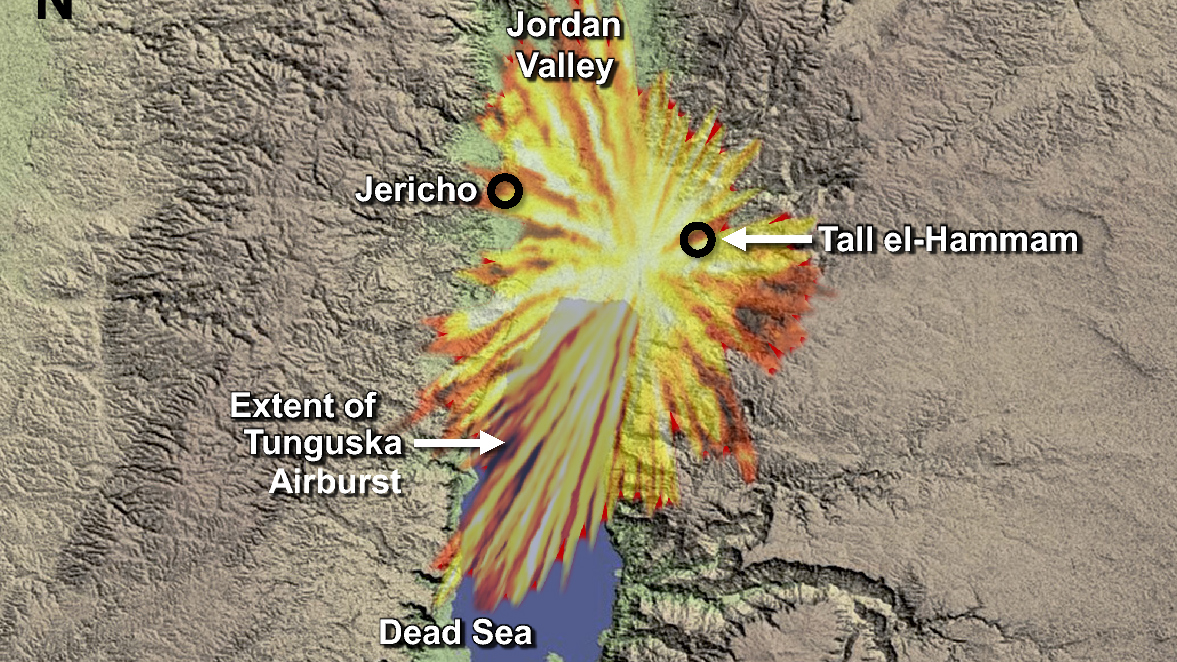

A fireball exploded over the northern shore of the Dead Sea around 1650 BC, according to the findings of a multidiscipline team of 21 scientists. The explosion laid waste to the entire lower Jordan River Valley, sowing Dead Sea saltiness that ruined agriculture for several hundred years.

The huge 100-acre city located at what is today called Tall el-Hammam east of the Jordan River was destroyed, along with a dozen other smaller cities and multiple small villages. They were abandoned and uninhabited for hundreds of years.

The highly technical report—published this week in Scientific Reports, an online peer-reviewed journal, and already accessed more than 100,000 times—noted in conclusion the similarity to the biblical account of the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah: “There are no known ancient writings or books of the Bible, other than Genesis, that describe what could be construed as the destruction of a city by an airburst/impact event.”

However, amid the wave of headlines, the unofficial peer reviews on social media from a number of archaeologists with varying degrees of familiarity with the Tall el-Hammam excavation were highly skeptical. As Christianity Today reported seven years ago, few archaeologists outside of those working on the excavation team believe that Tall el-Hammam is Sodom.

“In my opinion, this is an example of evidence being marshaled to support the identification of the site as Sodom, as opposed to letting the site speak for itself and then—if the evidence supports it—put forth a proposal of it as Sodom," archaeologist Robert Mullins told CT. Chair of the Department of Biblical Studies at Azusa Pacific University, he currently codirects the excavation at Abel Beth Maacah, a site in northern Israel. He is also listed on the Tall el-Hammam excavation website as a ceramic consultant.

Mullins, along with other evangelical archaeologists and Bible scholars, cite chronology as a major issue with the Sodom identification. The Bible’s internal chronology places Abraham and the events in his life, including the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, three to four centuries earlier. At 1650 BC, the Israelites were in Egypt, with the Exodus still 200 years in the future.

Pottery is a key tool for archaeological dating. Mullins, reviewing Tall el-Hammam pottery, saw a lot of 16th-century BC pieces, which seems to indicate the city was destroyed after the date of the airburst fireball described in the article.

Archaeologists Steve Ortiz, director of Lipscomb University’s Lanier Center of Archaeology, agreed that while Tall el-Hammam is an important site, its destruction date is too late to fit the Sodom scenario. He dismissed the fireball hoopla to CT. “[Their] destruction does not look any different than any other destruction,” he said. “We have Assyrian and Egyptian destructions at Gezer that looks just as dramatic.”

Israeli archaeologist Aren Maeir of Bar Ilan University noted a lack of citations to other studies of the archaeology of destruction and thought the destruction the report described was not that unusual. “I see some things that remind me of phenomena that we have in the Iron Age IIA (1000–925 BC) destruction at Tell es-Safi/Gath (e.g. vitrified or “melted” bricks, ultra-high temperatures, and other things)—a destruction that is most likely caused by the conquest and destruction of the site by Hazael of Aram,” he said. Hazael’s attack on Gath is reported in 2 Kings 12:17.

The archaeological disagreement over Sodom centers not only on the chronology but also on the location. Sodom is conventionally located more to the south end of the Dead Sea.

Steven Collins, the codirector of the Tall el-Hammam excavation, often quotes Genesis 13, where Abraham and Lot camped between Bethel and Ai and looked down on Sodom, which seems to favor its location north of the Dead Sea. But Mullins said Collins dismisses Genesis 18:16. “Abraham is at Mamre looking down at Sodom; one cannot see Hammam from the Hebron area,” he observed.

Whether it’s a fireball that destroys a city, a mighty wind that holds back the waves of the Red Sea, an ark that landed on a mountain after a global flood, or celestial events that herald a royal baby’s birth, there’s a tendency to look for naturalistic explanations for biblical miracles—as if that would prove the Bible to skeptics.

The scientists who wrote this report on the Jordan River Valley fireball state, “An eyewitness description of this 3600-year-old catastrophic event may have been passed down as an oral tradition that eventually became the written biblical account about the destruction of Sodom.”

If the Bible is just a collection of oral traditions that were puzzled together centuries later, perhaps the fireball would fit. But a century and a half of increasingly detailed archaeological investigation shows time and again that the historical framework of the biblical story holds up back to the time of Abraham.

“There is no question that this is an amazing site,” Mullins concluded. All of the archaeologists would agree with that. “But they are going to have to put forth more evidence that it’s Sodom.”

Gordon Govier is host of The Book and The Spade podcast and editor of ARTIFAX magazine.