Caught in a decades-long battle over LGBT issues, with a proposed denominational split delayed again by the pandemic, dozens of conservative and progressive churches are leaving the United Methodist Church (UMC) without a tidy exit plan.

Two years ago, factions in the United Methodist Church (UMC) agreed on a plan for splitting the denomination with conservative churches keeping their property as they leave. But the UMC has twice postponed its General Conference and won ’t meet until August 2022 to vote on the proposal, called the “Protocol of Reconciliation and Grace Through Separation.”

A United Methodist News review of US annual conference reports and publicly available journals found that the 54 conferences—regional UMC governing bodies—approved at least 51 disaffiliations in 2020. Annual conference reports for 2021 show that the annual conferences have approved 38 disaffiliations so far in 2021.

Though the disaffiliations represent a sliver of the more than 31,000 United Methodist churches nationwide, they show that some churches are willing to take the hard way out of the UMC.

“For us, we felt the Lord was leading us to go. As far as the protocol is concerned, it ’s something that is up in the air,” said Alvin Talkington, a member of the disaffiliation team at Boyce Church, a 100-member congregation in Ohio that left the denomination last fall.

The decision to leave came after years of frustration with the East Ohio Conference for not valuing the church’s conservative doctrinal stance on issues such as homosexuality and not finding conservative ministers to serve the church.

“Out of the last ten pastors, there might have been three or four who fit our doctrine,” said Talkington. The church hired its most recent pastor without the help of the annual conference, and the lay leadership led the effort to disaffiliate.

The move came at a cost to the East Liverpool, Ohio, church.

For centuries the denomination has maintained a trust clause, which states that churches hold property in trust for the entire denomination. To depart with property, churches can use a provision added by the 2019 special session of the General Conference, allowing churches to disaffiliate for “reasons of conscience” related to human sexuality. This addendum is sometimes called Section 2553.

Even under Section 2553 disaffiliation requires churches to pay hefty financial obligations to their conferences: several years of contributions to the pension and payment of two years of aportionments, money local churches give to support the conference and denomination. Though not specified in Section 2553, some conferences also require churches to pay a percentage of the church’s total assets. The annual conferences must also vote to release a church. But if churches waited until the protocol ’s approval, they could walk away with their buildings and no major fees.

Leaders at Boyce firmly believed its future was not with the UMC and weren ’t sure when the protocol would be approved or what the final language would be, so the church disaffiliated under Section 2553 last September. It had to pay a $92,000 fee on the way out.

“The protocol provides a way for churches to leave and for pastors to keep their pensions without fees,” said John Lomperis, United Methodist director for the Institute on Religion and Democracy. “If you go through the protocol, the denomination waives its right to assert the trust clause and churches can keep buildings.”

Another church that opted to leave before the protocol vote was the United Church of Altona, now The Grove Community Church of Altona, Illinois.

The church cited concerns over leadership as its reason for disaffiliating and paid over $120,000 to leave the Illinois Great Rivers Conference. The congregation felt like the conference did not support the church as it struggled to find and maintain good pastoral leadership.

“We were floundering, and we were afraid if we kept going the way we were, we would keep losing members,” said Carla Gibbons, a member of the Grove Community Church disaffiliation team.

Before 2020, the majority of disaffiliating churches have been on the traditional side of the theological spectrum. Most have left citing weariness with the debate or a lack of enforcement of the denomination ’s bans related to homosexuality.

Some of these churches, like Grace Fellowship Church in Katy, Texas, have found a new home in the conservative Free Methodist Church, while others, like Boyce Church and Grove Community Church, are moving forward as independent churches.

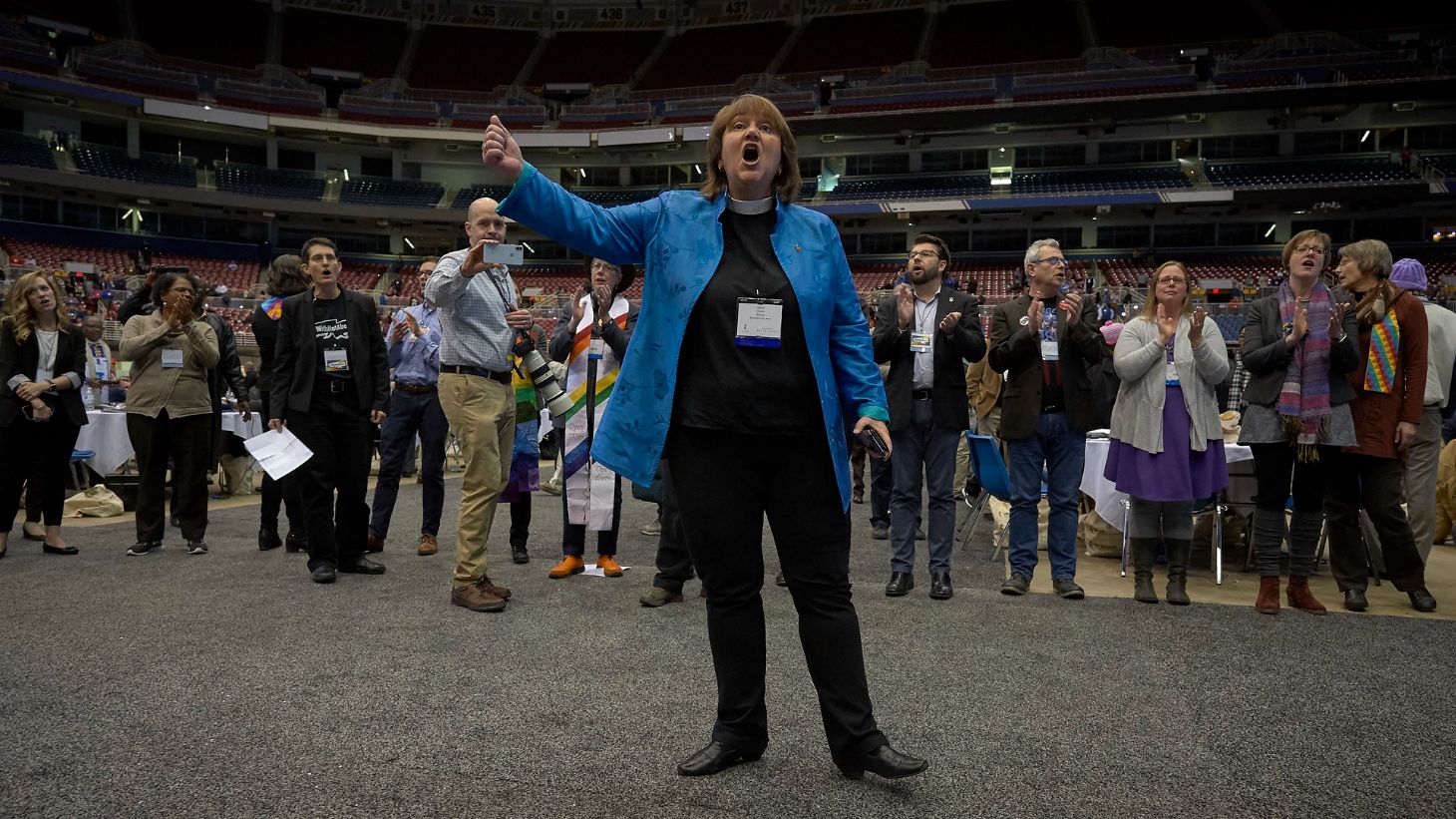

But progressive churches are leaving the UMC, too. In 2020, three Maine churches and one Texas megachurch left the UMC over what they see as LGBT discrimination. Houston ’s Bering Memorial United Methodist Church left the UMC for the United Church of Christ. New Brackett Church in Peaks Island, Maine, became independent, but the church and its pastor are considering joining both the United Church of Christ and the Unitarian Universalist Association.

“We feel that this decision would allow maximum participation from a wide spectrum of people and beliefs in the life of our church,” the church website says.

Progressive churches leaving the denomination also consider the Alliance of Baptists and the UK-based Inclusive Church. In June, leaders of Love Prevails, a group of UMC progressive pastors, announced their departure from the denomination.

The Wesleyan Covenant Association, which includes 125,000 people in 1,500 churches, formed to lobby in favor the UMC’s traditional marriage stance. Now, the group has become the core of the Global Methodist Church, a conservative denomination to receive departing congregations after the split.

Neither the UMC nor the Global Methodist Church want churches striking out on their own.

Will Willimon, professor at Duke Divinity School, sees how students studying ministry are worried about what the denomination will look like when they are ready to enter it. “I think bishops should be pleading with people to please stay,” he said.

He wonders if the exodus of churches will force remaining churches and UMC leaders to put the focus back where it needs to be: on local churches ministering in their communities.

“I advise people to stay focused on the local mission. This is the basic unit of the church, and maybe if we can recover that, we could be okay,” Willimon said.

Lomperis hopes that some of the conservative churches that have left the UMC will eventually join the Global Methodist Church. He understands the frustration churches feel toward conferences that don ’t value their conservative theology. But rejecting the denominational structure isn ’t the answer, he said. He hopes that the Global Methodist Church can develop a leaner, less bureaucratic arrangement that gives more power to local congregations.

“We strongly discourage any premature quitting and encourage people to wait on the protocol. For those who have left, we hope that later when we get the protocol, they will come join the GMC,” he said.

Since leaving the UMC, members of The Grove Community Church have hired a part-time, independent pastor to lead the congregation. Gibbons is encouraged to see attendance up from 20 to 90 in worship, a combination of new families and returning members, even as she acknowledges there is always a honeymoon period with a new pastor.

And members of former UMC churches maintain their appreciation for historic Methodism and its contributions to global Christianity.

“The United Methodist Church has probably done more globally than just about any other denomination there is,” said Talkington of Boyce Church. “They do a lot of good, but this scriptural thing—they are just willing to tear it apart.”