Last week, a video was leaked of a white man shooting and killing Georgia jogger Ahmaud Arbery in his neighborhood in Brunswick, Georgia. While Arbery’s death occurred in February, the alleged shooter and his father were only arrested last week following a massive public uproar following the release of the tape.

Many Christians, of all racial and ethnic backgrounds, have condemned the Arbery’s killing. But widespread condemnation from the church for these types of killings was not always the case.

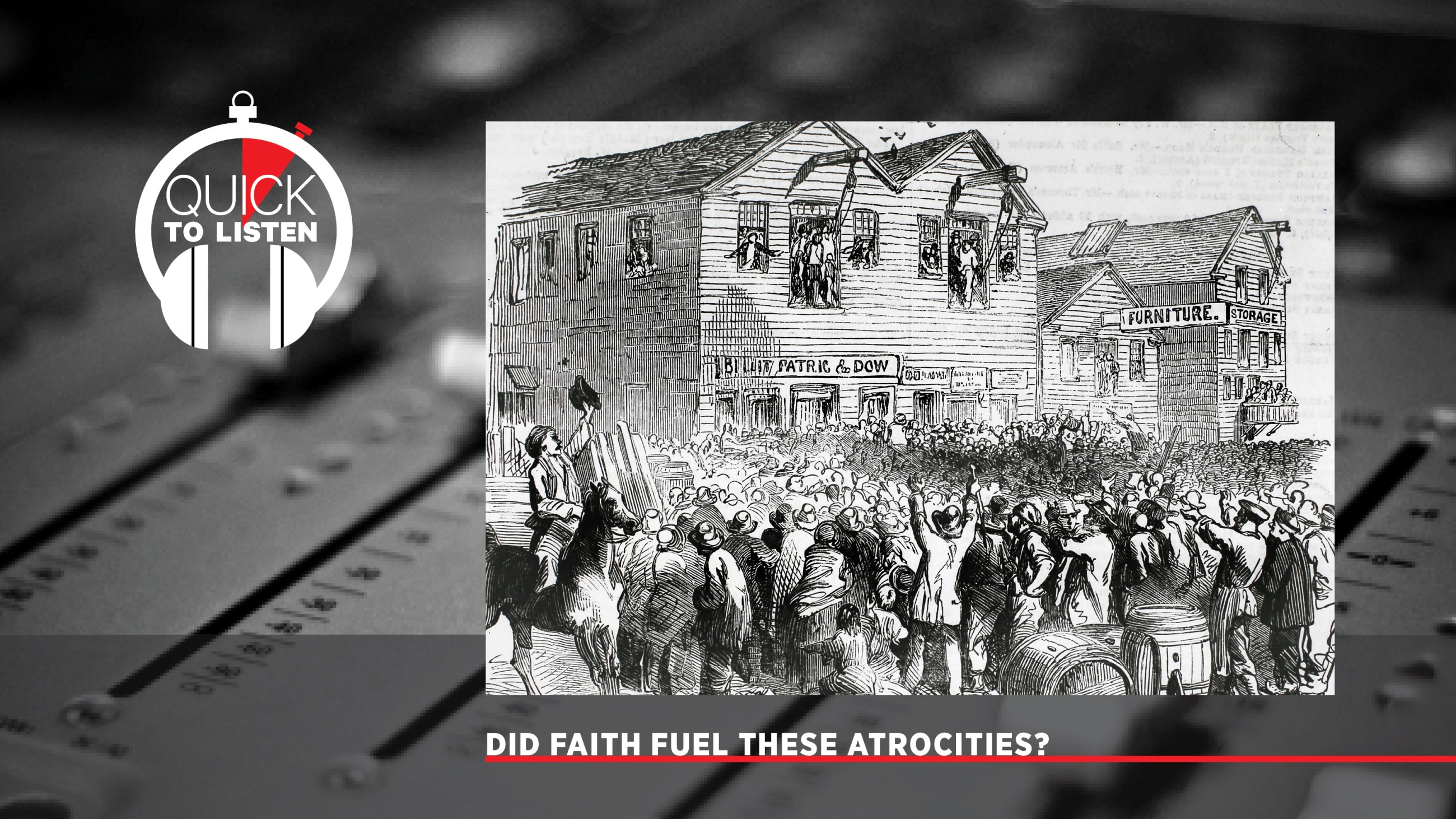

For years, for white Christians, “the critique of lynching rarely moved beyond ‘Lynching is anarchy, and we need to kind of reinforce the rule of law,’” said Malcolm Foley, a PhD candidate in Baylor University’s Department of Religion, whose dissertation examines African-American Christian responses to lynching from the late 19th century to the early 20th century,

Not surprisingly, the black church took a much more forceful response to these atrocities.

“Many black pastors were commenting on this and saying, ‘If you can either stand in a mob of thousands of people and watch a black man be set on fire alive, or if you are one of the people holding the rifles that riddled this body with bullets, you're most likely not a Christian,’” said Foley, who is also the director of discipleship at Mosaic Waco.

Foley joined digital media producer Morgan Lee and editorial director Ted Olsen to discuss the colonial history of lynching, how beliefs about white women provided justification for this violence, and how lynchings changed the theology of the black and white church.

What is Quick to Listen? Read more

Rate Quick to Listen on Apple Podcasts

Follow the podcast on Twitter

Follow our hosts on Twitter: Morgan Lee and Ted Olsen

Follow our guest on Twitter: Malcolm Foley

Music by Sweeps

Quick to Listen is produced by Morgan Lee and Matt Linder

The transcript is edited by Bunmi Ishola

Highlights from Quick to Listen: Episode #212

The best way to start this conversation would be by talking about historical background and defining terms. So when we're talking about lynching, how do you define that and where does that term come from?

Malcolm Foley: [Lynching] is a fraught term, and historians and anti-lynching activists have kind of fought for this definition for a while.

The definition that I'll give is one that Manfred Berg gives in his book Popular Justice, where he says that lynching is essentially an extra-legal punishment that's meted out by a group of people claiming to represent the will of a larger community and with an expectation of impunity.

There are debates over what constitutes a group. There are debates over what denotes the will of the larger community. But that's a good place to start.

The term itself, for American history, originates around the period of the American Revolution. There are a few circulating stories about the origin of the term, but probably the most convincing one is of the Bedford County, Virginia militia, which was essentially lynching Tories during the American Revolution. The leader of this militia was Charles Lynch, and he referred to the way he tracked down lawbreakers outside of the law as lynching.

Lynching didn't always include death. It was often things like flogging, tarring and feathering, and exiling. But in the late 19th and early 20th century, it becomes an almost exclusively racial practice. But the category of extralegal punishment is what we're thinking of when we think of lynching broadly.

Can you help us better understand what led to the distinction between racialized lynching and the “frontier justice” type of lynching?

Malcolm Foley: In the late 19th and early 20th century, in a number of American populations you had very weak law enforcement agencies. So for some, lynching was the avenue that communities took for this “frontier justice” idea. So up until about the late 1880s, you have white and black people being lynched by mobs.

During the period of Reconstruction, you start to see those numbers go up as white southerners who are sympathetic with free people and white northerners who are coming down to educate the recently freed are killed by groups like the Ku Klux Klan and other paramilitary groups.

In the late 1880s, during a period of what can be called Redemption, the number of white people being lynched drops and the number of black people being lynched skyrockets, to the point that you have upwards of 70% of the people being lynched are black.

It's at that time that narratives start circulating about black men being sexualized beasts and things like that. And so, for white communities to protect themselves, specifically to protect their women, the black beast rapist needs to be removed violently and publicly.

In many of these communities, they have law enforcement, it's just that mobs think that law enforcement doesn't act quickly enough. So the frontier justice thesis doesn't stand up as much, specifically when you start looking at the racialization of lynching post-1886, because they have robust justice systems—that would still be extremely biased against the black man or woman—but there was the belief that it won’t act with the kind of decisiveness that the mob would.

How does the religious aspect come into play with this mindset? As lynching became racialized to what degree did people see God in it?

Malcolm Foley: I would be reticent to over theologize this. I think that for some—and this also how it worked in pro-slavery rhetoric—Christianity functions as a very powerful tool for people to get what they want. And in a society where Christianity had a particular social and political cachet, there were some who sought to mobilize it to that end.

And so when your fundamental commitment is to “protect your women” that took precedent over the recognition of human life. The levels of brutality present in a number of these spectacle lynchings suggests that while you may say that you hold human life to be precious, it's also very clear that you hold some lives to be more precious than others.

When it comes to the way that people would use their faith to justify these particular practices, it’s also helpful to remember that many black pastors were commenting on this and saying, “If you can either stand in a mob of thousands of people and watch a black man be set on fire alive, or if you are one of the people holding the rifles that riddled this body with bullets, you're most likely not a Christian.”

For white Christians, it was rooted in this understanding that one of the things that God does is He blesses particular social orders. When it comes to issues of lynching, if I can find resources that suggest to me that I can be a tool of God's that makes me all the more confident to do so. Even if it means the kind of brutality that took place in the era of spectacle lynching.

Your research focused on how African American Christians were reacting and responding to the lynchings going on during that era. Were they able to prick the conscience of the people they were trying to influence? How much resonance did their arguments have?

Malcolm Foley: I kind of see my research as a prequel to the work of Mary Beth Matthews, who talks about African American evangelicals and fundamentalists between WWI and WWII.

One of the things that she outlines is the fact that you have a period of time where a number of African American evangelicals agree with fundamentalist, particularly on the core of the gospel, but for a number of African American evangelicals, there is a direct link from there to fighting for racial justice. And the fundamentalists are like, “If you're focused on all this race stuff, chances are you're not as orthodox as you say that you are.” And that essentially stops a lot of the conversation.

I'm focusing on about 1890 to 1919, a period of time before the NAACP gets really involved, in anti-lynching work. And one of the things that I continue to find is as much of an opportunity as black pastors have, they're trumpeting the idea that lynching is happening and it is something we need to, we need to deal with, and specifically calling for white pastors to partner with them. And one of the things that you also see as a response is them lamenting over why the white pulpits and white press silent. And that’s an indictment that continues throughout that time.

Eventually, though, it does seem like something breaks through. What changes between the period leading up to the 1920s and 30s that church bodies and congregations are willing to address lynching publicly?

Malcolm Foley: Public sentiment changes.

So it's important to consider this in the way that we consider the modern civil rights movement. I don't see either of those as profound moral revolutions. What happens is—specifically in the case of lynching—when the international communities get wind of it, and you have papers in the UK, in France, in Japan talking about Southern lynching, especially in a period of industrialization ramping up, it becomes very bad for business.

Basically the rest of the nation is no longer going to let you get away with gathering to burn a human being alive. And so you find other ways to fulfill that same goal. You start seeing the rise of Jim Crow legislation and other tactics to still keep black communities in their place.

What does the increasingly globalized economy bring to the table that a few decades earlier, Northern opposition would not have?

Malcolm Foley: Part of it is that Northern is more sporadic in the early years than it is later.

Statistically, the 1890s is the worst decade and it starts to drop over time. But for the experience of African Americans folks, they're not thinking about the aggregate statistics. They're thinking about the fact that this could happen to them at any time, and the terror and of that continues even when statistically it drops off.

But they drop off because more and more people find out about this as journalism develops and these stories are making it all around the country and all around the world. Add to that the Great Migration, where millions of black people are leaving the South, not just for economic opportunity in the North, but also fleeing domestic terrorism. These are part of the matrix of reasons why we see the drop of lynching.

When Ida B. Wells does her international campaign in England, one of her rationales is, “Americans see the British as super civilized. If the British say something about lynching, maybe Americans will.” And that's something that she's doing in the 1890s.

Earlier you said that the African American church and white fundamentalist church often agreed on a lot of theological points, but had a lot of disparity when it came to civil rights. You suggested that the white fundamentalist churches the African American approach towards civil rights as being liberal. Can you unpack that a little bit more? What are some of the specifics they were critiquing them?

Malcolm Foley: It goes back to the fundamentalist modernist controversy. Basically the association is, if you're concerned with all these social movements, you’re essentially an adherent of the social gospel, and those social gospels deny the divinity of Christ. And that’s something that a number of fundamentalists sought to sought to distance themselves from.

On the other side, a number of black Christians are basically saying, “This fundamentalist modernist thing is a debate that's going on in your white churches. We're not debating that. We're on the same page on doctrine. We just also want to live. And the fact of the matter is we're being murdered on it on a daily basis, and we think that you ought to be on the same page as us in thinking that ought not be the case.”

Here are some quotes from Walter White, an anti-lynching activist and NAACP leader:

“It is exceedingly doubtful if lynching could possibly exist under any other religion than Christianity.”

“It is no accident that in these states with the greatest number of lynchings, the great majority of the church members are Protestants and of the evangelical wing of Protestantism as well.”

“It is a well-known fact that revivals and camp meetings often produce an increase in hospital cases of mental disease. No person who is familiar with the Bible-beating, acrobatic, fanatical preachers of hell-fire in the South, and who has seen the orgies of emotion created by them, can doubt for a moment that dangerous passions are released which contribute to emotional instability and play a part in lynching.”

From your perspective, how much of this should we dismiss as anti-evangelical bigotry and how much should we actually see a direct connection between revivalism and racial violence?

Malcolm Foley: That's my favorite Walter White quote to use when I have presentations on this particular topic, because there are others who share that assumption and it can be difficult to extricate the two.

This is one of those things where I see more coincidence than a causative relationship between the two. A number of folks will bring up that these lynching orgies are just an emotionalism writ large, that these are people that have just gone temporarily crazy. But I don't think that covers what's going on there. It's just frenzy. It's more sinister than that. It's rooted in your need to defend something. And in the case of lynching, it's whiteness and white supremacy in general.

And so as much as it may appear to folks that this is just a result of emotional frenzy, I think that cheapens the kind of insidiousness of this, of this particular practice. It takes away the culpability of each and every one who participated in that killing.

Many of the “reasons” for lynchings are often associated with a white woman. Can you unpack what is central to white womanhood in understanding lynching?

Malcolm Foley: That is the central question when it comes to lynching in the late 19th and early 20th century, and it's a result of what I call “The Cult of Southern White Womanhood.” And Ida B. Wells recognized this and fought against this in all her work.

There are these profound racial and gender narratives that undergird lynching. There's a narrative of the black man as a sexualized beast, there's the narrative of the white woman as the non-sexual paragon of virtue, and there's the image of the white man as the kind of violent protector of white female virtue.

And these narratives are rooted in the Victorian understandings of gender and sexuality, but they're upheld by a number of Christian narratives. In many Southern communities, any kind of sexual relationship between a black man and a white woman is just called rape. There’s no conception of there being a possibility of a consensual relationship between a black man and a white woman.

And when Ida B. Wells says, “No one believes the threadbare lie that that black men rape white women in these alarming numbers,” she gets threatened with lynching as a result of saying that because in the social imaginary, there is no place for that kind of relationship ever being consensual.

She writes a bunch of editorials, naming specific cases where you have a relationship between these two, and once it's discovered, often the woman will say, “He raped me” to essentially to protect her own social status. And then he's killed. And that happens over and over and over again.

When people justify the practice of lynching, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th century they say, we only do it because of this crime of rape. But this narrative about this only happening because of sexual assault is demonstrably false. And these myths have so much social power to the extent that they keep people from resisting lunching in any significant way.

If the white women's virtue or purity was by far and away the main thing that drove lynchings a century ago, what would you say is the modern-day parallel to the lynchings taking place today? What would you say is driving the extrajudicial violence we’re seeing toward African Americans now?

Malcolm Foley: Women's virtue was a smokescreen for essentially keeping black communities in their place. Lynching is the most violent and public instantiation of white supremacy in American history because that’s its purpose. It’s purpose was essentially to terrorized communities into remembering they're in the second class.

When we think about today, and what the women’s virtue equivalent would be, fundamentally it comes down to the fact that while the practice of lynching has faded, the narratives that undergird people's willingness to believe in this idea of black criminality didn’t change. There's still the assumption that if you're a black man running in a neighborhood, there are some people who are going to think it is more likely for you to be a criminal than if it were a white man or white woman running.

There's something about these narratives of black criminality that we imbibe so constantly that it affects our unconscious judgment. And because of that, it often leads to death. And that is an infuriating reality and it's a lamentable reality.

Let’s talk about theological impact that lynchings end up having. How would you say they shaped both black church theology and white church theology?

Malcolm Foley: Lynching is an opportunity for specifically black churches to ask the question, what is the church? What does the church do? Because there's the assumption that we've got to do something. And you have a range of responses, but fundamentally they come from a place of recognizing human dignity and thinking through how to protect my brothers and sisters.

For a number of white churches, the toolkit remained largely in looking at the resources of the Constitution and things like that. So the critique of lynching rarely moved beyond “Lynching is anarchy, and we need to kind of reinforce the rule of law.” That's the most common anti-lynching rhetoric that you hear coming out of coming out of white churches. People were less willing, at least historically, to think through it in theological terms.

You’ve said that you really want white Christians to read texts from the black church, to read about the black church, and to view its story as family history. Can share how you imagine that happening and also what that has meant for you as an African American to also view the white church as your own family history?

Malcolm Foley: As someone who is deeply reformed, as someone seeking ordination in the PCA, as somebody who believes that the Westminster confession and standards are a faithful understanding of scripture, here's the answer that I would say to what that means:

It means that we have to expand the resources that we use both theologically and in terms of Biblical interpretation. So we got to expand the commentaries that we read, we've got to consider the range of Biblical interpretation from racialized minorities. It requires us to remind ourselves that we are not only neighbors, but also brothers and sisters in Christ and are worthy of being treated as such.

It means that when your brother or sister suffers, you've got to feel that suffering. You got to sit with them. That you don't feel like you have to speak because chances are, we're going to say the wrong things. It’s an opportunity for us to sit and learn from one another's experiences, to wrestle with how to apply the truth of the scriptures in not only our individual lives but in the spheres in which the Lord has placed us.

It means that means that the suffering of Christians around the world is our suffering. And it means that we've got to feel it and we're called to resist it. Because it extends beyond just loving our brothers and sisters in Christ, it extends to all of our neighbors, every other human being. And so alongside our evangelism, we also seek to alleviate one another’s suffering.

One of the things that's frustrating about, particularly about this history is that a number of black Christians feel like they have had to fight this battle alone because people have found excuses to not link hands with one another. And so it's my hope and my prayer that that happens before the Lord returns.