Are you sure that’s a good idea?”

That’s the most common response I get when I tell someone our church is hosting a Sunday school class on faith and politics this fall in the middle of the 2020 election season. We’re a growing, politically diverse congregation in the heart of downtown Indianapolis, so I understand the concern. Isn’t talking about politics a recipe for disaster? Won’t it just lead to division and disunity? Totally possible. But if we’re serious about discipleship and following Jesus in every area of life, we have to try. Politics can’t be off-limits when it comes to our formation as believers.

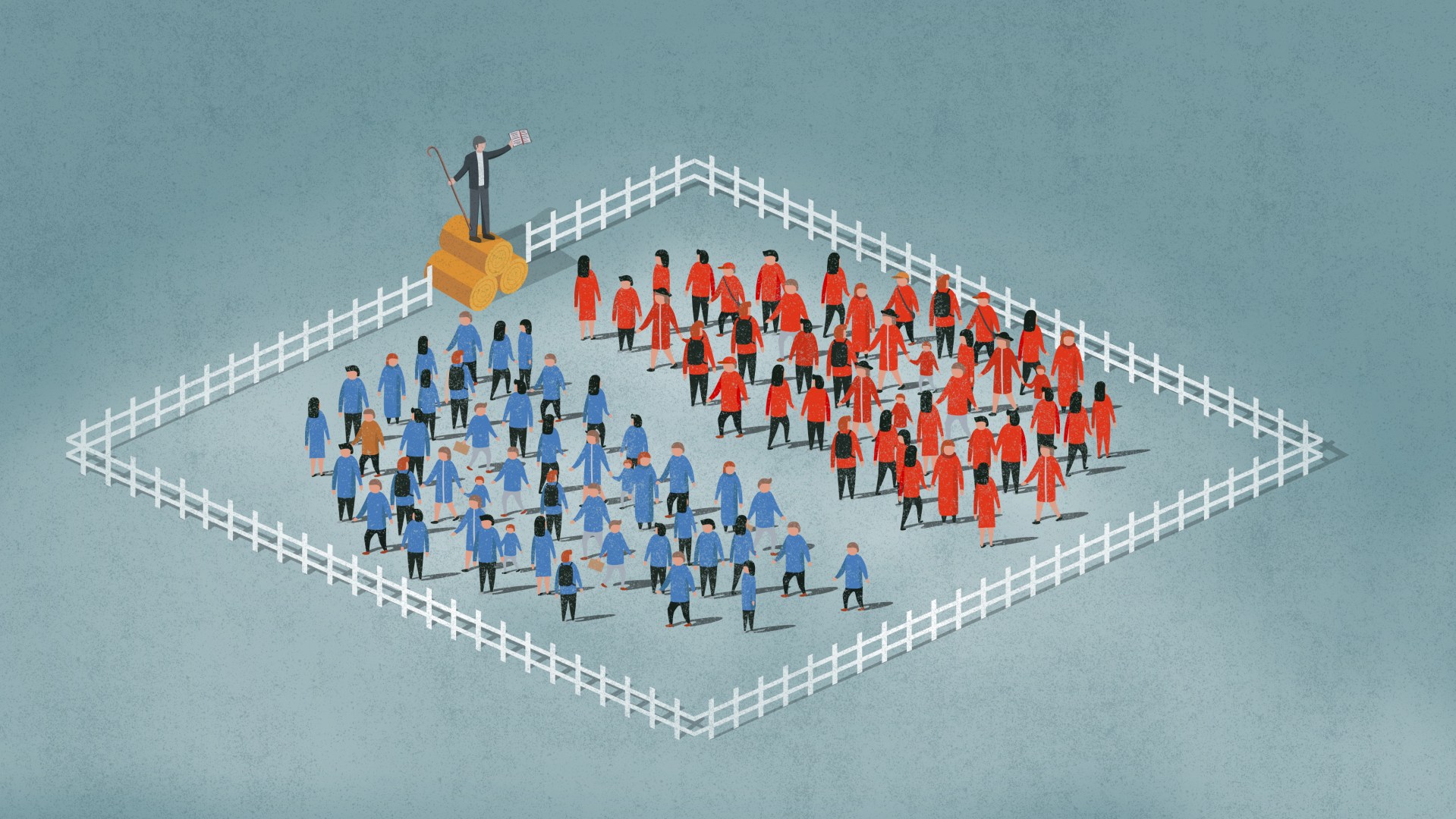

Name a topic and there are ready-made answers along partisan and ideological lines. From solutions to racial injustice to mitigating the spread of COVID-19, suspicion runs rampant. Hostility abounds. And in a climate like ours, many Americans are tempted—and taught—to believe the worst about their political opponents.

Almost 90 percent of Republicans say Democrats are “brainwashed” and “hateful,” and the numbers are even higher the other way around. Sadly, these dynamics are paralleled in the church. While we might hope to see more charitable conversations within the community of faith, a quick visit to Facebook reveals few discernible differences. In some ways, we shouldn’t be surprised. The average Christian spends an hour or two per week under the teaching of their local church but as many as 13 hours a day consuming other forms of media: listening to podcasts, scrolling through Twitter, watching cable news. How can we expect Christians to look any different when they’re functionally discipled by pundits and memes?

There has to be a better way.

Recent data suggest that US churchgoers generally don’t know the political leanings of their church leaders. Apart from certain high-profile examples to the contrary, the majority of pastors I know have little interest in endorsing candidates or telling their congregations exactly how they ought to vote—legally, we can’t, and most would be opposed as a matter of principle. Still, as Esau McCaulley highlights, the weightiest political claims are also ultimately theological, which means politics and faith can’t be neatly sealed off from each other. The New Testament itself is surprisingly rich with instruction on the relationship between faith and public life, often in contexts hostile to the church (Matt. 5; 1 Peter 2, Rom. 12–13; Rev. 13).

If discipleship is about following Jesus with all of our heart, soul, mind, and strength—a wholehearted commitment of all we think, do, love, and say—shouldn’t this include our politics as well? If believers are being formed by radio hosts and news programs, pastors must bear at least some burden to speak to these things too.

It’s commonplace for churches to devote great attention to helping believers consider how to follow Jesus in marriage, as a student, as a neighbor, or in the workplace. Pastors understand that unless people know God’s Word and can apply it in each of these areas, a litany of voices will end up filling in the void. Yet this kind of teaching is often strangely absent when it comes to political engagement. I’m not suggesting that churches start producing voter guides or using the pulpit for point-by-point policy analyses (probably best to leave that to the experts). I’m talking about giving people a framework for engaging politics biblically. For example:

- How do we honor God in the ways we think and act politically?

- In what ways might politics serve as a means of loving our neighbor?

- What does God’s Word have to say about justice, human nature, or the role of civil authority, and how should we apply it to the questions of our day?

- How do believers maintain unity and love in the midst of deep disagreement about real, significant issues?

None of these questions are simple, and faithful believers will come to various conclusions. Still, questions like these help us cut through the fog of partisan bickering and invite us to reckon with deeper matters of Christian fidelity. At its core, a Christian approach to politics is about asking, “What is God’s vision for a good and just society, and what must we cultivate in order to move in that direction (however imperfectly)?” That’s not to say our answers shouldn’t translate to genuine convictions about policy preferences—they should. But before we get to parties and platforms, political activity is about life in community.

As Vincent Bacote asks in The Political Disciple: “If Christ is being formed in God’s people by the Holy Spirit, has his work penetrated to those regions of the heart that reveal themselves in the domain of public responsibility?” While talking about politics is often fraught with difficulty, our political engagement is a matter of public holiness, Bacote says. Churches can and must lead their people in considering what this looks like. I’ve found three guidelines to be especially helpful.

Don’t shy away.

As tempting as it is to avoid the topic altogether, the need for wise, gracious, Christ-centered voices is difficult to overstate. If you’re not sure where to start, consider preaching a sermon or two about how the gospel might shape our political involvement. The Center for Public Justice has developed an entire small group curriculum that provides a theological basis and practical approach to active Christian citizenship. Similarly, our class will focus on key biblical texts and themes while also exploring major civic questions in the history of the church. Resources abound, and the possibilities are many. Whatever route you take, the dangers of disengagement far outweigh the benefits—especially in the long run.

Focus on principles before policies.

While there are certainly times for the church to take a clear moral stand, pastors and other leaders must exercise care and self-awareness to avoid drifting to a place of partisan manipulation. One way to do this is by focusing on the issues behind the issues. How do we honor the image of God in every person? What does it mean to “do justice” and “love mercy” in the communities God has placed us? How should the ninth commandment (you shall not bear false witness) impact our speech, media habits, and the way we interact with political sparring partners? The answers to these questions contain significant implications for how Christians can engage the political sphere without binding their consciences to a particular party or platform. Again, not all policies are created equal, but believers can differ when it comes to strategy and approach.

Finally, prioritize love.

G. K. Chesterton once quipped, “The Bible tells us to love our neighbors, and also to love our enemies; probably because generally they are the same people.” I’m convinced that learning to love our political enemies—no matter where you fall on the political spectrum—is among the most pressing issues facing Christians today. How do we engage from a place of love and not resentment? How do we relate to neighbors, family members, and others in our pew whose politics we find abhorrent (or at least troubling)? The answer, of course, looks a lot like crucifixion: taking up our cross, following Jesus, and pouring ourselves out for the good of those around us—even those who don’t think or vote like us. What better time to learn what this means for our politics than when we have to put it into practice?

Sam Haist is pastor of formation at Redeemer Presbyterian Church in Indianapolis.