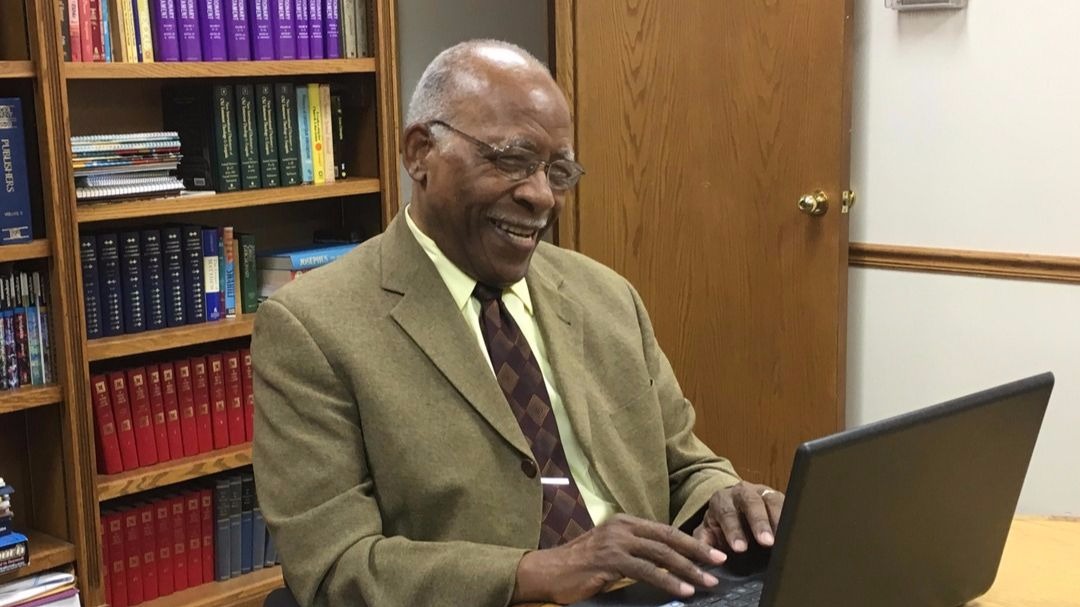

Melvin E. Banks, founder of the largest black Christian publishing house in the United States, died on February 13 at age 86.

Banks started Urban Ministries Inc. in the basement of his home in Chicago in 1970, focusing on Sunday school curriculum and Bible study materials for African American Christians. The ministry grew to serve more than 50,000 black churches.

Banks contextualized Scripture to show its relevance to contemporary African American life and shocked many Christians, black and white, with depictions of Bible characters as people of color. Banks insisted the images were accurate, since the world of the biblical narrative included Middle Easterners as well as many North Africans, and also argued it was important. Black people needed to know they were part of Bible history.

“When I grew up, all the Sunday school literature was produced by white people and all the writing was done from a white perspective,” he said. “All the biblical characters were portrayed as white people. It dawned on me that the material as published did not connect.”

White evangelicals sometimes accused Banks of being a black separatist or even supporting segregation and racism by focusing his ministry on black Christians and black churches. Banks, a graduate of Moody Bible Institute and Wheaton College, rejected the idea, saying it was just clear that black Christians couldn’t count on white Christians to help them understand the Bible.

“The bottom line is Jesus,” he said, “and his supremacy.”

Moved to make his own commitment to Christ

Banks was born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1934. He was largely raised by his sister, who was two years older than him, while his mother worked for a white family from Monday to Friday.

When Banks was 9, a black church planter from a Brethren Assembly in Detroit told him how to accept Jesus with a lesson about the Apostle Paul’s answer to the Phillippian jailer in Acts 16. Banks was moved to make his own commitment to Christ.

“The next week, on my own, I thought about what he said and I prayed, ‘Lord Jesus, come into my life and save me,’” Banks recalled during an oral history interview in 2004.

When Banks turned 12, the church planter started taking him to tell his testimony around Birmingham. Once, when Banks finished explaining “how to really get into the family of God … by believing in Jesus Christ, and not just running to church,” an elderly man gave him an encouraging word and a Bible quote.

“He had gray hair, and he was just sort of—hands behind his back,” Banks recalled. “He said, ‘You know, Hosea said it a long time ago, “My people are destroyed for lack of knowledge.”’ I had never heard of that verse before, but when he quoted it, it suddenly became a very important verse for me.”

Banks went to Moody in 1952 to study the Bible. Coming in from the South by train, he was first overwhelmed by the city’s large buildings, and gawked up at the men and women leaning out of the windows in the late summer heat. But the greater shock came at Moody, where Banks was one of about 10 black people at a school with 1,000 students. Some of his fellow students had never seen a black person and gawked at him as he went to and from classes. He wasn’t assigned a roommate, which he only later realized was because the school wouldn’t house a white student with a black student.

“While they were accepting a few black people, they really were not accepting them in the fullest sense of the word,” Banks said. “They were permitted to come and stay there.”

He didn’t need to escape his blackness

Banks didn’t leave campus to find a black church until a Bahamian chapel speaker from the Brethren Assemblies pulled him aside and said, “Melvin, you need to be finding some people, some of your kinfolks.” The visitor sent the young man to a Brethren church on the South Side of Chicago.

It was a critical moment for Banks. He realized he didn’t need to escape his blackness, and that acceptance by white people was not enough for him. He needed to understand his identity as a person and a Christian independent of what white people thought.

Banks met his wife, Olive Perkins, at the Brethren church. They married in 1956, one month after Banks turned 21. They helped plant a new church, Westlawn Gospel Chapel and Banks commuted from the city to Wheaton to study biblical archaeology.

When he graduated from Wheaton with an M.A. in 1960, he took a job at Scripture Press Publishers. He was hired to sell the company’s Sunday school material to black churches, but soon began to push the publisher to make changes to its curriculum.

“They had a desire to get literature—good stuff—into black churches, but they didn't know how to do it. So, I went out with the idea that I was going to do that, but then I ran into difficulty trying to persuade black churches to take literature that was white,” Banks explained.

At the same time, Banks was starting to think differently about race. He was provoked by the Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammed, who said black people didn’t know their own history because it was stolen from them like their fathers and mothers had been stolen from Africa. While the black nationalist was “just talking off the wall,” according to Banks, he also had a point. Banks realized that, apart from the time someone gave him a copy of Booker T. Washington’s Up From Slavery, he’d never been taught black history.

Banks then discovered The Black Man in the Old Testament and Its World, by Alfred G. Dunston Jr., a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. He realized he’d never been taught the black history of the Bible. In fact, though most of the biblical stories are located in the Middle East and the people in the stories are from the Middle East, North Africa, and the Mediterranean, he personally imagined every character in the Bible as a Northern European.

Banks pitched the idea of Sunday school curriculum depicting black people to his bosses at Scripture Press Publishers, but they weren’t interested. Then he got a new white colleague who worked in marketing to pitch the idea, using the terminology of “niche marketing.” The plan was approved.

Banks, however, decided he needed to do it himself. He left Scripture Press Publishers with a blessing and a little financial backing, and started his own business.

“I decided that if this company is going to really go, it can’t be a part of a white company,” Banks recalled. “It needed to be independent, so that we could make our own decisions and do what we think is necessary to make it go.”

‘I thought you would stick with it’

The company almost didn’t survive the first few years. Banks struggled financially, running the business in the red. He thought about quitting all the time. In fact, there were more than 40 black-owned publishers launched in the US around 1970, and all but four or five of them went out of business within a few years. Banks, however, kept getting divine assurance that he should continue.

“Why did you ask me to take on this job?” he once asked God. “You know I am not a great business person.”

Then he felt the presence of the Holy Spirit like a physical vibration. He felt God say, “Melvin, I did not ask you to do this because I thought you were so smart …. I asked you because I thought you would stick with it.”

So Banks stuck with it.

Still, for a number of years he assumed he would be forced to close when he couldn’t pay the printer’s bills. But the white-owned company in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Dickinson Press, kept filling his new orders, even though he was delinquent on his past payments. When Banks later asked why, the Christian owners told him they could afford to support his new ministry, so they did.

Urban Ministries Inc. broke even for the first time in 1976 and then continued to grow and flourish. Banks identified 70 to 80 black-owned bookstores around the country to sell his publications, along with 400 to 500 white-owned Christian bookstores that served black churches. He established direct connections with churches around the country, and supplied them with new educational material every quarter for more than four decades.

Wheaton recognized Banks with an honorary doctorate in 1992; Moody named him Alumnus of the Year in 2008; and he received a lifetime achievement award from the Evangelical Christian Publishers Association in 2017.

Banks said that when he died, though, he just wanted to be remembered as someone who was faithful.

“If it could be said,” he told a historian in 2004, “that here was a man who had a dream of seeking to communicate the truth of God's Word to people, and he was able to make some contribution along that line, then I think I would be pleased.”

Banks is survived by his wife Olive and his three children Melvin Jr., Patrice Lee, and Reginald. Details about funeral arrangements will be announced soon.