In tonight’s debate, the first between President Donald Trump and Joe Biden, the two candidates will have a lot of ground to cover. They’ll be addressing top issues for voters like the response to COVID-19, the economy, health care, and the makeup of the Supreme Court.

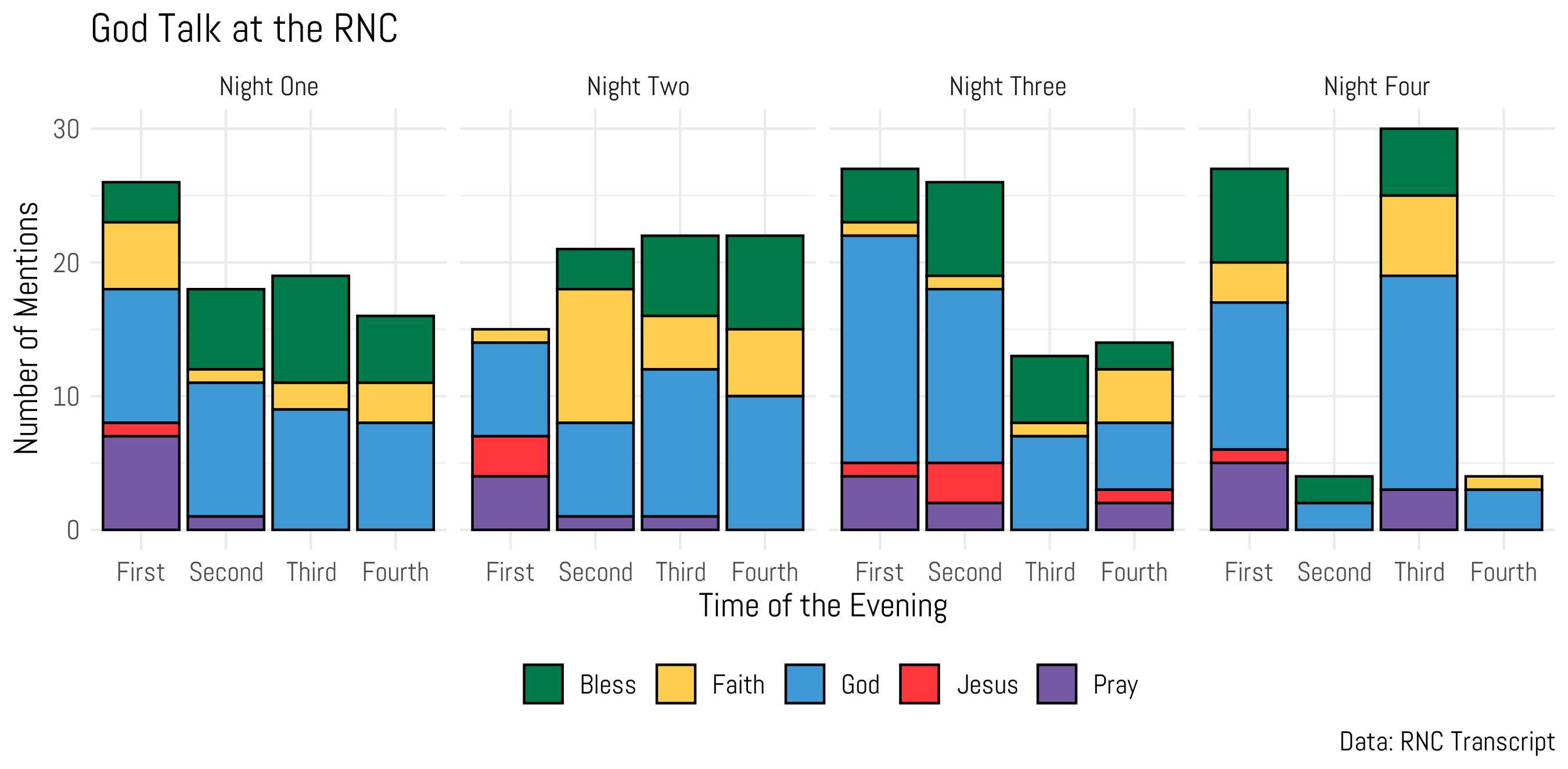

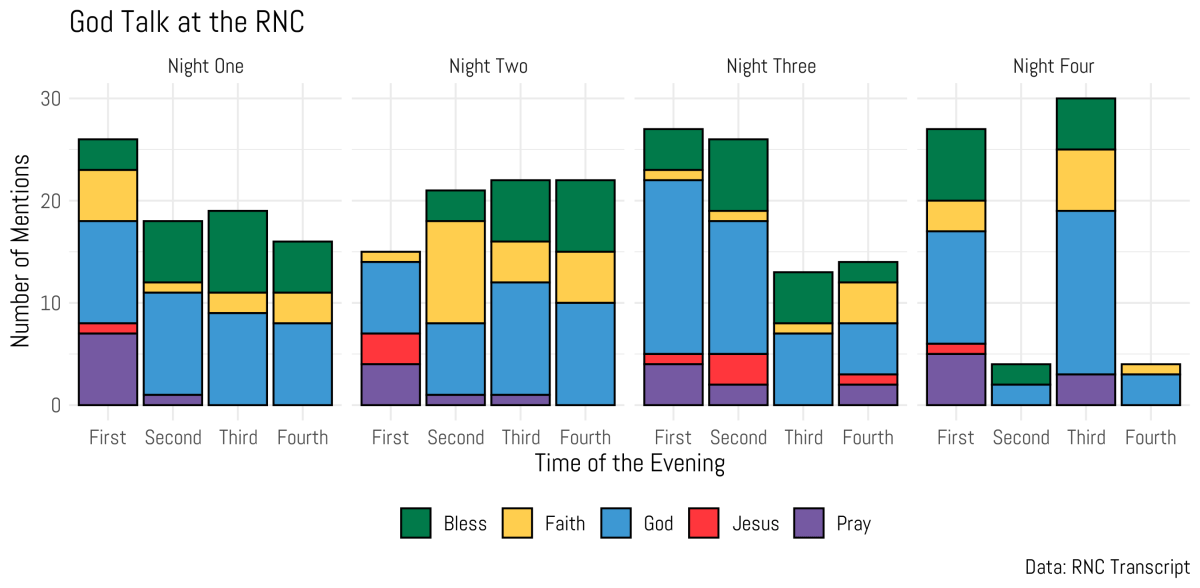

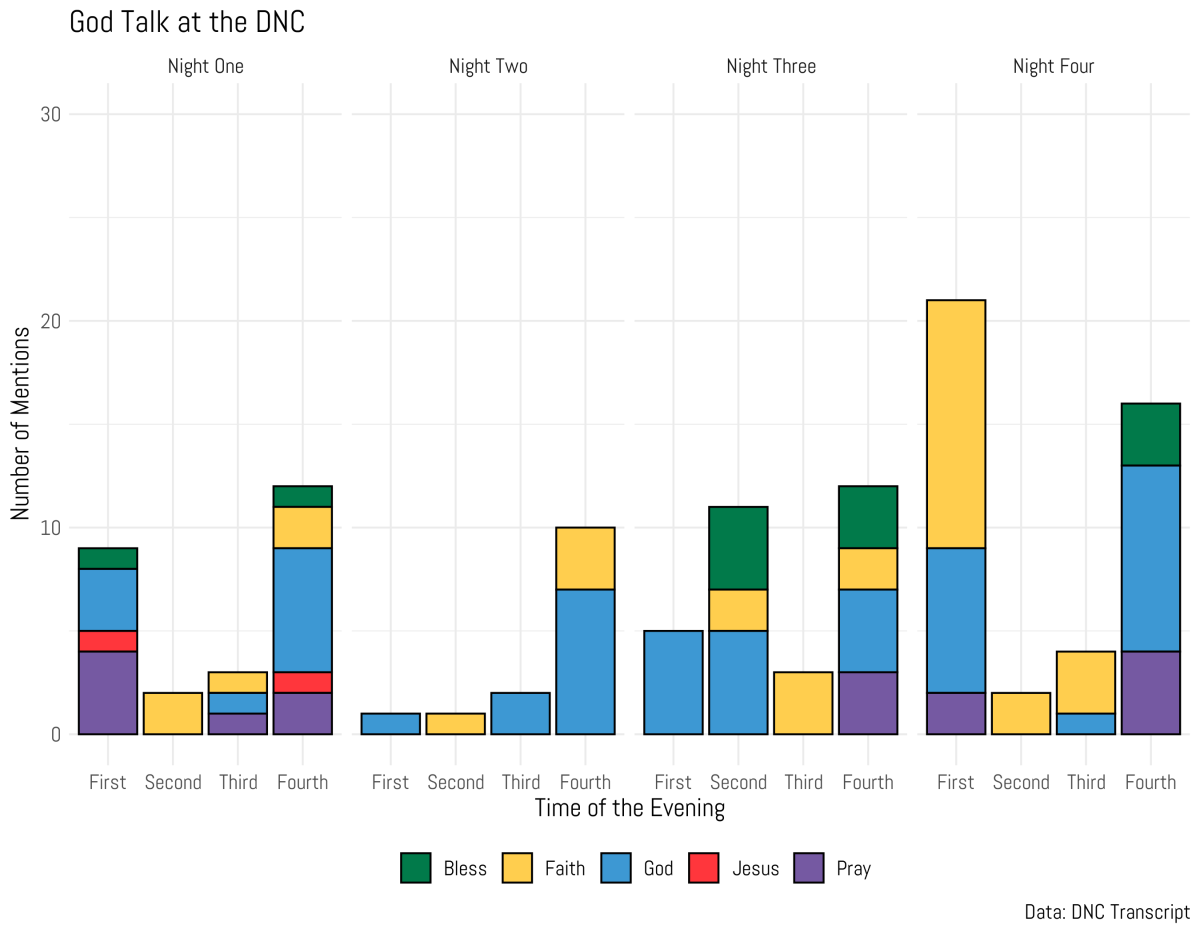

The debate is also a chance for voters to hear how Trump and Biden speak about their political priorities and motivations. Both have been campaigning to draw in voters of faith, including evangelicals. The party conventions held last month offer a glimpse at how they have employed religious language in the race. Faith references came up throughout the Republican National Convention in August far more often than at the Democratic National Convention, which had been held the week before.

But when it came to the remarks from the candidates themselves, the trend reversed. Biden, a lifelong Catholic, made faith a bigger part of his speech than Trump did.

Ahead of the debate, I took a closer look at the kinds of religious terms we’ve seen from both platforms so far, based on an analysis of 2020 convention transcripts.

References to God were most common at both party conventions, followed by mentions of faith, blessing, prayer, and Jesus—who occasionally came up by name at the RNC but almost not at all at the DNC.

There are limits to text analysis to keep in mind—this method won’t identify religious language that is not explicit, and it also counts all words equally. Thus, Mike Pence quoting a long passage from the Bible that uses God’s name once counts the same as Joe Biden ending his speech by saying, “God bless America.” But, despite these constraints, it offers an unbiased glimpse of the most direct religious references evoked by the campaigns.

For the Republicans, religious language was fairly prevalent across the first three nights of the convention. Most 30-minute blocks of programming contained at least 15 references to religious imagery with “God” and “bless” leading the way—obviously “God bless America” being a common sentiment and sendoff for speakers.

However, the last night of the Republican National Convention saw a much different pattern.

That evening, Trump offered his acceptance speech. He made fewer references to God than the other Republican speakers. He invoked God on three occasions, including a reference to “all children, born and unborn, [having] a God-given right to life,” and mentioned “faith” once.

While Biden’s campaign has offered a more robust faith outreach effort than Hillary Clinton in 2016, the party as a whole is still more much muted in their religious references than the Republicans. For instance, there was more religious language in the first 30 minutes of the first night of the Republican National Convention than in the entire two hours of the DNC’s opening night.

Again, the pattern shifts on the final night of the convention. Biden referenced our purpose “as God’s children” and spoke multiple times about the “soul of America” or “soul of this nation.”

Yet it was Delaware Sen. Chris Coons, a graduate from Yale Divinity School, who was responsible for most of the religious language as he testified to the sincerity of the former vice president’s convictions.

“For Joe, faith isn’t a prop or political tool,” said Coons. “I’ve known Joe about 30 years, and I've seen his faith in action. Joe knows the power of prayer, and I've seen him in moments of joy and triumph, of loss and despair, turn to God for strength.”

The convention also had a spike in faith language from non-Christian voices, with final prayers delivered by Rabbi Lauren Berkun and Imam Al-Hajj Talib Abdur-Rashid to end the evening’s festivities.

While the RNC clearly had a higher frequency of religious language, it was also specifically directed toward a Christian audience.

The word Christ was invoked six different times, and Melania Trump referred to Christianity specifically in her speech. On the other hand, the Democrats never mentioned the word Christ during the four nights of their convention.

This time, as Trump and Biden take the stage in Cleveland, it’ll be up to them whether faith comes up in their responses. Based on what we heard from them during the party conventions, it seems unlikely that either candidate will go out of his way to invoke religious imagery in the debates.

It would be a tremendous deviation from prior behavior to see either candidate invoke theological positions or scriptural references to support his positions on hot-button issues (as Episcopalian Pete Buttigieg did during an early Democratic debate last year).

The pattern of largely leaving religious references out of the presidential debates follows what happened in 2016, when The Atlantic deemed one between Trump and Clinton “America’s first post-Christian debate.”

In 2020, appeals to religious voters are more likely to be couched in the language of policy stances than faith itself.

Ryan P. Burge is an assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University. His research appears on the site Religion in Public, and he tweets at @ryanburge.