As speculation about a possible successor intensified in recent years, Billy Graham always told reporters that the decision was not his to make, but up to God and the 32-member board of directors of his Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA).

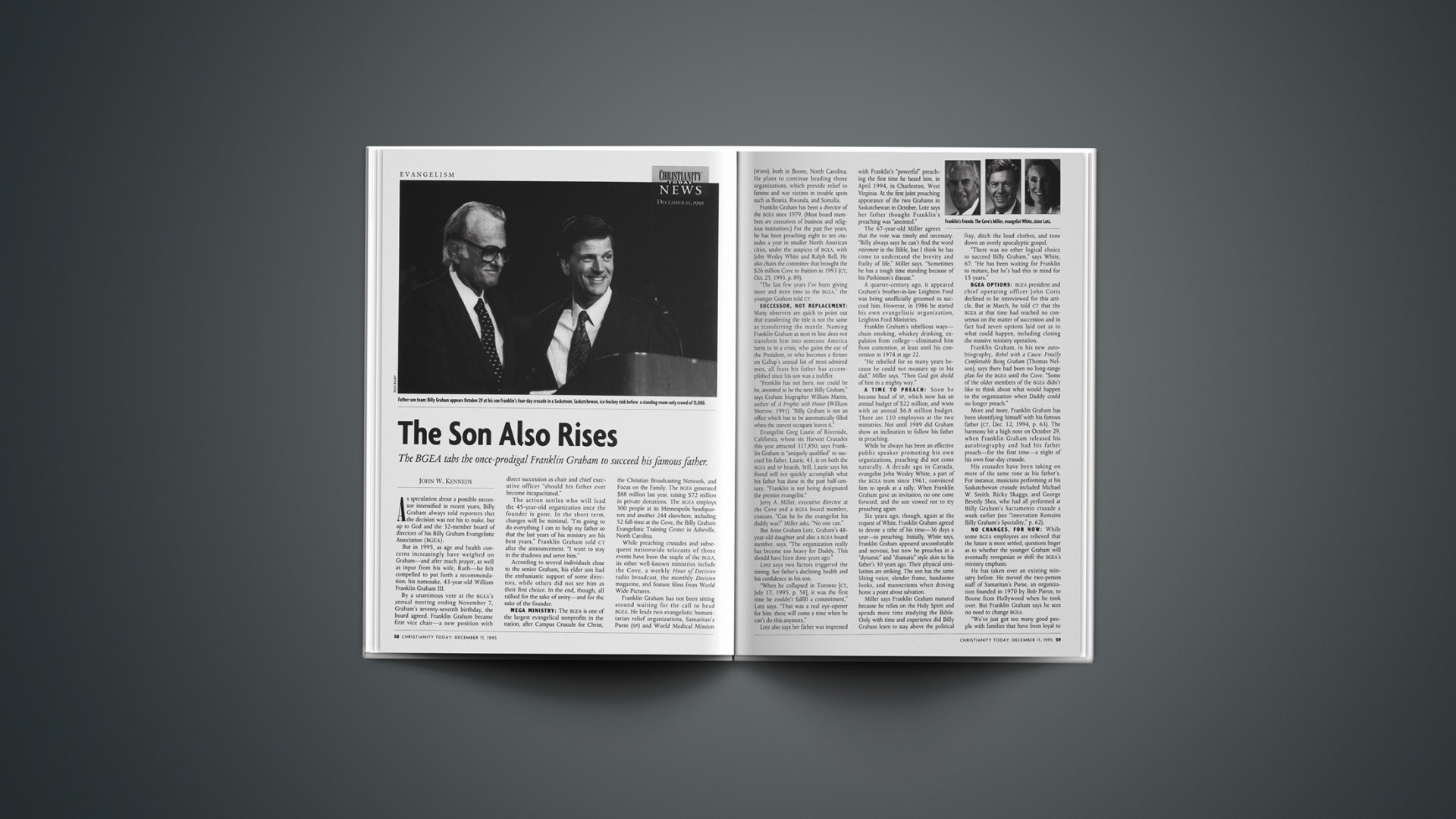

But in 1995, as age and health concerns increasingly have weighed on Graham—and after much prayer, as well as input from his wife, Ruth—he felt compelled to put forth a recommendation: his namesake, 43-year-old William Franklin Graham III.

By a unanimous vote at the BGEA's annual meeting ending November 7, Graham's seventy-seventh birthday, the board agreed. Franklin Graham became first vice chair—a new position with direct succession as chair and chief executive officer "should his father ever become incapacitated."

The action settles who will lead the 45-year-old organization once the founder is gone. In the short term, changes will be minimal. "I'm going to do everything I can to help my father so that the last years of his ministry are his best years," Franklin Graham told CT after the announcement. "I want to stay in the shadows and serve him."

According to several individuals close to the senior Graham, his elder son had the enthusiastic support of some directors, while others did not see him as their first choice. In the end, though, all rallied for the sake of unity—and for the sake of the founder.

MEGA MINISTRY: The BGEA is one of the largest evangelical nonprofits in the nation, after Campus Crusade for Christ, the Christian Broadcasting Network, and Focus on the Family. The BGEA generated $88 million last year, raising $72 million in private donations. The BGEA employs 300 people at its Minneapolis headquarters and another 244 elsewhere, including 52 full-time at the Cove, the Billy Graham Evangelistic Training Center in Asheville, North Carolina.

While preaching crusades and subsequent nationwide telecasts of those events have been the staple of the BGEA, its other well-known ministries include the Cove, a weekly Hour of Decision radio broadcast, the monthly "Decision" magazine, and feature films from World Wide Pictures.

Franklin Graham has not been sitting around waiting for the call to head BGEA. He leads two evangelistic humanitarian relief organizations, Samaritan's Purse (SP) and World Medical Mission (WMM), both in Boone, North Carolina. He plans to continue heading those organizations, which provide relief to famine and war victims in trouble spots such as Bosnia, Rwanda, and Somalia.

Franklin Graham has been a director of the BGEA since 1979. (Most board members are executives of business and religious institutions.) For the past five years, he has been preaching eight to ten crusades a year in smaller North American cities, under the auspices of BGEA, with John Wesley White and Ralph Bell. He also chairs the committee that brought the $26 million Cove to fruition in 1993 (CT, Oct. 25, 1993, p. 89).

"The last few years I've been giving more and more time to the BGEA," the younger Graham told CT.

SUCCESSOR, NOT REPLACEMENT: Many observers are quick to point out that transferring the title is not the same as transferring the mantle. Naming Franklin Graham as next in line does not transform him into someone America turns to in a crisis, who gains the ear of the President, or who becomes a fixture on Gallup's annual list of most-admired men, all feats his father has accomplished since his son was a toddler.

"Franklin has not been, nor could he be, anointed to be the next Billy Graham," says Graham biographer William Martin, author of "A Prophet with Honor" (William Morrow, 1991). "Billy Graham is not an office which has to be automatically filled when the current occupant leaves it."

Evangelist Greg Laurie of Riverside, California, whose six Harvest Crusades this year attracted 317,850, says Franklin Graham is "uniquely qualified" to succeed his father. Laurie, 43, is on both the BGEA and SP boards. Still, Laurie says his friend will not quickly accomplish what his father has done in the past half-century. "Franklin is not being designated the premier evangelist."

Jerry A. Miller, executive director at the Cove and a BGEA board member, concurs. "Can he be the evangelist his daddy was?" Miller asks. "No one can."

But Anne Graham Lotz, Graham's 48-year-old daughter and also a BGEA board member, says, "The organization really has become too heavy for Daddy. This should have been done years ago."

Lotz says two factors triggered the timing: her father's declining health and his confidence in his son.

"When he collapsed in Toronto [CT, July 17, 1995, p. 58], it was the first time he couldn't fulfill a commitment," Lotz says. "That was a real eye-opener for him: there will come a time when he can't do this anymore."

Lotz also says her father was impressed with Franklin's "powerful" preaching the first time he heard him, in April 1994, in Charleston, West Virginia. At the first joint preaching appearance of the two Grahams in Saskatchewan in October, Lotz says her father thought Franklin's preaching was "anointed."

The 67-year-old Miller agrees that the vote was timely and necessary. "Billy always says he can't find the word retirement in the Bible, but I think he has come to understand the brevity and frailty of life," Miller says. "Sometimes he has a tough time standing because of his Parkinson's disease."

A quarter-century ago, it appeared Graham's brother-in-law Leighton Ford was being unofficially groomed to succeed him. However, in 1986 he started his own evangelistic organization, Leighton Ford Ministries.

Franklin Graham's rebellious ways—chain smoking, whiskey drinking, expulsion from college—eliminated him from contention, at least until his conversion in 1974 at age 22.

"He rebelled for so many years because he could not measure up to his dad," Miller says. "Then God got ahold of him in a mighty way."

A TIME TO PREACH: Soon he became head of SP, which now has an annual budget of $22 million, and WMM with an annual $6.8 million budget. There are 110 employees at the two ministries. Not until 1989 did Graham show an inclination to follow his father in preaching.

While he always has been an effective public speaker promoting his own organizations, preaching did not come naturally. A decade ago in Canada, evangelist John Wesley White, a part of the BGEA team since 1961, convinced him to speak at a rally. When Franklin Graham gave an invitation, no one came forward, and the son vowed not to try preaching again.

Six years ago, though, again at the request of White, Franklin Graham agreed to devote a tithe of his time—36 days a year—to preaching. Initially, White says, Franklin Graham appeared uncomfortable and nervous, but now he preaches in a "dynamic" and "dramatic" style akin to his father's 30 years ago. Their physical similarities are striking. The son has the same lilting voice, slender frame, handsome looks, and mannerisms when driving home a point about salvation.

Miller says Franklin Graham matured because he relies on the Holy Spirit and spends more time studying the Bible. Only with time and experience did Billy Graham learn to stay above the political fray, ditch the loud clothes, and tone down an overly apocalyptic gospel.

"There was no other logical choice to succeed Billy Graham," says White, 67. "He has been waiting for Franklin to mature, but he's had this in mind for 15 years."

BGEA OPTIONS: BGEA president and chief operating officer John Corts declined to be interviewed for this article. But in March, he told CT that the BGEA at that time had reached no consensus on the matter of succession and in fact had seven options laid out as to what could happen, including closing the massive ministry operation.

Franklin Graham, in his new autobiography, "Rebel with a Cause: Finally Comfortable Being Graham" (Thomas Nelson), says there had been no long-range plan for the BGEA until the Cove. "Some of the older members of the BGEA didn't like to think about what would happen to the organization when Daddy could no longer preach."

More and more, Franklin Graham has been identifying himself with his famous father (CT, Dec. 12, 1994, p. 63). The harmony hit a high note on October 29, when Franklin Graham released his autobiography and had his father preach—for the first time—a night of his own four-day crusade.

His crusades have been taking on more of the same tone as his father's. For instance, musicians performing at his Saskatchewan crusade included Michael W. Smith, Ricky Skaggs, and George Beverly Shea, who had all performed at Billy Graham's Sacramento crusade a week earlier (see "Innovation Remains Billy Graham's Speciality," in this issue).

NO CHANGES, FOR NOW: While some BGEA employees are relieved that the future is more settled, questions linger as to whether the younger Graham will eventually reorganize or shift the BGEA's ministry emphasis.

He has taken over an existing ministry before. He moved the two-person staff of Samaritan's Purse, an organization founded in 1970 by Bob Pierce, to Boone from Hollywood when he took over. But Franklin Graham says he sees no need to change BGEA.

"We've just got too many good people with families that have been loyal to this organization, loyal to my father," he says. "I would never think of doing anything that would hurt that kind of relationship or that unity that we have."

He says he has the support of the BGEA board. "I'm sure there may be somebody out there that may not like me," he says. "If there's somebody who wasn't happy, they didn't say anything, and they were given plenty of opportunity."

At the November meeting, the founder told board members to propose a better plan, if anyone had one, and to wait until January to approve his recommendation. Miller notes the board decided to act immediately.

ALL IN THE FAMILY: "I think everyone in the family is very supportive," Franklin Graham says. "I don't know of any jealousies. I think they all have expected this for some time."

All four of his siblings are involved in ministry: Gigi Tchividjian, 50, an author and seminar speaker; Lotz, 48, founder of AnGeL Ministries in Raleigh, North Carolina; Ruth McIntyre, 45, a Samaritan's Purse employee based in Fort Defiance, Virginia; and Ned, 37, president of East Gate Ministries in Sumner, Washington, a missionary organization working in China.

Some observers say Lotz, a Southern Baptist itinerant preacher, is every bit as powerful as her father in his heyday.

"I'm not an evangelist," she says. "I'm not comfortable giving an invitation in a stadium.

"The BGEA call is on Franklin," Lotz says. "I believe I am called to teach and preach. I don't need the BGEA to do that."

FINANCIAL INTEGRITY: One of the hallmarks of the BGEA has been financial integrity. Graham's salary and housing allowance amounts to $135,000 a year. Since 1950 he has received no speaking fees or honorariums, and his book royalties have been placed in a trust that pays for ministry operations.

Franklin Graham's annual SP salary is $106,533, and for now he will not be added to the BGEA payroll. The Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability (ECFA)—the watchdog organization cofounded by his father—suspended SP and WMM in March 1992, citing "inadequate control." ECFA readmitted SP and WMM in January 1993 after receiving information on the cost of fundraising as a percentage of income; board approval for Graham's involvement in a charity event; and explanation of advance budgeting procedures.

Franklin Graham has denied any wrongdoing. "We never broke any laws, we never violated any standards," he told CT last year. "It took several months for us to be able to give all the facts and all the material for them to look at, and they were satisfied."

THE LESS-TRAVELED ROAD: Franklin Graham says he is content to continue preaching in less-populated areas, and he will reduce his number of missions conference and church speaking commitments in order to focus on crusades.

While Billy Graham's recent venues have included huge, domed stadiums in Tokyo, Toronto, and Atlanta, his son typically preaches in gymnasiums and auditoriums in places such as Bozeman, Montana, and Farmington, New Mexico.

"We've had great results in these mid-sized towns," Franklin says. "If doors open up in bigger cities, fine. But I'm not looking for it."

Both Grahams plan to preach in Auckland, New Zealand, in February and in Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane, Australia, in March.

Beyond that, Billy Graham is scheduled to preach only in June in Minneapolis, his BGEA base, and in September in his hometown of Charlotte, North Carolina. In the Sacramento crusade in October, he indicated the Charlotte event "may be the last crusade we'll ever hold like this."

Franklin Graham says, "If we get to September of next year and Daddy still has strength and health, we're going to go on. I'm going to be the first one to encourage him." By sharing some of the preaching, he believes his father's ministry may be extended. "As long as he can breathe and whisper the name of Jesus Christ, I'm going to say, 'Daddy, keep going.' "

Martin, Graham's biographer, says Franklin Graham faces a much more crowded evangelical field than his father did when he helped coalesce the movement. "It seems unlikely that mass crusade evangelism will ever have in this country the same kind of potential that it had in the 1940s and 1950s," Martin says. "There is now so much competition for the general public's attention and so many other avenues for evangelical Christians to carry out their missions than mass crusades."

Franklin Graham knows the comparisons with his father that he has dreaded over the years will only increase now. "I have not been asked to replace my father," he says. "If I had been asked to do that, I wouldn't, because I can't. But I have been asked to manage this organization and lead it. I'm committed to holding this organization together and keeping it in crusade evangelism."

Copyright © 1995 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

ctcurrmrj5TE0585B29