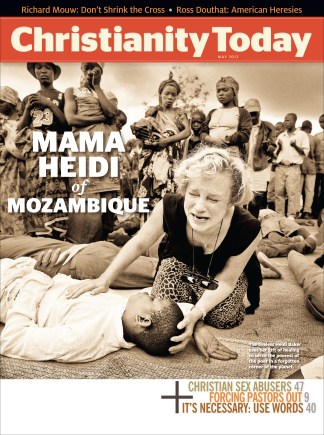

"I want anybody who is deaf to come to the front. Anybody who can't hear. God is going to heal tonight." Heidi Baker, with short, swept-back blond hair, hawk-like blue eyes, and Teutonic features, speaks over a powerful sound system into a pitch-black African night.

We are in the dusty village of Chiure, Mozambique, the 11th poorest nation on earth. No electricity or running water is available here. From their ragged clothes and bare feet, you can see that the people are destitute. Two trucks have brought students from Pemba, Baker's mission center. Setting up open-air screens and generator-powered projectors, they have just shown the Jesus film. Preaching followed. And now, a crowd of several hundred has gathered on the bare ground in front of the trucks for the climactic moment.

Heidi Baker, known worldwide for her healing miracles, spends a third of every year on the charismatic speaking circuit, where people routinely fall to the floor in unconscious bliss or shake and laugh uncontrollably. They come, enthralled, to hear of Baker's miracles in places like Chiure.

In recent years, she says, 100 percent of the deaf in the Chiure area have been healed through prayer. Not only that, she claims, scores have risen from the dead, food has been multiplied, the crippled and blind have been restored, and the gospel has spread like fire. Baker's church association now numbers 10,000 congregations, maybe more.

Responding to Baker's call, four people straggle to the front, standing uneasily. The audience crowds forward around them, blocking the view. Most of what happens is relayed over the booming sound system in Portuguese and translated into Makhuwa, the local language, with occasional explanations in English. One can hardly see through a blinding floodlight on the truck.

Attention focuses on Antonio, a somber boy of perhaps 12 who, as a young child, it is said, lost his hearing completely.

Antonio cannot explain himself, because he cannot hear or apparently speak. Baker asks the audience for help. "Do you know Antonio? Is he really deaf?" Only a few people seem to respond. But Baker is satisfied and proceeds to lay hands on Antonio and pray.

Then she gives Antonio a microphone. "Ba-ba!" she shouts, her voice booming through the sound system loudly enough to make the deaf hear. "Ba-ba," Antonio repeats in a strangled, calf-like mew. "Ma-ma!" Baker shouts. "Ma-ma," Antonio repeats.

"Jesus," Baker cues.

"Jesus."

Baker announces jubilantly that Antonio is completely healed, and that, in fact, all four people on stage have been healed of deafness. She invites the crowd to praise God, but the response is weak. Later, when asked about the subdued reaction, she says, "It's always that way in Mozambique. They never show much reaction."

Her assistant Antoinette, who has seen many Mozambican healings, agrees. "It seems odd," she says. "We would be jumping around."

Was it a miracle? Unless you knew Antonio before and after, you couldn't say for sure. Baker, though, has no doubt, and nobody else seems to either.

After the healing, Baker asks for villagers with bad backs to raise their hands so that members of the outreach team can find them and pray for them. Then come those with stomach problems. Finally, she invites drunkards who want healing prayer to identify themselves, and a few do. The evening program concludes with outreach team members circulating through the crowd laying hands on and praying for anyone who wants it. Plenty of people seem eager. Some indicate that prayers have been answered.

It was during this time of prayer, Baker later says, that the village chief approached her. "Did you see Antonio healed?" she asked him. He said he had seen it. He then announced that the elders would like to donate land where Baker could build a church, which could double as a preschool and meeting center. He also invited Heidi and husband Rolland Baker's umbrella organization, Iris Ministries, to come drill a well. In Chiure as in so many places in Mozambique, healing has opened the door for God's love.

Loving the Abandoned

Rolland Baker, Heidi's husband and mission partner, says Heidi is fundamentally an introvert, longing for hours alone in prayer and meditation.

Most days, however, she spends interacting one on one with dirty and ragged children like those who circle around her from the moment she arrives in Chiure. One of the mottos she preaches is, "Stop for the one." She lives by it. As a result, she is prone to arriving late.

After a night sleeping on the ground in Chiure, Baker visits in homes. The houses are simple adobe structures of one or two rooms, their roofs made of a loose thatch, their floors dirt.

Heidi has a gift for making friends—sitting with women by their front door, praying for them or their children, laughing and talking.

Baker has a gift for making friends—sitting with women by their front door, praying for them or their children, laughing and interacting. She seems completely at home here. She prays for a boy with epilepsy. Though perhaps 8 years old, he has not been in school. From the quarter-size scar on the top of his head, it seems that he has been trepanned, a primitive surgical treatment that removes bone from the skull. "Don't go back to the witch doctors," Baker sings out as she moves on.

At another home, Baker sits with a smiling mother and her newborn, taking a language lesson in the local dialect. The mother says she must walk nine miles to find potable water. "This is why we drill wells," Baker says. "Love looks like something."

Love looks like many things for Heidi and Rolland. They start schools, offer medical clinics, distribute food, and drill wells. They also pray for miracles. "If God doesn't show up, we fail," she likes to say.

Michael McClymond, a theology professor at St. Louis University who has visited the Bakers in Mozambique, summarizes their ministry model: "Go out on a limb and wait for God to show up."

Isn't that putting God to the test?

McClymond thinks not, "because it's done on behalf of the poor."

Another Western scholar sees the Bakers as among the most influential leaders in world Pentecostalism. Indiana University religious studies professor Candy Gunther Brown has studied the Bakers in the field. She says, "Heidi is a hero to young women," so much so that scholars joke about "Heidiolatry."

"For Heidi and Rolland, miracles and concern for the poor are meant to go together," Brown says. "In their view, you can't separate the two. Power and love are wings, and you need both to fly."

Rolland and Heidi make a team, with Heidi as the outgoing public celebrity and Rolland as the behind-the-scenes engineer. Rolland grew up in Taiwan, the son of Assemblies of God missionaries. Heidi is 12 years younger, a Laguna Beach teenage convert to Pentecostalism. They met while Heidi was an undergrad at Vanguard University in California. Shortly after their wedding, the couple left for Indonesia with a one-way ticket and little money.

They spent over a decade in Asia, specializing in music-and-drama evangelism. Their two children were born there. And they increasingly became attracted to the poor. They found their calling after reading a Time magazine article about Mozambique, which described its embroilment in a desperate civil war (1977-92).

A stint at King's College London enabled the Bakers to pursue doctoral studies in theology while ministering to the down and out on London's streets.

In January 1995, Rolland was invited to speak at a pastor's conference in Maputo, the capital of Mozambique. Visiting a government orphanage, he discovered a rundown facility crammed with malnourished children.

Rolland imagined a spiritual revival among Maputo's despised and abandoned children. Returning to London, he began negotiating with Mozambican officials to get permission to take over the orphanage.

Heidi traveled to Maputo that summer after finishing her dissertation, a "reconstructive theology" of speaking in tongues (glossolalia). She had little money and no real plan. She did what she does best: She visited the orphanage and talked to the children.

They kept their distance when a white woman first drove up to their isolated compound. It was widely believed that white people came to steal children.

"I was playing in front of the office," says Sergio Mondlhane, now in church leadership in Pemba. "She approached us, kneeled down, and asked our names. I remember that she smelled good. She gave us candy, and she said she would come to see us again." But the children were skeptical, because they had heard that before.

Heidi did return, however. Jacinto Maria Rageje said, "She was the one who led us to Jesus. The biggest thing was, she cared for every single one. We couldn't believe it. We didn't need people to bring stuff. We needed someone to pay attention to us."

Baker brought food when she could. She organized repairs for facilities. She befriended the staff and eventually moved into a renovated house on the base. (Rolland and their two children remained in Maputo, and they all traveled back and forth.)

From the streets of Maputo, they brought more and more deserted children to the orphanage, until the numbers more than tripled. Children's thin bodies began to fill out, and many gave their lives to Christ.

Everything Falls Apart

Then came perhaps the greatest and most important crisis of Baker's life. She caught pneumonia and couldn't shake it. "I was exhausted and getting steadily weaker and sicker. The constant responsibility of having over 300 children looking to me as their 'Mama Aida' had simply worn me out."

While his wife was sick, Rolland visited the Toronto Airport Vineyard Christian Fellowship (now known as Catch the Fire), where the controversial Toronto Blessing revival of the mid-1990s had broken out. It was marked by ecstatic manifestations of the Holy Spirit, most notably "holy laughter."

Hearing his report, Heidi became convinced that she desperately needed to visit Toronto. Against medical advice, she signed herself out of the hospital and took the long flight to North America. While visiting her parents in Laguna Beach, she was rehospitalized. Again, she checked herself out. At the first meeting in Toronto, her lungs opened up. She spent much of the following days draped on the floor, praying and being prayed for. Never before, she says, had she experienced the love of Jesus in such a tangible way.

One night, she had a vision of Jesus in which she literally ate his flesh and drank his blood. He spoke to her about the children who so burdened her. "There will always be enough," he said. Heidi took it that they were not to pull back or limit their program. They were to care for every child they encountered and to count on Jesus to provide. As he had cared for her, he would for them.

Renewed, she returned to Mozambique.

And almost immediately, everything fell apart. The Bakers' carefully cultivated relationship with the government became adversarial, to the point where all religion was banned from the orphanage. The children were not to pray and sing even under a tree. Outraged, the children defied the order. Iris Ministries was then ordered to leave the orphanage within 24 hours. The staff worked all night packing up their goods.

Some of the children rebelled and ran away from the orphanage, following Baker to her home in Maputo. She had nowhere to send them. Rageje recalls Baker's desperation. "She told us, 'I may go back to America. I have no money.' She was ready to quit, but she didn't quit. And she was the last hope we had." Baker urged the children to pray for God to open doors. Remembering her vision, she offered what little food and space she had, letting them sleep in her garage.

Eventually, a Mozambican elder gave Iris some property outside of town. There was nothing there—no electricity, no water, no buildings. But they housed the orphans in army tents and in South Africa bought a huge revival-style tent to use for schooling and worship.

In less than a year, Iris was able to purchase property in Maputo, where they built dormitories, developed a ministry center, and began a small Bible school.

Ninety Mozambican churches eventually decided to affiliate with Iris. Pastors came from rural villages to the school for three months of training. At one session, Heidi prophesied to two of the pastors that they would raise people from the dead. Soon there were reports of the wife of a district official rising from her deathbed after two hours of prayer. News spread fast of astonishing miracles, and church numbers multiplied.

A surge of growth came in the aftermath of enormous natural disasters. In February 2000, and again in 2001, terrible flooding displaced hundreds of thousands of Mozambicans. Iris's rural center was also flooded, and relief efforts overwhelmed the country's capacity.

Still, the Bakers led their team in delivering aid to camps with thousands of refugees, transporting and distributing tons of food. They soon discovered that people were as hungry for spiritual nurture as they were for food and water.

Up to this point, the Bakers had mainly focused on urban children. But engaging in flood relief, the Bakers soon developed a national ministry reaching all ages. Churches burgeoned too quickly to count. Not long after, they opened a base in Pemba, in the largely unevangelized north.

Iris Distinctives

Pemba, one of Iris Ministries' 14 bases in Africa, is a shadeless compound of sand and rock, strewn with mammoth baobab trees. Its buildings are simple block structures with tin and thatched roofs. But this unassuming place is the nerve center for the visions that Rolland and Heidi believe God has granted to them.

From anywhere on the campus, you can see the deep blue of the Indian Ocean. A handful of tourists come to Pemba to dive its coral reefs or lie on the sand. But the base in Pemba is no tourist resort.

Rolland Baker, Heidi's husband and mission partner, says Heidi is fundamentally an introvert, longing for hours alone in prayer and meditation.

Pemba has messianic excitement, a sense of constant expectation and maximum commitment. For six months of the year, almost 300 English-speaking students live here. These Harvest school students are almost all white, ages 18 to 25, and from North America, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Holland, and Sweden. Women greatly outnumber men. Everyone lives six to a room in stifling conditions without air conditioning. They eat Mozambican beans and rice nearly every day, they sometimes do without water for washing, and once a week they travel to villages to sleep in tents and do outreach.

They share the campus with 300 Mozambican Bible-school students. These mostly young men deeply desire to become pastors. Most are barely literate. Despite the vast cultural gulf, Westerners and Mozambicans worship together, eat together, and go on mission together.

The base also houses 200 orphans. Vocational training and food distribution bring dozens of poor, deserted women, along with a number of disabled men, to the campus each day.

Some 2,500 students study at the primary school. At any given time, there are likely to be 50 other Westerners: full-time Iris missionaries, guest speakers, mission teams, and visitors. It's a big and busy place, with an expanded medical clinic under construction and a half-finished "baby house" for abandoned infants.

New ideas surface unexpectedly, but there are definite themes. One night Rolland sits in a darkened room and enumerates Iris Ministries' distinctives:

• First, the Bakers believe in the possibility of experiencing God. Heidi speaks of ministry flowing from "your secret place" in a love experience with Jesus so potent it verges on the erotic. (Scholar McClymond describes Heidi as a "practical mystic, like Teresa of Avila.")

Much of this emphasis comes from the Toronto Blessing, where Heidi had her breakthrough experience. Though they have lost financial support due to their association with the Toronto movement, the Bakers are loyal to its leaders and attend their Catch the Fire conferences in North America every year. Several leaders involved are active in the so-called New Apostolic Reformation, a controversial charismatic movement. But the Bakers do not promote the New Apostolic Reformation or consider themselves to be modern-day apostles.

• Second, the Bakers expect miracles as a normal part of the Christian life. They provide medicine and food as they are able, but miracles are central. "It's not just Heidi," Jose Lino, a visiting pastor, says. "I see the same miracles when I pray for healing. It comes from God alone."

Another pastor who brings teams of young people to Pemba observes, "Here, healings come easily. We've prayed for the blind all over the world, and only five times have people been healed. But here, it happens most of the time. To tell you the truth, I don't understand it."

Indiana University's Brown was so intrigued by claims of healing that she sought to verify them scientifically. With a small team she traveled to Mozambique to accompany Baker on outreaches. Testing 24 Mozambicans before and after healing prayer—half performed by Baker—her team detected statistically significant improvements in hearing and vision. (The results were published in the September 2010 edition of the Southern Medical Journal, and are available online.) Brown's team found similar results on an excursion to Brazil, but testing at charismatic gatherings in North America did not yield significant results.

One night she had a powerful vision of Jesus in which she literally ate his flesh and drank his blood. He spoke to her about the children who so burdened her. 'There will always be enough,' he said.

• Third, Heidi and Rolland emphasize going to the poor and the powerless. Caring for human needs is not a sideshow—it is the main show. "Seek out the most marginalized you can find," Rolland says.

• Fourth, they expect to suffer, and so reject a theology that claims Christians deserve an easy life. The Bakers' home near the Pemba base is simple and functional, a place to welcome their numerous adopted children and to host sleepovers for the current crop of institutionalized children.

Though Heidi's stories almost always end in miraculous victory, she points out to Pemba students that Iris children die, that they build homes for blind people who aren't healed, and that suffering continues in spite of prayer. The Bakers have both suffered severe sicknesses. Close to memory is Rolland's breakdown several years ago, when he suffered inexplicable dementia and lost virtually all functionality for many months.

• Fifth, the Bakers emphasize the joy of the Lord. At Sunday morning worship in Pemba, a very lively dance troupe leads the congregation in complicated steps. Prayer times are exuberant. The laying on of hands may be accompanied by raucous laughter and whoops of joy.

Living Face Down

On Tuesday and Thursday mornings, Heidi teaches local student pastors and visiting Westerners at the Harvest School in Pemba.

They gather in a large, hillside shed, a concrete slab with a roof for shade. To face the heat, students wear shorts or loose-fitting skirts, T-shirts, and flip-flops. They sit on the floor or stretch out as a guitarist leads in the ultimate worship song of three chords, four words, repeated 50 times. "Welcome in this place," words addressed to Jesus, are repeated without variation at least 200 times, lasting for 30 minutes.

Some students kneel with eyes closed and hands lifted high, swaying themselves into a trance. Others lie on their backs with hands lifted straight into the air. Still others seem unengaged by the music, looking around or even quietly conversing with neighbors.

Baker slips in behind the guitarist, placing herself prone on the floor, her arms outstretched. Several women gather to lie beside her, massaging her and praying. She does not move as the song endlessly repeats. Then, slowly, she raises herself to her knees and leads a continuation of the music, improvising words in a strong, deep voice.

She is attractively dressed in bright colors, with a turquoise necklace and earrings. She launches into the Beatitudes. That's what preoccupies her with these students—those "scary" words of Jesus that ask so much. "Blessed are the poor in spirit," she tells them, which translates to "live face down" before the King of glory.

She mentions her deep concern for children held captive in the worldwide sex trade. Baker is not strikingly articulate, but she dramatizes the existential state of her soul—emotions of inadequacy mixed with complete dependency on a loving Jesus. "I'm desperate and yet fulfilled at the same time, because I know my Daddy is there for me." In ministry, she says, "The way up is down."

She is a storyteller, and today she illustrates with a story of church crisis. One Mozambican pastor was caught in adultery and theft. Suddenly leaderless, the church needed help. Baker says God told her to walk to a certain tree, where she would find it. What she found was a young man who had just left jail. He needed a job and his mother, a Christian, had told him to sit under the tree and wait. He didn't seem like a promising prospect, but Baker says she took God at his word and invited the man to join their work. Today he is a co-leader of the whole Partners in Harvest missions organization under the sponsorship of Iris.

She tells of a wedding in Maputo where cholera in the salad infected hundreds of people. Some went to their homes and died, but 80 who lived at the base went into a special cholera hospital. The medical staff said they would all die, too, but Baker and another pastor went to offer what love and care they could, "face to face, cheek to cheek," heedless of the filth and the possibility of getting infected. Miraculously, all 80 recovered. The doctor who had predicted death told Baker, "Your God is God," and asked to join their staff.

A third story: a Mozambican pastor screaming, wailing, and shaking in church. When Baker asked him what was troubling him, he answered, "God told me to give away everything I own!"

"We don't pay our pastors," Baker explained. "If we did, it would destroy the church overnight." Jose owned nothing, not even a house. What would his wife think? He had been accumulating building materials, but he donated them to build a church. Subsequently, a visiting Australian announced to Baker that "God spoke to me," and that he was supposed to build Jose a house. When Jose got the house, he took in orphan kids to fill it.

"Riches are a very sad thing unless they are used to raise up the poor," Baker says. "True riches look like people coming to the Father, into his house. Riches look like children.

"Jose is the richest man I know."

She smiles and asks the students, "Do the Beatitudes scare you like they did before?" Pausing to let the question sink in, she looks around at the rapt faces. "I hope your answer is, 'Yes and no.'"

She carries on to the next Beatitude, "Blessed are those who hunger and thirst after righteousness." Baker regrets that they no longer have space to combine the Harvest School with the Bible school. When the classes were joined together, she would ask, "How many of you have had a family member die of starvation?" Thirty or forty Mozambican hands would go up.

"They raised their hands without emotion. It was just matter of fact. One man lost nine children to famine. He took in nine orphans. I've never seen love like that.

"I would have the Mozambicans lay hands on the Westerners and Easterners and ask God to teach them what hunger is like.

"I am hungry for righteousness to be poured out on this earth," Baker says, as Jesus was.

Strikingly, her stories feature Mozambicans more than herself. Pastors are raised into leadership by God's choice. They manifest the deepest faith and greatest riches she has seen. In their poverty, they understand the words of Jesus. She wants the idealistic Western kids at the Harvest School to grasp the practical import of the Beatitudes, which is humility. She wants them to sacrifice their lives to the call of gospel ministry, to throw their lives on Jesus.

She tells about Iris Ministries' new boat, purchased to reach offshore islands where people have never heard the name of Jesus. "If it means you need a ship to get there, hunger and thirst for it. You don't say, 'We're already overextended.' You don't give up. You get there."

Heidi and Rolland Baker seek to prove the gospel in the hardest places, to see the impossible flow out of the love of Jesus. They want to transform Mozambique, and beyond, but they operate hand-to-mouth, always running on the ragged end of their resources and organization. Their leadership drives Iris, but they cannot go on forever. Rolland is in his mid-60s, Heidi in her 50s. Sustainability ultimately depends on thousands of African pastors, alive with faith but virtually untrained, and hundreds of idealistic young Westerners who have experienced Pemba and are committed to serve anywhere. If the ministry is to be sustained, it will have to be by the power of the Holy Spirit, say the Bakers.

Heidi ends the session with an emphatic, shouted prayer. "I pray that I stay wrecked the rest of my life!" Bodies are scattered over the floor. There is a deep drumming of tongues. Hands are raised. Hands are laid on heads in passionate petition. Some shout angry defiance at Satan. Some cry out as though in pain.

Tim Stafford is a senior writer for Christianity Today. His book on miracles will be published this year.

Copyright © 2012 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Christianity Today has an accompanying photo slideshow of design director Gary Gnidovic's visit to Mozambique.

Previous CT miracles about miracles include:

It's Okay to Expect a Miracle | Scholar Craig Keener rediscovers the reality of divine intervention. (December 9, 2011)

God's Quiet Signature | Why the rescue of the Chilean miners was a "great miracle," and what it tells us about Hanukkah. (December 13, 2010)

Miracle Boat | The surreal, sometimes comical story behind the discovery of the Jesus Boat. (April 22, 2010)

Needed: More 'Miracles' | My grandchild barely survived birth. Worldwide, too many newborns do not. (December 3, 2008)

Miracles | Quotations to stir the heart and mind. (February 4, 2008)