Presbyterians And The Mainline Decline

The Presbyterian Presence: The Twentieth-Century Experience,seven volumes, edited by Milton J. Coalter, John M. Mulder, and Louis B. Weeks (Westminster/John Knox Press). Reviewed by Mark Noll, McManis Professor of Christian Thought at Wheaton College in Illinois.

This seven-volume series is the most comprehensive, the most honest, and the most illuminating study of an American denominational family ever published. The first six volumes present 60 essays by nearly 70 scholars, pastors, and denominational officials, which examine almost all imaginable aspects of the Presbyterian church in the twentieth century—from controversial decisions of general assemblies to the theological textbooks at seminaries; from lay attitudes toward Sunday to the participation of Hispanics, African Americans, Koreans, and native Americans in Presbyterian organizations.

The seventh volume, The Re-Forming Vision ($16.99), is a sustained argument from the three series editors, all of whom are associated with the Presbyterian Theological Seminary in Louisville. It attempts the daunting challenge of summarizing the findings of the previous six books, while also offering Presbyterians an agenda for the future.

The books treat most thoroughly the larger northern and southern Presbyterian churches, which in 1983 overcame regional differences dating back to the Civil War and united as the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) (PCUSA). Yet considerable coverage is also afforded the many smaller Presbyterian denominations, some of which have exerted an influence larger than their size.

More than just Presbyterian history, this series, appearing in the early 1990s, also addresses, by the nature of the case, the current predicament of the other mainline Protestant traditions.

Also reviewed in this section: Descending into Greatness, by Bill Hybels;The Women’s Bible Commentary, edited by Carol Newsom and Sharon Ringe;Dorothy Carey, by James Beck;The Son of Laughter, by Frederick Buechner.

What is Presbyterian?

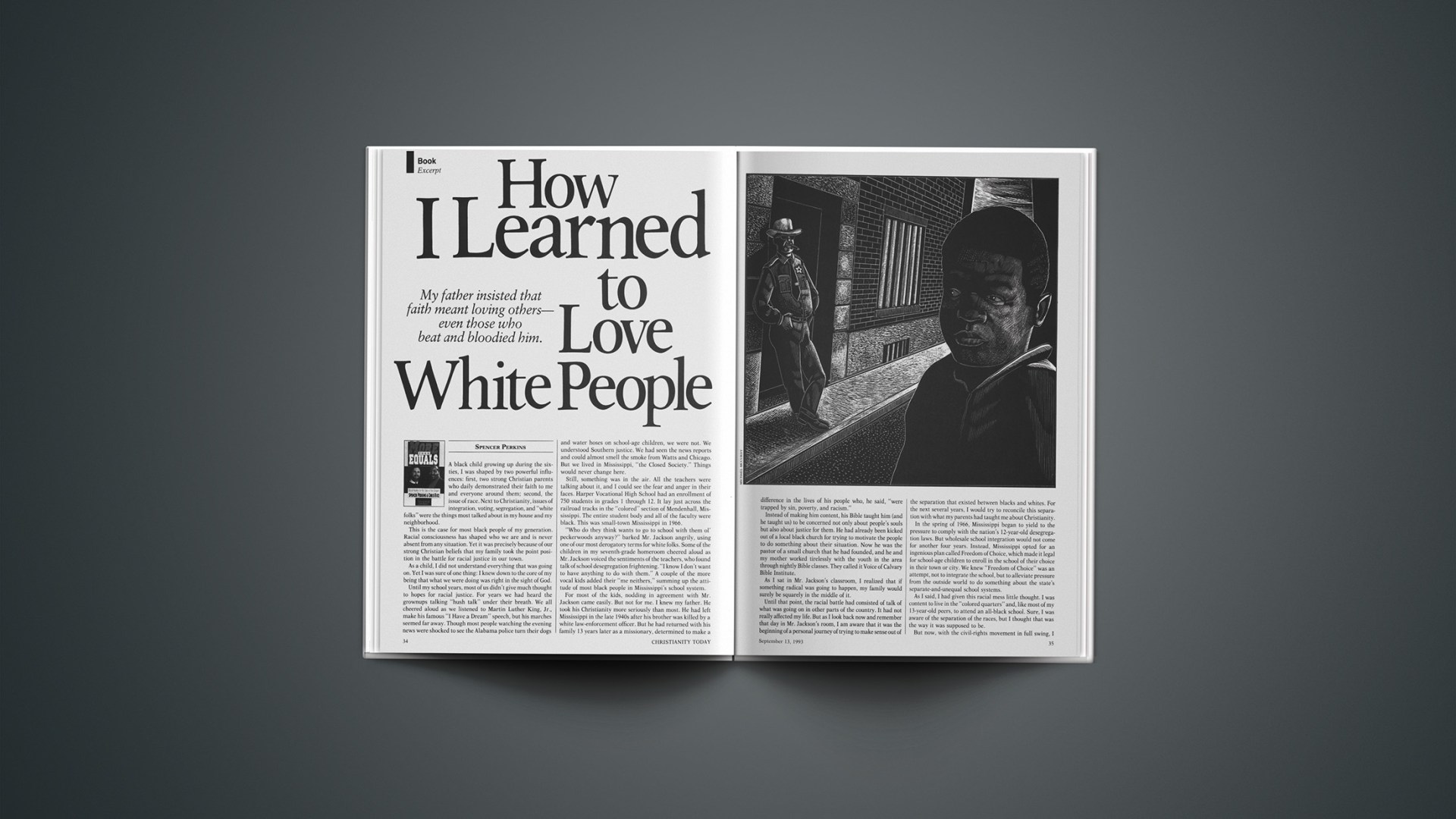

The editors are frank about the crises that afflict their denomination. Presbyterians have experienced dismaying numerical fortunes. From 1965 to 1990, the PCUSA—with its two predecessor denominations—experienced a decline in members from 4.25 million to 2.85 million. If absolute decline continues on that scale, this denomination will be extinct by the middle of the next century. (While some smaller Presbyterian denominations have grown rapidly in recent decades, all of them combined enroll less than one-seventh the members of the PCUSA.)

The editors deserve credit for their realization that a decline in membership, taken by itself, can never be the final word for churches that remember the Scriptures’ words about Christ’s “little flock.” Quite properly, therefore, they consistently move the discussion beyond quantity to questions of quality.

On that level, the books document a recurring confusion over identity. Thus, J. W. Gregg Meister accounts for failure to mount a sustained effort in the modern mass media by noting, “[Presbyterians] seemed reluctant to frame a message that was distinctly and identifiably Presbyterian.”

The editors’ reflection on twentieth-century history leads to the same conclusion. After disruptive controversies over doctrine earlier in the century, the church avoided doctrinal questions. The editors argue that “the fundamentalist controversy prompted the [main Northern church] to strip the denomination of its ability to define its faith, by lodging theological authority in the presbyteries.” The loss of theological identity went hand in hand with meandering in Christian practice. In a moving article on the decline of Presbyterian Sabbath observance, the sociologist Benton Johnson concludes, “The erosion of Sabbath observance is not only a paradigm of the erosion of faith in general, it is also a paradigm of the loss of spiritual practice in the mainline churches.”

It is entirely appropriate that several of the contributors emphasize the battles over doctrine of the 1920s and 30s as a key to the identity crises that followed for all Presbyterians. In that strife, confessional conservatives, led by J. Gresham Machen, challenged the denomination to reassert its historic doctrinal standards. The main Presbyterian churches chose, by contrast, the path of moderate inclusivism. The resulting schism was small, with only a few thousand leaving the Northern church to found new denominations under Machen’s inspiration. But the psychic-theological legacy was great.

The great tragedy of these battles was to make it extraordinarily difficult for Presbyterians of all kinds to inhabit the “middle” from which their predecessors had spoken powerfully in American culture. The “confessionalists” who broke away from the main Presbyterian church in the 1930s (as well as breakaways who have followed at regular intervals since) betrayed an extreme fear of appropriating anything from the “moderates” for fear of being labeled “liberals.” The “inclusivists” who remained in the large denomination betrayed an equally extreme fear of appropriating anything from the “conservatives” for fear of being labeled “fundamentalists.”

For the main Presbyterian bodies, the consequence of this theological paralysis has been drift. Stultifying preoccupation with procedure advances alongside the mushrooming of professional bureaucracy. Massive quota-think has replaced creative interaction with the Presbyterians’ historic confessions. Without an energizing theology, Presbyterians have maintained a nearly fatal commitment to the bankrupt assumptions of nineteenth-century “Christian America”—that is, to the notion that the conventions of the prestigious universities and the central values of the nation’s cultural arbiters provided standards to which the churches should conform.

Diagnosis or autopsy?

Although the editors are magnanimous denominational loyalists, they are not hesitant about prescribing a foundational remedy for the Presbyterian malaise. The prescription they offer is presented with great respect for the labors of twentieth-century Presbyterians. But it is also a prescription emphasizing a historic, rather than a modern, antidote. The tone of their appeal is well-illustrated by their words on the key issues that have always defined Christian churches:

Repentance: “Repentance will mean confessing that we have distorted the meaning of the Christian faith and the church’s mission.”

Faith: “In recent American Presbyterian history there has been a confusion about the primacy of faith in the Christian life. Faith is not knowledge of either the Bible or Christian doctrine, although it obviously includes that. Faith is the experience of knowing God’s grace in Jesus Christ.”

God: “Any truly mainstream Christian community must have a plumbline. That center in the Reformed tradition is a radical devotion to a sovereign God.”

The jury is out on whether Presbyterians will be able to reverse their dramatic decline. But that is not the most important question raised in these books. The series is very good on some of the vital—but not ultimate—questions, like why churches grow and decline, or how Presbyterians interact with American culture. But especially in the editors’ own work, the most important question comes to the fore—Do the Presbyterians, speaking out of their experience of the gospel of Jesus Christ, have anything to say? How that final question is answered will determine whether this splendid series is an autopsy or a first sign of return to health.

Addendum: Robert W. Lynn, formerly senior vice-president for religion at the Lilly endowment, brokered the grant that made this project possible. It is the latest, and most impressive, evidence of how Lynn almost single-handedly rejuvenated engaged study of America’s historic Protestant denominations.

Dare To Descend

Descending into Greatness, by Bill Hybels and Rob Wilkins (Zondervan, 216 pp.; $17.99, hardcover). Reviewed by John A. Baird, Jr., adviser to the president, Eastern College, Saint Davids, Pennsylvania.

In this surprising book, Bill Hybels, senior pastor of the influential Willow Creek Community Church (with the assistance of journalist Rob Wilkins), presents the radical proposition that true greatness and joy come from embracing the twin paradoxes that the way up is actually down, and that greatness is not a measure of self-will, but rather self-abandonment to God’s will.

With the poetic Philippians 2 passage about Christ “emptying himself” as his springboard, Hybels sets off on a challenging and often poignant journey that brings us face to face with “servanthood,” “humility,” “obedience,” and a particularly profound glimpse of “joy.” The tough questions and hopeful answers which punctuate this journey emphasize Jesus’s “downward mobility” as a model for every Christian life.

Early in the book Hybels makes clear that God’s call to lose for his sake does not mean denial of legitimate human needs. But what are our legitimate needs? The conscientious believer, offers Hybels, must let God determine which needs are legitimate and which are peripheral to genuine discipleship.

Descending into Greatness is not all talk. Several real-life exampples of contemporahry individuals dramatize the scriptural teachings. We meet an 80-year-old woman who has spent most of her life serving on an Indian reservation, a successful businessman struggling with personal priorities in the high stakes world of finance, and a suburban doctor who journeys to a primitive hospital in Africa, among others. They show us both the ordeal and joy of the descent.

Overall, the book succeeds in making us examine ourselves. The enthusiastic Hybels does sometimes overuse the vernacular and is overly critical of the American Dream as the only cause of selfish living; but the perceptive Hybels understands that moving down is not easy nor reducible to a tidy formula.

Most interestingly, Hybels reveals the struggles in his own life, admitting the irony in the pastor of one of America’s most successful churches writing a book on downward mobility. But it is that very honesty and self-censure that makes Descending into Greatness all the more compelling.

The Gospel According To Feminists

The Women’s Bible Commentary,edited by Carol A. Newsom and Sharon H. Ringe (Westminster/John Knox, 396 pp.; $23, hardcover). Reviewed by Rebecca Merrill Groothuis, author of Women Caught in the Conflict (forthcoming from Baker).

In the words of the editors, “The Women’s Bible Commentary is the first comprehensive attempt to gather some of the fruits of feminist biblical scholarship … in order to share it with the larger community of women who read the Bible.” Actually, the WBC is in the tradition of The Woman’s Bible, which in the 1890s compiled comments from feminists on passages of the Bible which were of particular interest to women. The volumes share a number of interesting similarities.

In evaluating the WBC—and the genre of feminist biblical scholarship which it represents—several important questions arise: What motivates these scholars to study the Bible? What is their goal or objective in the interpretive process? What is their understanding of how gender influences biblical interpretation? Behind the answers to these questions lie basic assumptions about the nature of the Bible and of sexuality.

Inspired or sexist?

From Sarah Grimke in the 1830s to the early evangelical feminist biblical scholars in the first decades of the twentieth century, evangelical women leaders of early American feminism maintained that the Bible had been mistranslated and misinterpreted so as to appear to teach the subordination of women as a universal norm. This twisting of the true message of Scripture, they believed, occurred at the hands of men who approached Scripture from the premise that men are primary and women secondary. Male translators and interpreters with such a bias tended to find in Scripture what they expected to find. Nevertheless, evangelical feminists believed and taught that, despite its cultural context, the Bible does not teach male domination as a universal, God-ordained norm.

But beginning with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who edited and contributed to The Woman’s Bible (in two volumes, 1895 and 1898), a different stream of feminist biblical study developed. The hermeneutic behind this work maintains that the message of the Bible itself is tainted with the sexist views of the men who wrote it. The problem, therefore, is not merely one of male-centered translation and interpretation; rather, misogyny is inherent in the text. It follows that for the editors for both the old and new volumes, then, the Bible cannot be viewed as a wholly authoritative and infallible standard of truth. Rather, it contains some true and good insights, as well as some false and harmful ideas. It is up to the feminist critic to determine which is which.

So if the Bible falls short by feminist standards, why exert so much effort dissecting and discussing it? According to the editors of the WBC, “The Bible has been one of the most important means by which woman’s place in society has been defined”; therefore, the meaning of biblical texts must be assessed “from a self-consciously feminist perspective.”

Although the Bible is a cultural and societal force, for evangelicals it is also God’s infallible and authoritative word—every believer’s source of life and truth. Respect for the veracity and authority of God’s word is foundational to evangelical feminism, and this is what primarily distinguishes it from the theologically “liberal” feminist approach to Scripture, which is exemplified in the WBC.

As Sharon H. Ringe explains in her chapter on feminist biblical interpretation, “There is no single ‘correct’ or ‘acceptable’ way to work, but what should be kept in mind is that the various approaches [to biblical interpretation] yield different results or conclusions.” The purpose of feminist biblical studies—such as those offered in the WBC—is to reach an interpretation that reflects “the voices of poor women and rich women, white women and women of color, single women and married women, women from one’s own country and from other parts of the world, lesbians and heterosexual women.” The goal is not to capture the objective sense of the text, but to attain a subjective sense that resonates with the views and experiences of its female readership.

A pink-lettered Bible

Integral to the subjective, person-relative approach to biblical interpretation is the belief that there is a thoroughgoing difference between women’s and men’s approaches to Scripture and to spirituality. If men’s understanding of spirituality is fundamentally different from women’s, then a book written entirely by men—such as the Bible—necessarily will present only a male version of spiritual reality. In order to be compatible with women’s spirituality, such a document must be revised and reconceptualized from a women’s point of view. Women, therefore, must be “self-conscious about reading [the Bible] as women.”

The idea that men and women understand Scripture and spirituality differently can be held in various degrees of extremity. In moderation this notion is harmless and can even be helpful. Certainly, women bring to their understanding of the Bible some life experiences that are quite different from men’s experiences, and this can create some variations in the ways men and women tend to approach biblical material. But these gender differences are not so radical as to render men’s ideas about spirituality irrelevant to women, or vice versa. The human commonality between women and men, especially in the spiritual dimension, is far greater and far more fundamental than their differences, and it is to this basic human spiritual dimension that the Bible speaks.

The WBC offers feminist perspectives on a wide range of biblical material. It does not purport to be a complete commentary on the Bible, but is intended as an introduction to feminist scholarship on those passages that are deemed pertinent to women. Despite the subjective, gender-relative hermeneutic that undermines its foundations, the WBC offers some useful information. Of particular value are two chapters on women’s cultural roles in Old and New Testament times. An interesting, though exasperating, chapter by co-editor Sharon H. Ringe lays bare the interpretive issues at stake in feminist theology.

The WBC revises the Bible’s “moral of the story” at times. Thus, Eve is viewed as having done well in “choosing knowledge. Together with the snake, she is a bringer of culture.” And the Song of Solomon is deemed a defense of illicit love, or, at any rate, a love relationship that is “in contradiction to prevailing norms.” Other aspects of the commentary offered in this volume are an evolutionary and syncretistic view of the Hebrew religion, a questioning of the historicity of the biblical stories of Genesis, much questioning of biblical authorship, a general attitude of detachment from the religious convictions of the believers depicted in the Bible, and a willingness to explain apparently contradictory passages as, simply, contradictory.

William Carey’S Burden

Dorothy Carey: The Tragic and Untold Story of Mrs. William Carey,by James R. Beck (Baker, 254 pages; $13.95, paper). Reviewed by Karen K. Hiner, a writer living in Boise, Idaho.

Oswald Chambers said, “If we obey God, it is going to cost other people more than it costs us.” In his new biography of Dorothy Carey, James Beck demonstrates just how much one person’s obedience can cost another.

In 1793, William Carey volunteered to go as a missionary to India, becoming the “father of modern missions.” Beck believes that Carey’s is “one of the greatest of all modern missionary stories,” but that it “includes one of the most tragic,” that of his wife, Dorothy.

In 1786, an impassioned William Carey questioned the antimissionary attitudes of his day and formulated a new concept of world evangelism. Five years earlier, however, when Dorothy Plackett agreed to marry William, a 19-year-old shoemaker, neither had any idea they would give their lives for missions—he willingly; she unwillingly.

During the next 12 years, Carey evolved from shoemaker to pastor to mission enthusiast to mission appointee. During that same period, Dorothy gave birth to five children (two of whom died), maintained a home on their limited income, and watched her husband develop an unquenchable vision for reaching the lost in a land she knew nothing about.

When the Careys arrived in India, they moved often, usually living in unsafe surroundings. Within two years, Dorothy contracted a chronic physical illness, buried her third son, who died of dysentery, gave birth to another son, and subsequently lost touch with reality. Never recovering her sanity, she died 12 years later—in India. Apparently William decided not to return to England to ease her distress.

In this well-researched book, Beck seeks to correct the negative impression some of William’s biographers have given of Dorothy. One wrote, “Never had minister, missionary, or scholar a less sympathetic mate” who remained “a peasant woman with a reproachful tongue.” Beck suggests that Dorothy was criticized because she did not conform to the image of the compliant, long-suffering wife. On the other hand, William’s biographers glossed over his shortcomings and tendency to give priority to his missionary work at the expense of his family.

Beck’s new angle on the William Carey saga does not discount the man’s immense contributions to the modern missionary movement. Rather, Beck is attempting to counter the serious neglect many church historians have shown toward the important and often sacrificial role women have played in the spreading of the gospel. Beck’s Dorothy Carey allows us to consider more clearly the historically misjudged life of a woman who played a key role in the birth of modern missions.

Colorizing Jacob

The Son of Laughter,by Frederick Buechner (HarperSanFrancisco, 274 pp.; $19.00, hardcover). Reviewed by Virginia Stem Owens, the author of the mystery novel Congregation (Baker).

For centuries Scripture’s treasure-trove of stories has lured writers looking for material. The Old Testament in particular, with its tales of espionage, murder, war, adultery, incest, and even cannibalism, is crammed with enough sex and violence to give even Hollywood a run for its money.

Frederick Buechner is the latest novelist to take the bait. In The Son of Laughter he has Jacob narrate the family saga, from grandfather Abraham—“a barrel-chested old man with a beard dyed crimson”—to son Joseph, the dreamer-made-good in the Black Land, the clan’s name for Egypt.

Throughout, Buechner sticks amazingly close to the biblical narrative and does a masterful job of untangling the various snarls of events, deleting none of the difficult material. Not only is Buechner’s thorough treatment true to the text, but he also brings us an ancient world credibly outfitted, compliments of modern archaeological spadework. Details of tents, clothing, food, and nomadic technology supply the novel with the verisimilitude of a period-piece movie.

The Bible by Homer

Why then does this book, like every other Bible-based novel I’ve read, leave me feeling vaguely dissatisfied?

Perhaps Erich Auerbach answered the question 50 years ago in his book Mimesis where he contrasted the sparse Hebrew narratives with their Greek counterpart, the Homeric epic.

Homer set the standard for entertaining stories with his rich description of settings and characters. Biblical tales, in contrast, contain hardly any details about surroundings or motivation. The gaping holes in biblical narrative, Auerbach says, are meant to invite, even demand, interpretation.

Buechner, like many a novelist before him, sets out to fill those holes with ample Homeric description, description that inevitably becomes interpretation. Buechner supplies a motivation for Isaac mistakenly blessing the younger twin: he had an eating disorder—as Jacob explains: “We had already eaten well that day but my father took a charred gobbet of the venison that Esau had brought him and placed the whole of it in his mouth. He licked the fat off his thumb and forefinger. His eyes glazed over as he chewed.”

Even minor characters are filled out. Bilhah, Rachel’s maid who supplied a surrogate womb for her barren mistress, is described in detail: “She had large hands and feet. She had eyes that swelled in their sockets beneath the sweeping brows of an owl.”

Descriptions of God are harder to supply, of course. Unlike Homer’s Athena or Zeus, the Hebrew God can only be described by implication. Buechner relies on his nomads’ name for their invisible deity—“the Fear.” And so a pensive Jacob declares: “a god named is a god summoned. The Fear comes when he comes. It is the Fear who summons.… Trust him though you cannot see him.… Trust him though you have no name to call him by, though out of the black night he leaps like a stranger to cripple and bless.”

Meaningful gaps

Inevitably, however, filling the gaps of the biblical account turns the interpreter into the interpreted. For it is only with himself that any novelist—or preacher or reader for that matter—can plug those holes. Hence, Buechner’s Jacob sometimes sounds more like an Ivy League introvert than a preliterate patriarch. (The obsessive recording of scatological phenomena, especially, seems the product of New England squeamishness. To Mesopotamian migrants, surely excretion would be ordinary, and hence unremarkable.)

The Son of Laughter definitely succeeds in terms of entertainment and passionate narrative. Yet, like other novels borrowing from biblical stories, it simply fills in too much, closing the gaps which, Auerbach says, are intended “to overcome our reality.” Any reality we add will always be exasperatingly partial. Instead of explaining the biblical world in our terms, we must “fit our own life into its world” and allow ourselves “to be elements in its structure of universal history.” The gaps are meant to swallow us.