Hello, fellow wayfarers … Why “render unto Caesar” doesn’t mean what many have been taught it means, and how that affects our view of Election Day … What a social media post transformed in the way I watch Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas … How an old C. S. Lewis poem wrecked me this week … A Desert Island Bookshelf from the Land of Lincoln … This is this week’s Moore to the Point.

The Election Is a Coin Toss—in More Ways Than One

This column originally appeared in the Evangelicals in a Diverse Democracy series.

“Here we are, right at the end, and the election is a coin toss.” A friend said that to me just a few minutes ago, referring to the razor-thin polling margins between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris. A few thousand votes one way or the other in as few as three swing states could produce radically different alternatives for the future of the country.

I wonder, though, whether as American Christians we ought to think of Election Day as a coin toss in a different way as well. Even in a more secularized society, the words “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s” (Mark 12:17, ESV throughout) are still recognizable to most people. The account—from the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke—recounts Jesus’ response to the question of whether to pay taxes to the Roman emperor’s regime.

Like many other Scriptures, those words have been grossly misused. They’re quoted to justify churches engaging directly in political activism (often paired with a misreading of Abraham Kuyper’s famous declaration that there is not one square inch of the universe that Jesus does not claim as “Mine”). They are also quoted to make the case for a separation of Christian conscience from public justice (often with a similarly downgraded version of Martin Luther’s idea of two kingdoms).

Jesus’ words here actually speak sharply to what it means to be his follower in a time of pronounced divisions and high stakes. But to hear them rightly, we must pay attention to how Jesus discerned what was real and what was false. In many ways, his political situation—though radically different, set in an ancient empire rather than a modern democracy—was similar to the one facing us right now.

First, Jesus upended an artificial controversy to provoke a genuine crisis in his hearers. The question about taxes was posed by two very disparate groups—the Pharisees and the Herodians—but neither side was truly grappling with a theological dilemma. They were executing a strategy. They were humiliated by Jesus’ parables against them and so plotted “to trap him in his talk” (v. 13). This was a proxy war.

Jesus saw through the artificial controversy and the manipulative flattery with which it was framed: “Teacher, we know that you are true and do not care about anyone’s opinion. For you are not swayed by appearances, but truly teach the way of God” (v. 14). It was not out of naive ignorance but “knowing their hypocrisy” (v. 15) that Jesus answered.

What Jesus recognized here was what journalist Amanda Ripley calls “conflict entrepreneurs,” those who have an interest in creating havoc and division for its own sake. If we are to seek “the mind of Christ” (1 Cor. 2:5–6), we should likewise be able to recognize that often what really matters is not what’s debated most fiercely around us. Such controversies may light up the limbic system, but often they distract us from what really matters, to the detriment of our neighbors and ourselves.

As Jesus upended the artificial controversy, he also upended the tribalism that undergirded it. The conversation about Caesar’s coin, after all, was not really about tax policy. The Pharisees knew that the throne of the kingdom of Israel belonged by covenant to David’s heir (2 Sam. 7:1–17), not to a puppet of some Gentile occupying force. So if Jesus told his hearers to pay taxes to Caesar, he’d be understood as negating that covenant promise. But if Jesus had answered that people should withhold the tax, this would be heard as Jesus urging insurrection against Rome.

Those who were “just asking questions” knew that they could use the question—particularly for those who cared about God’s covenant—to draw tribal boundaries. For the whole crowd, they could make taxes into a “You’re not one of us” question of identity. They chose this strategy of riling political passions because they “feared the people” (Mark 12:12). To deny the possibility that Jesus was, in fact, “the stone that the builders rejected” (v. 10), now made the cornerstone of a new creation, they sought to push him into existing divisions.

The trap aside, those divisions were real and serious. So too are the divisions in American life—and the consequences of this election are of crucial importance. But one of the reasons the country is exhausted is that so much of our political debate is not about politics at all. It’s about whether one is really part of the tribe—whatever tribe that is. To be excluded feels like a threat to our very existence.

Yet Jesus refused to join a tribe and instead asked for a coin. In this, he reordered the priorities of the entire conversation. “Whose likeness and inscription is this?” he asked (v. 16). Caesar, of course, had honored his own image, depicting himself as the son of the gods.

Jesus’ response made all that self-magnified glory look pitiful and small. He tossed the coin back to his interrogators and got to the question behind the question. Mark ends the story by recording that “they marveled at him” (v. 17).

As the American experiment continues to be tested in the years to come, those who love our country best will be those who are not Americans first. The sense of politics as ultimate leads us to do unspeakably awful things, harming our own country, because “desperate times call for desperate measures.” But Christians who are secure in our first priority—to seek the kingdom of God and to be citizens of that realm—can love our country well. We can render unto Caesar without veering into idolatrous worship of party, politicians, or democracy itself.

The New Testament honors the legitimacy of government—even really, really flawed governments like Rome. But that honor never includes making politics or government a source of identity or meaning in life.

We often can tell where our priorities are by what drives us to despair or to anger. I voted in this election, and if it goes a different way than I want, I’ll be worried and upset. But if I find myself in a frenzy or hopeless, I ought to rethink what it means to follow one who was tranquil before the government with the power to crucify him (John 18:33–36) while his disciples were fleeing, but then sweat drops of blood in prayer in the garden while those same disciples were asleep (Mark 14:37).

“Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” Other passages teach us about the separation of church and state, but that’s not what this text addresses. Other passages teach about the duty to pay taxes; that’s not the reason we have this one. This is about something we all should remember as we make our way to Election Day: that we are first and foremost Christians. That we belong to God.

We owe it to the legacy of George Washington and James Madison and Harriet Tubman and all the Americans who came before us to guard the institutions and freedom they handed on to us. We owe the same to the generations to come. Politics matter. But when politics start to define us, to control our sense of who we are, to keep us in a state of artificial exultation or artificial doom, we should recognize what’s happening.

Someone is handing us a coin. We should toss it back.

The Nightmare Before Christmas in a Secular Age

This week is the lead-up not just to Election Day but also to Halloween. Every year, sometime around this time, I will prompt groans from my youngest son, who’s 12, when I say, “Hey, let’s watch The Nightmare Before Christmas.” I like Tim Burton’s movie; my son hates it. I never, ever, until this week, though, ever thought about the film in terms of Charles Taylor’s magisterial A Secular Age.

Algorithms have broken us in almost every way, but, every once in a great while, they push something into one’s feed that actually provokes thought. This is one of those times. On X, a pastor by the name of Nicholas McDonald published a thread of 25 posts arguing that the film is actually about the forces Taylor describes.

McDonald points out that Jack, mayor of Halloweentown, is a skeleton of a man, experiencing the malaise of missing something (“the immanent frame”). All around Jack are representations of death (loss of meaning and purpose). Jack sets out to find meaning within that frame, McDonald says, and so represents “Naive Secularism.” The character Sally, on the other hand, stands in for “Realist Secularism.” McDonald writes: “So Sally, here, becomes a prophetic figure for what Jack ultimately must realize: the immanent frame can’t hold transcendent meaning.”

Entering into Christmastown, McDonald points out, Jack at first loves the meaning, beauty, and other goods of the place. “Rather than entering into the Christian Framework, Jack tries to borrow its values and drags them down into the immanent frame of Halloweentown,” McDonald writes. “Yet when he presents his Christened vision of human flourishing, the members of Halloweentown can’t fathom it.”

Jack tries to find Christmastown meaning, McDonald summarizes, through study and through romance, and then by making toys to cultivate the joy of Christmas: “But in order to accomplish this, he must also capture Santa Claus—our Christ figure—and LITERALLY BURY HIM UNDERGROUND.”

“Now Jack is free to ‘re-create’ Christmas within the immanent frame,” McDonald proposes. “But even in the name of love and goodwill (Christian language), he in fact spreads violence and terror.”

McDonald traces Jack’s Ecclesiastes-like realization that he and everything he values are ultimately dust, but this leads him to know that cannot be the center of this story.

“So … he returns to the grace to pursue the Christ figure he’s buried: Santa Claus,” McDonald writes. “Santa Claus now literally RISES FROM THE GRAVE, conquering the figure representing death/Satan: the Oogie Boogie Man.”

In the end, Jack cannot bring meaning to Halloweentown, McDonald shows. Santa Claus must dispense grace (snow) into it from the outside. Only then does Jack find love.

I long ago gave up on trying to find much, if any, insight or careful reflection on X/Twitter, but this was a worthy exception. Did Tim Burton mean the film to be an exploration of the disenchantment of the world in a secular age? Almost certainly not. But it is quite likely that he was, in fact, motivated by the loss of meaning in the current age. And, while Carl Jung was wrong about many, many (don’t get me started), many things, he was right that our stories aren’t just made up out of nothing. They are rooted in our own life experience, but also—more importantly—in the experience of humanity as a whole.

Anyway, I loved the thought exercise. I can predict I won’t watch Nightmare Before Christmas the same way again, and next year when my son groans at the suggestion, I’ll say, “Let’s watch it as a metaphor on the aridity of secularism and the wonder of the Incarnation.” He will sigh even louder—he’ll be 13 by then—but that will be my way of throwing some snow into the air.

A C. S. Lewis Poem That Wrecked Me This Week

A couple weeks ago, the poet Malcolm Guite came into town here in Nashville and a few of us gathered with him for a fun evening, at which he read to us from the amazing project he’s working on right now. After he was out at Biola University later, my friend Matthew Hall wrote in his newsletter about Guite explaining and walking through C. S. Lewis’s poem “As the Ruin Falls.”

I am sure I’ve read this poem before; I’ve been reading all of Lewis since I was 14 or 15 years old. But I didn’t remember this one. It’s to his wife Joy Davidman, on the prospect of her death. Here it is.

“As the Ruin Falls”

By C. S. Lewis

All this is flashy rhetoric about loving you.

I never had a selfless thought since I was born.

I am mercenary and self-seeking through and through:

I want God, you, all friends, merely to serve my turn.

Peace, re-assurance, pleasure, are the goals I seek,

I cannot crawl one inch outside my proper skin:

I talk of love—a scholar’s parrot may talk Greek—

But, self-imprisoned, always end where I begin.

Only that now you have taught me (but how late) my lack.

I see the chasm. And everything you are was making

My heart into a bridge by which I might get back

From exile, and grow man. And now the bridge is breaking.

For this I bless you as the ruin falls. The pains

You give me are more precious than all other gains.

No Newsletter Next Week

I’m not planning on sending out this little message in a bottle next week. The presidential election, after all, will be on Tuesday, and that will be almost all that’s on anyone’s minds. There’s no way I can know the outcome in time to get this ready to send out. I’ll be back the week after (I pray we know the result by then).

Desert island bookshelf

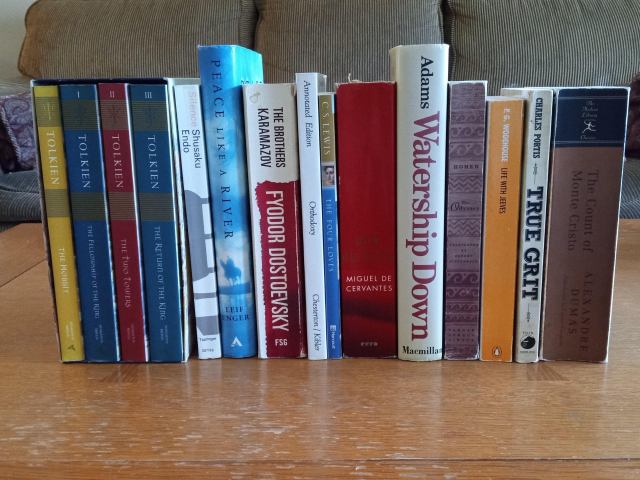

Every other week, I share a list of books that one of you says you’d want to have on hand if you were stranded on a deserted island. This week’s submission comes from reader Jonathan Schindler from Lombard, Illinois, who writes: “Thanks so much for your newsletter—it’s a weekly dose of sanity in my inbox, and I’m grateful for it. I’ve thought about sending a desert island book list in for a long time, but there are so many good choices that I get locked up. Today I decided to no longer let the perfect be the enemy of the good, so here’s my desert island bookshelf.”

- The Lord of the Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien

- Silence by Shusaku Endo: Most of my favorite books are big tomes, but Endo manages in just 200 or so pages to get at what it means to follow Jesus in unthinkable circumstances. Each time I reread it, I find I identify with a different character in the story.

- Peace Like a River by Leif Enger: A beautiful book that I’m in the mood for every winter.

- The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky: On a desert island, I’ll finally have time to sit and give this book the attention it deserves.

- Orthodoxy by G. K. Chesterton: This is a book I reread each year. If only every book about Christian faith were written with such joy and wit!

- The Four Loves by C. S. Lewis: I’ve always loved Lewis’s nonfiction, and this is probably my favorite of the bunch.

- Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes

- Watership Down by Richard Adams: This is the only book on this shelf I’ve read just once, and for the first time last year, but it was so beautiful and so moving, I wanted to start over immediately after I finished.

- The Odyssey by Homer

- Life with Jeeves by P. G. Wodehouse: I realized I wouldn’t want to be stuck anywhere without a P. G. Wodehouse omnibus.

- True Grit by Charles Portis: Portis is a master of voice, and True Grit is something special in this regard. A hilarious narrator carries you through a great tale that explores the cost of judgment and revenge.

- The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

Thank you, Jonathan!

Readers, what do y’all think? If you were stranded on a desert island for the rest of your life and could have only one playlist or one bookshelf with you, what songs or books would you choose?

- For a Desert Island Playlist, send me a list between 5 and 12 songs, excluding hymns and worship songs. (We’ll cover those later.)

- For a Desert Island Bookshelf, send me a list of up to 12 books, along with a photo of all the books together.

Send your list (or both lists) to questions@russellmoore.com, and include as much or as little explanation of your choices as you would like, along with the city and state from which you’re writing.

Quote of the Moment

“I am anxious to make it clear that I was not a rebel, except by force of circumstances.”

—George Orwell

Currently Reading (or Re-Reading)

- Norman Wirzba, Love’s Braided Dance: Hope in a Time of Crisis (Yale University)

- Bob Woodward, War (Simon & Schuster)

- Brad East, Letters to a Future Saint: Foundations of Faith for the Spiritually Hungry (Eerdmans)

- W. B. Yeats, The Poems (Everyman’s Library)

Join Us at Christianity Today

Founded by Billy Graham, Christianity Today is on a mission to lift up the sages and storytellers of the global church for the sake of the gospel of Jesus Christ. For a limited time, you can subscribe and get two years for the price of one. You’ll get exclusive print and digital content, along with seasonal devotionals, special issues, and access to the full archives. Plus, you’ll be supporting this weekly conversation we have together. Or, you could give a membership to a friend, a pastor, a church member, someone you mentor, or a curious non-Christian neighbor. You can also make a tax-deductible gift that expands CT’s important voice and influence in the world.

Ask a Question or Say Hello

The Russell Moore Show podcast includes a section where we grapple with the questions you might have about life, the gospel, relationships, work, the church, spirituality, the future, a moral dilemma you’re facing, or whatever. You can send your questions to questions@russellmoore.com. I’ll never use your name—unless you tell me to—and will come up with a groan-inducing pun of a pseudonym for you.

And, of course, I would love to hear from you about anything. Send me an email at questions@russellmoore.com if you have any questions or comments about this newsletter, if there are other things you would like to see discussed here, or if you would just like to say hello.

If you have a friend who might like this, please forward it, and if you’ve gotten this from a friend, please subscribe!

Russell Moore

Editor in Chief, Christianity Today

P.S. You can support the continued work of Christianity Today and the Public Theology Project by subscribing to CT magazine.

Moore to the Point

Join Russell Moore in thinking through the important questions of the day, along with book and music recommendations he has found formative.

Delivered free via email to subscribers weekly. Sign up for this newsletter.

You are currently subscribed as no email found. Sign up to more newsletters like this. Manage your email preferences or unsubscribe.

Christianity Today is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

“Christianity Today” and “CT” are the registered trademarks of Christianity Today International.

Copyright ©2024 Christianity Today, PO Box 788, Wheaton, IL 60187-0788

All rights reserved.