Less than a year before the US presidential election, pastors took to their pulpits to decry a culture of hate, extremism, and vile politics.

“Much of the hate and discord that has been poisoning our nation has been preached in the name of Christ and the church,” Charles V. Denman declared.

In a different sanctuary, William Dickinson proclaimed, “Hate knows no political loyalty and is as deadly and as vicious in the heart and mind of liberals and those to the far right as to the far left alike.”

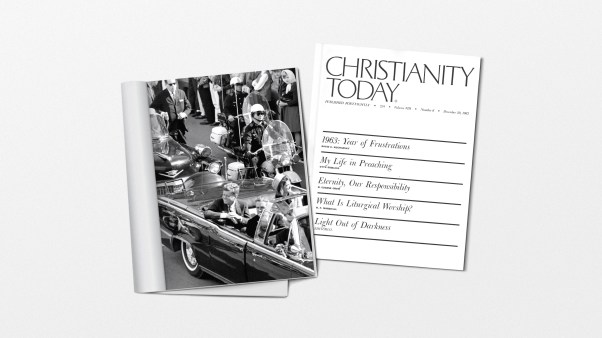

Those sermons were delivered not during the current race for the White House—but in the aftermath of the November 22, 1963, assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

To mark the 60th anniversary of Kennedy’s death, a leading scholar on faith and politics sees lessons in the decades-old messages for Americans today.

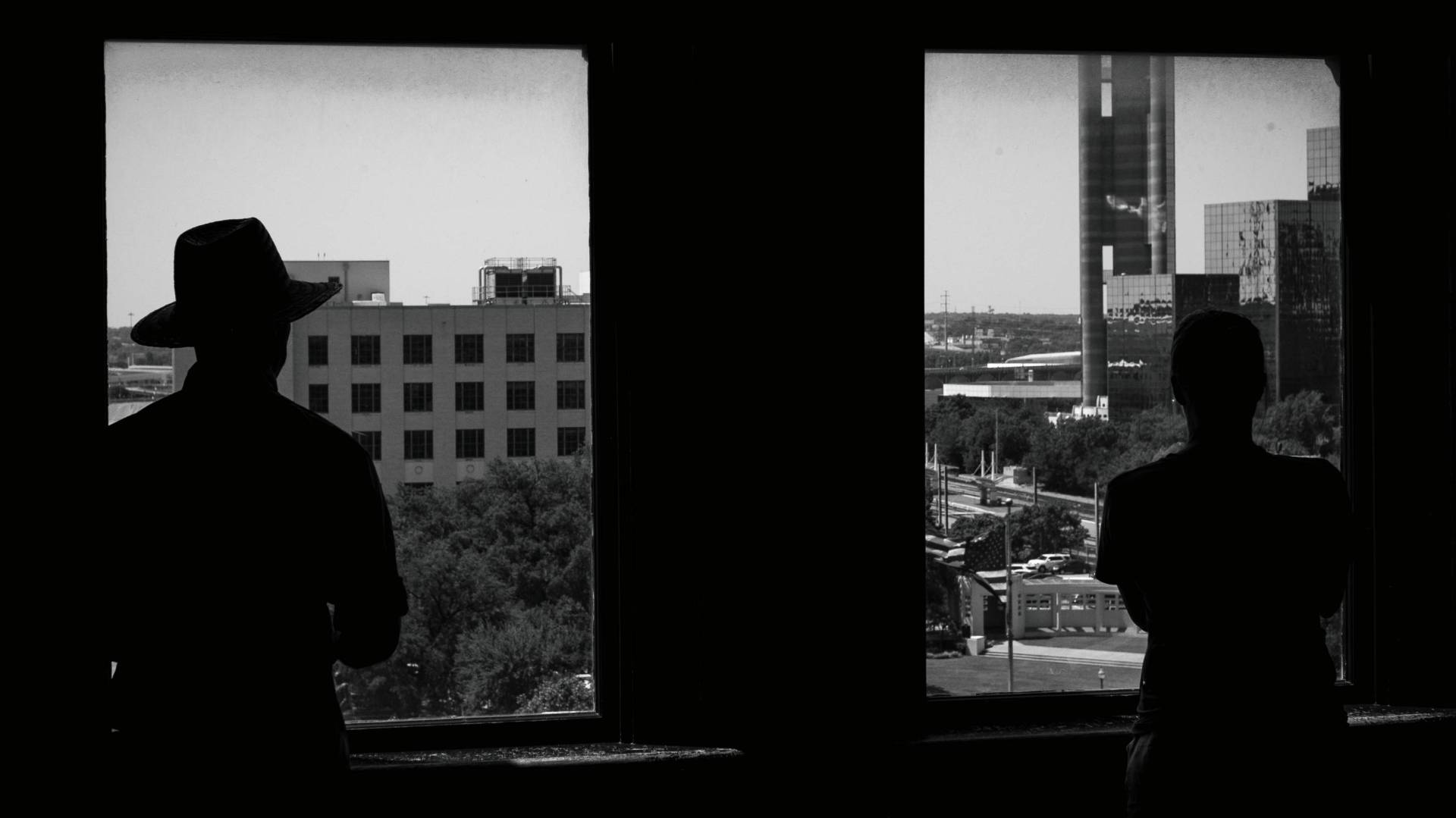

“One overarching theme emerges again and again: a call for civility, a call for condemnation of extremism and a call to end the divisions and polarizations … that they think provided the climate in which this assassination could occur,” said Matthew Wilson, director of Southern Methodist University’s Center for Faith and Learning. “That is really striking because so much of what they say seems to apply to our current moment.”

Library archives at SMU’s Perkins School of Theology include sermons preached to overflowing crowds on November 24, 1963—the Sunday after the shooting.

The transcripts, mostly from Methodist churches, are in the papers of the late William C. Martin, a Methodist bishop and president of the National Council of Churches.

“He reached out to Dallas clergy … asking for copies of the sermons preached after the assassination,” SMU spokeswoman Nancy George said.

In a few cases, the pastors finished their remarks only to be handed notes informing them of alleged assassin Lee Harvey Oswald’s shooting death. Nightclub owner Jack Ruby gunned down Oswald during his transfer from one jail to another that Sunday morning.

At the time of Kennedy’s killing, Dallas had a reputation as an ultraconservative city that didn’t treat liberals kindly. The day before the assassination, handbills distributed in Dallas featured convict-style photographs of Kennedy and the caption “Wanted for Treason.”

The next day, a full-page ad appeared in the Dallas Morning News:The “American Fact-Finding Committee” demanded to know why the president had “ordered the Attorney General to go soft on communism.”

So when Kennedy—a liberal Democrat and the first Catholic elected to the nation’s highest office—was killed, the backlash against Dallas was immediate.

“One of the interesting ironies here is that the tendency to blame Dallas, or to criticize Dallas politics in the 1960s, was to focus on right-wing extremism and groups like the John Birch Society and some of the very strident anti-communists who had been very critical of John Kennedy,” Wilson said.

“But it turned out that those weren’t the people who killed Kennedy,” the political science professor added. “It turned out to be a left-wing extremist, a Marxist sympathizer in Lee Harvey Oswald, who killed Kennedy, and some of the pastors wrestle with that.”

Oswald’s role “served as a reminder that this blind ideological hatred is not confined to one corner of the political universe,” Wilson said. “It occurs in the service of multiple causes, multiple ideologies. And I think that’s instructive for our day as well. That is, we see a lot of contempt for and dehumanization of political adversaries coming from across the spectrum.”

For city leaders in 1963, the first priority was to “create distance between Dallas collectively or corporately and this horrible event,” Wilson noted.

But pastors who shared their sermons with Martin called for self-examination and change, the transcripts reveal.

At Northaven Methodist Church, William A. Holmes asked, “In the name of God, what kind of city have we become?”

He titled his message “One Thing Worse Than This.”

Worse than Kennedy’s death, Holmes preached, would be the citizens of Dallas refusing to take any responsibility.

“Yet that already seems to be the slogan of our city and some of its officials: ‘Dallas is a friendly city—this was the work of one madman and extremist.’ ‘Our hearts are saddened—but our hands are clean.’ How neat and simple this solution,” Holmes said. “How desperately that we wish it were true.”

Holmes stressed that he was aware of the left-wing nature of Oswald’s ideologies.

“But my friends,” the pastor added, “whether extremism wears the hat of left wing or right wing, its by-products are the same. It announces death and condemnation to all who hold a different point of view.

“And here is the hardest thing to say: There is no city in the United States which in recent months and years has been more acquiescent toward its extremists than Dallas, Texas. We, the majority of citizens, have gone quietly about our work and leisure, forfeiting the city’s image to the hate-mongers and reactionaries in our midst. The spirit of assassination has been with us for some time. Not manifest in bullets but in spitting mouths and political invectives.”

CBS broadcast a portion of Holmes’ sermon, prompting death threats and New York Times coverage of police guarding him, as the United Methodist News Service recounted in 2013.

At Highland Park Methodist Church, pastor Dickinson told congregants they’d be shocked by what a respectable Christian couple of fine education said at a dinner party two nights before the president’s visit.

The couple, he said, “told friends they hated the president of the United States and that they wouldn’t care one bit if somebody did take a potshot at him.”

“There are among us today,” Dickinson preached, “too many purveyors of hate, people who call intelligent, sincere holders of public office traitors. People who fill our cars with leaflets bearing printed lies and calling our public officials disloyal. People who fill our mail with emotional, bitter harangues and accusations and who make harassing telephone calls to our honest and sincere citizens at all hours of the night. And then there are those who give subtler approval to such extremists and breeders of hate through either indifference or through financial support.

“Hate not only in our city but throughout our nation has become big business and is supported by large contributions and exceedingly competent leadership,” he added. “But we in Dallas, it seems to me, have more than our share of these extremists. It is not a pretty picture into which stepped an assassin.”

At Wesley Methodist Church, pastor Denman recounted that he and his two boys witnessed the president’s motorcade up close (“so closely we could have almost reached out and touched it”) before later hearing sirens and learning of the shooting.

“Did he have to die to get Christians to quit hating?” Denman said he asked his weeping wife after arriving home.

“In Dallas, entire sermons have been devoted to damning the Kennedy administration and the United Nations, and they have been delivered from Methodist pulpits,” he told the congregation. “In the name of the church, men and women have sown seeds of discord, distrust and hate and have called it witnessing for Christ.

“As a church, we are sick,” he continued. “God have mercy on us.”

Less than a week after Kennedy’s assassination, Jimmy Allen, secretary of the Baptist General Convention of Texas’ Christian Life Commission, spoke at a community Thanksgiving service.

Allen agreed with those concerned about Dallas’s image that “it could have happened anywhere … in any city.”

However, he stressed, “Something far deeper and more disconcerting is the fact that so many in our nation were not surprised that it happened here!”

“A climate of character assassination, carping criticism toward national leaders and constant complaint about the processes of law has developed in our nation,” Allen said. “Dallas is not the only city where this has been present. But it has been present.

“Disrespect for persons and democratic processes,” he added, “has grown to alarming proportions in our community and encourages the venting of hatred both by young and old.”

In a January 1964 radio address included in the SMU papers, Rabbi Levi A. Olan of Temple Emanu-El addressed the question of Dallas’s “guilt” in Kennedy’s death.

“In the beginning … many people felt that there was something frightfully wrong with the city, and some wanted to face the truth,” Olan said. “This mood is passing, and now there is a growing resentment of all criticism from without and within the gates.

“The present tone is that of rejecting all responsibility and disclaiming all guilt,” he suggested. “Dallas, it is said, is no different than other cities and better than many. The assassin was not one of our citizens. The people want desperately to forget the tragedy and go on with the business of living as though nothing had happened here.”

Six decades later, Wilson—the SMU political scientist—points to striking similarities between then and now.

“We talk a lot about the polarization, the ideological extremism, the hatred, the rhetoric of violence in our contemporary politics,” he said. “And it is instructive to see that that is not a new phenomenon, that there was a lot of concern about those very things in what a lot of us kind of think of as the good old days of American politics.”

Bobby Ross Jr. is a columnist for

and editor in chief ofThe Christian Chronicle

. In 2003 he produced an in-depth package for AP on the 40th anniversary of the JFK assassination. This article first appeared on .