I squeeze into the middle airplane seat, politely apologizing to the person who got up from his aisle seat for me to get in. As I set my backpack down, trying to decide whether to grab my noise-canceling headphones, I greet the older woman in the window seat next to me. I opt for my book, kicking my backpack under the seat in front of me. Seat belt buckled, I settle in for my final flight of the day, hoping to making a dent in the chapter that awaits me.

“You from Nashville?” the woman asks.

“No, ma’am,” I reply. “I’m from Colorado Springs. I’m heading to Nashville for a conference.”

She smiles and nods. We both look away. I fiddle with my book; she returns to her crossword. I feel like I should return serve and ask her about where she’s from. She fills in the requested details, and I’m quite sure all the required talking is now complete.

Then she asks the question. “So, what do you do?”

I sigh, not audibly, but certainly in my heart. I should have grabbed my headphones, not my book, I think.

I briefly contemplate a generic answer, knowing the mere mention of my vocation can be a real conversation-stopper, but opt instead for the truth.

“I’m a pastor.”

She breaks out into a grin. “I knew it!”

“Really?” I am genuinely surprised.

“Yes!” she says with a knowing nod and a confident smile.

“How … ?”

“You just have the look.”

I laugh, briefly considering my wardrobe selection: blue jeans, high-tops, a black T-shirt, and an olive bomber jacket. Yeah, maybe I am a bit of a cliché at the moment.

As the smiles fade, I can’t help but wonder: I look like a pastor? Should I take that as a compliment?

Then I glance over at her crossword puzzle—it’s Bible trivia.

Ah. She meant it as a compliment. I think.

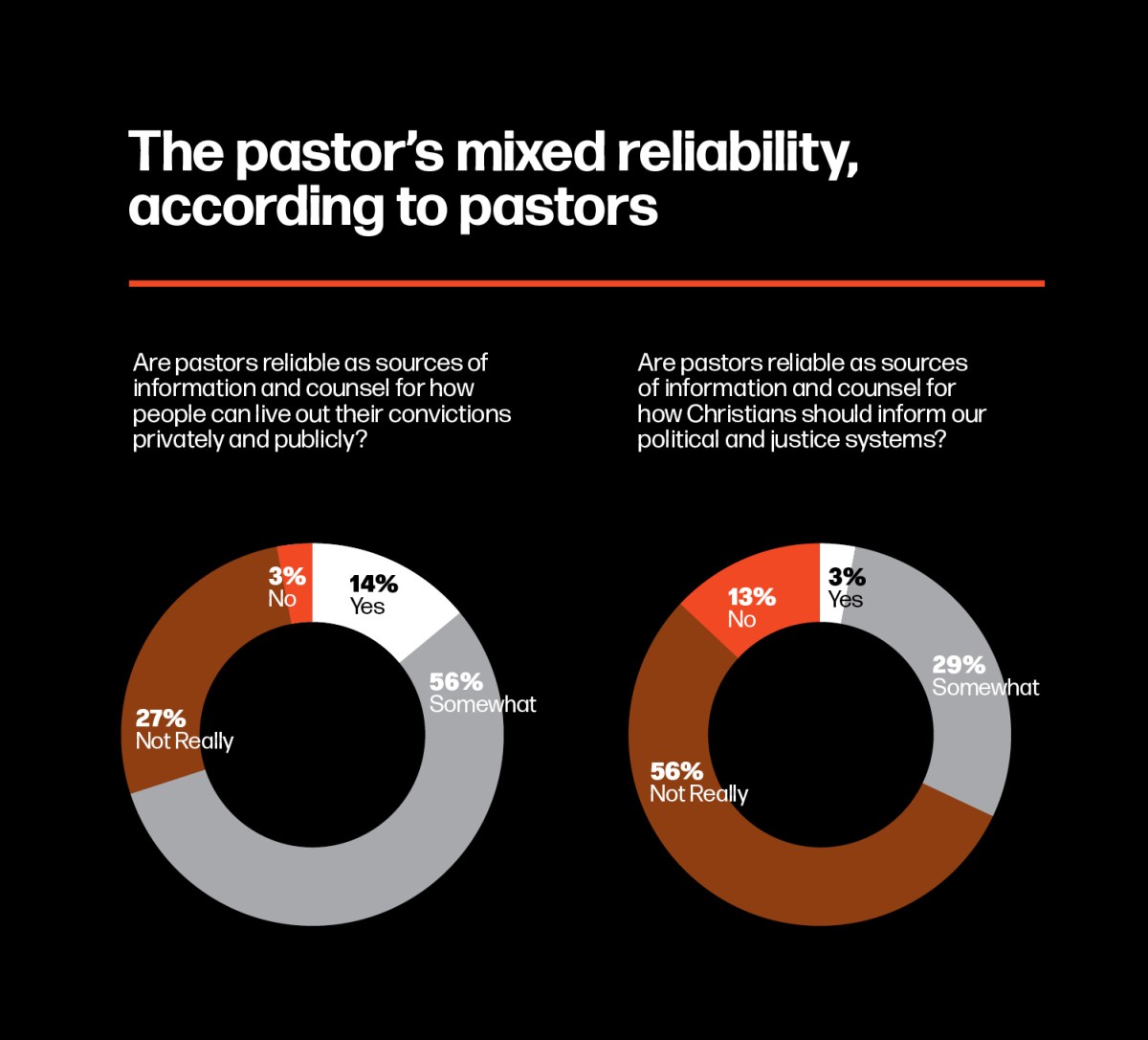

A bleak picture

Pastors do not hold the place of community esteem they once did. According to Barna’s State of Pastors report (2017), only about one in five Americans thinks of a pastor as very influential in their community, and about one in four doesn’t think they’re very influential or influential at all. The truth is, influential or not, many Americans don’t want to hear what pastors have to say. In 2016, Barna found that only 21 percent of Americans consider pastors to be “very credible” on the “important issues of our day.” Even among those Barna defined as evangelicals, the number only rises to slightly over half. Think about it: Nearly half of American evangelicals don’t see their pastors as being an authoritative voice for navigating current affairs.

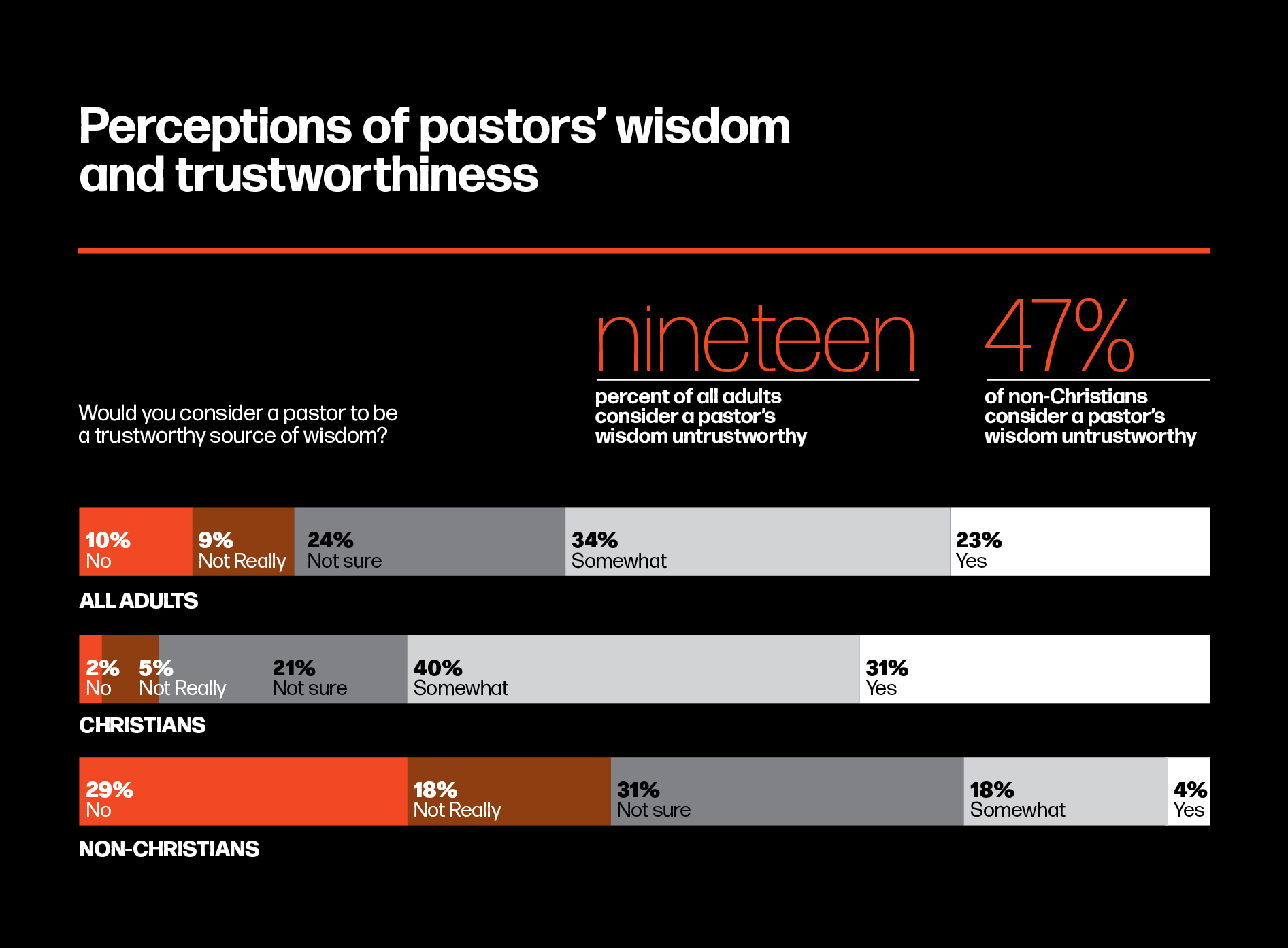

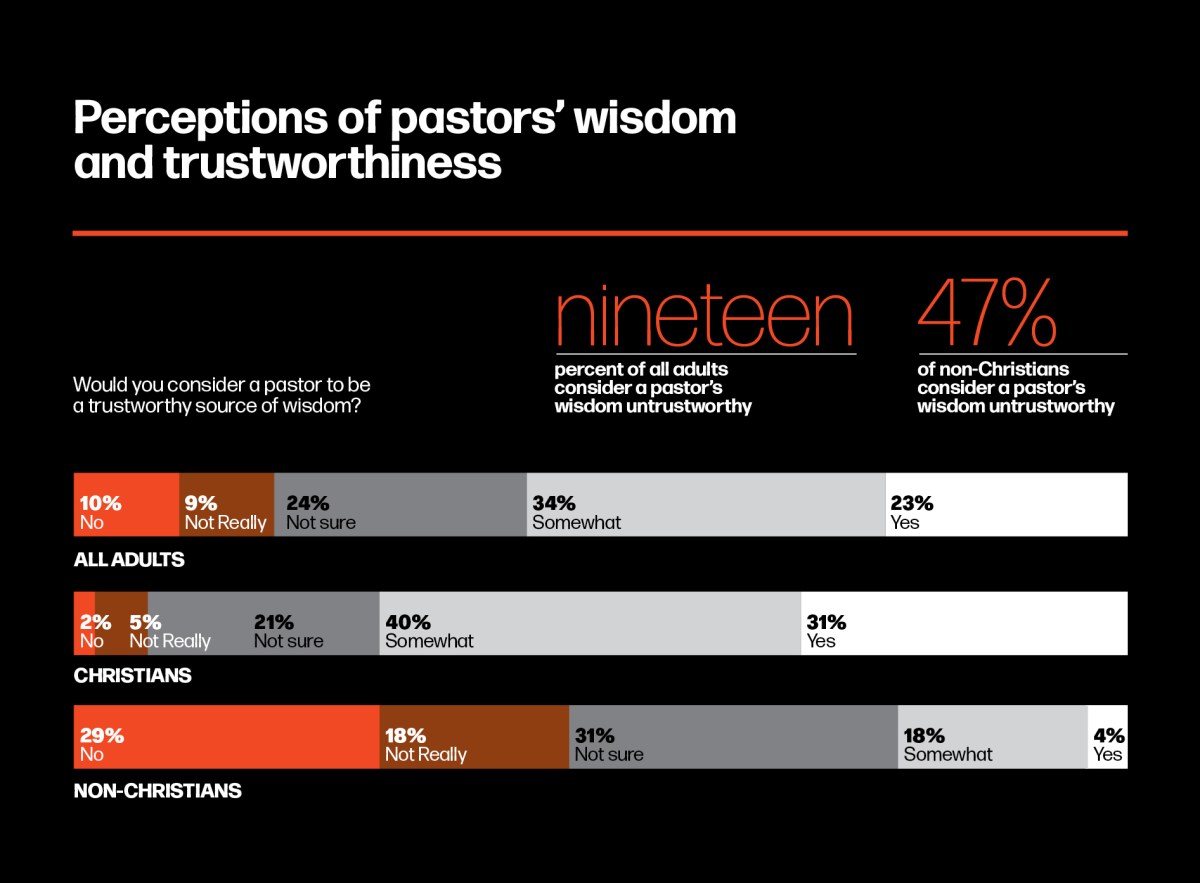

In a new study Barna and I did in 2020 for my book The Resilient Pastor, we learned that the picture might be getting worse. Only 23 percent of Americans said they “definitely” see a pastor as a “trustworthy source of wisdom.” Even among Christians, that number only rises to a mere 31 percent. Less than a third of Christians said they “definitely” consider a pastor a “trustworthy source of wisdom.” As you might expect, a mere 4 percent of non-Christians think of pastors in this way. That’s a pretty bleak picture.

Living in a digital age has added further complications. In one sense, the internet has been a great equalizer, disrupting traditional hierarchies of power and granting anyone the access and the potential to amass a following. Anyone can post; anyone can search; anyone can learn. The access to information has had a democratizing effect, so much so that authoritarian regimes around the world implement heavy-handed censorships and firewalls.

But access to information is a double-edged sword. It does not simply tear down or destabilize existing structures of authority. It creates new ways of establishing authority and gives rise to new authority figures, like Instagram influencers, bloggers, videos, and memes floating around Facebook. And with new “leaders” come new “tribes.” This can lead to the dangerous assumption that all views are equally valid. Each person becomes their own arbiter of religious truth, each doing what is right in their own eyes—or in the eyes of the podcaster they listened to this morning.

The invitation

It would be tempting to focus on how pastors can regain credibility. There is, of course, a need for that. Taking our vocation seriously means recognizing the weight of our words, the sacred nature of our duties, and the importance of a life of integrity. The declining credibility of pastors is bad news for the church. If we are going to invite anyone to follow us as we follow Christ, we have to work to regain the trust of reluctant followers. It will mean doing the right thing for the right reasons for a really long time.

All of that is true. But it’s important that we don’t rush to “fix” this. We have the opportunity to recognize the invitation in the midst of this—a phrase my spiritual director has used with me multiple times when I’m faced with a situation I don’t like, especially a situation beyond my control. Here in the aftermath of the storm, we hear the whisper of the Spirit’s invitation—an invitation, I suggest, shaped by three words: responsibility, accountability, and humility.

Responsibility. I am less interested in finding ways to regain our credibility than I am in our willingness to take responsibility for why we’ve lost it. We must face the reality that we have contributed to the crisis of credibility. Yes, there are cultural headwinds that have changed the social standing or cultural power of a pastor. But we have made a mess of things too. From small country churches to uber-megachurches, many pastors have been found to be bullies and hypocrites, alcohol abusers, and womanizers. The crisis of credibility is a symptom. The misuse of authority is the root cause.

The Old Testament reflects on the use of power in the way it tells the story of Israel’s first king. Saul’s story reveals three classic ways of mishandling authority: using it for our own benefit, overstepping the bounds of our authority, and exercising it rashly.

The prophet Samuel warned that a king takes (1 Sam. 8:11–17). How have we taken from our people? How have we taken their time, their hopes, their trust, and used it for our own ends? Maybe we have treated good-hearted people who serve our churches as though they are cogs in the machinery of our ambition. We are all too willing to take their time but slow to give ours.

As king, Saul infamously decided to act like a priest and offer sacrifices, overstepping the bounds of his authority (1 Sam. 13). In an attempt to be strong leaders, we can step into roles for which we have neither the training nor the calling to perform. For example, if we speak dismissively of mental health, saying from the pulpit that a person who is anxious simply needs to pray more, we erode our own credibility by overreaching with our authority.

Saul also used power rashly. After winning a battle, Saul ordered that no one eat anything, vowing to kill anyone who did (1 Sam 14). His own son unwittingly put his foolish vow to the test. How often do pastors cash in the capital of a congregation’s trust by calling them into a culture war? We announce with certainty whose “side” God is on, and in doing so we smear God’s name and diminish our credibility.

Misusing authority in this way may not be a problem for every pastor. But we can all take a hard look at ourselves and ask the Lord what measure of responsibility we must take for the loss of credibility among pastors.

Accountability. The decline in credibility means that very little will be handed to us. People are going to fact check our claims and compare our exegetical conclusions. But that can be a good thing. If we’ve done our homework, it will show. And if we’re shooting from the hip, they will likely know.

When a major social issue arises, it’s only a matter of time before someone posts on social media what pastors should say about it that Sunday. If your pastor doesn’t speak out about _____, then it’s time to find a new church, we are told. The media and the mob set the criteria for what a pastor should or should not say. Either way, the pastor is no longer the locus of authority or credibility.

I’m not a fan of this development. I don’t like pastors responding to pressure from a trending topic on Twitter. But there is also an opportunity here to accept accountability in this new age of visibility. The invitation in declining pastoral credibility may mean a move toward greater transparency. For example, how can we show the church the way their giving is being spent? How can our time and energy be held in check? If taking responsibility is about confession, embracing accountability is about changing our ways.

There’s one more word …

The source and the shape

Humility. That’s the final word to shape our response. Above all, the crisis in credibility should lead us to our knees. We should humble ourselves and return to the source of our authority.

During the Medieval centuries, a pastor—the priest—was a person who had been anointed with seemingly special powers. They could heal the sick through prayer and anointing with oil, hear from God and interpret the Scriptures, and turn bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ.

But as reformations led to rationalism, the pastor in the post-Enlightenment West found authority in his learning. Andrew Root in his book The Pastor in a Secular Age maps the shift in perceptions of pastors in America, noting that “the pastor no longer had magical powers, but he could read; he was no longer a superhero but now was just a learned man.” Jonathan Edwards, for example, devoted himself to study for 13 hours a day! This began a long tradition of education—the right seminaries and the right degrees—as the basis for credibility.

But Root notes another shift that began in the late 20th century: The authority of pastors began to come from the institutions they created. “Just as a CEO has the power of her office due to the societal or economic strength of the company, so too the pastor’s power depends on the size and influence of the congregation.” With long sermons potentially seen as a detriment and seminary education as a potential liability by some, pastors began to seek other ways of establishing their presence in a community. The answer was in building strong and influential churches.

But none of those things is the actual source of our authority. The source of our authority, ultimately, comes not from our popularity or influence (though without influence, one could hardly be a leader), not from our education (though training and preparation is a good thing), and not from the institutions we lead (though creating institutions is part of having presence and place). The source of our authority is Jesus, and it comes from being in his presence.

But that is not all. By being with Jesus, we learn from him what power is for. We rethink how our authority is used.

Jesus, “knowing that the Father had given all things into his hands, and that he had come from God and was going back to God” (John 13:3, ESV), got up, removed his robe, took up a towel and a basin, and began to wash the feet of his disciples.

Jesus knew where he had come from and where he was going. Jesus had been with the Father and was going back to the Father. Jesus knew that the mission and the ministry were what the Father had entrusted to him. And so he took the form of a servant and washed their feet. When you know the source of your authority, you understand the purpose for it.

Pastors, if our authority really did come from our education or the size of our institutions or the scope of our influence, then we could boast in it. We did this. We earned this. We worked for this.

But if we recognize it as a gift, if we understand that the only authority we have is that which comes from the anointing of the Spirit of the Lord, then that same Spirit works to form Christ in us.

The source of authority determines its shape. Our authority comes from Jesus, and it is to be used as Jesus used his power: to empty ourselves in service and self-giving love. As Paul would later write—paraphrased in The Message—our “strength is for service, not status” (Rom. 15:1). To recapture this perspective is to begin to return to credibility before Christ and his church.

Credibility is the result of the good and right stewardship of power—stewardship that understands the purpose of your power and the limits of your authority and acts accordingly with humility.

Responsibility. Accountability. Humility. I cannot promise that it will help us regain credibility. But it will, by God’s grace, make us more like Christ.

Glenn Packiam is associate senior pastor at New Life Church in Colorado Springs. He also serves as a senior fellow at Barna Group and an adjunct professor at Denver Seminary. His latest book is The Resilient Pastor. Portions of this article are adapted from The Resilient Pastor by Glenn Packiam (Baker Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2022). Used by permission.

This article is part of our spring CT Pastors issue exploring church health. You can find the full issue here.