In this series

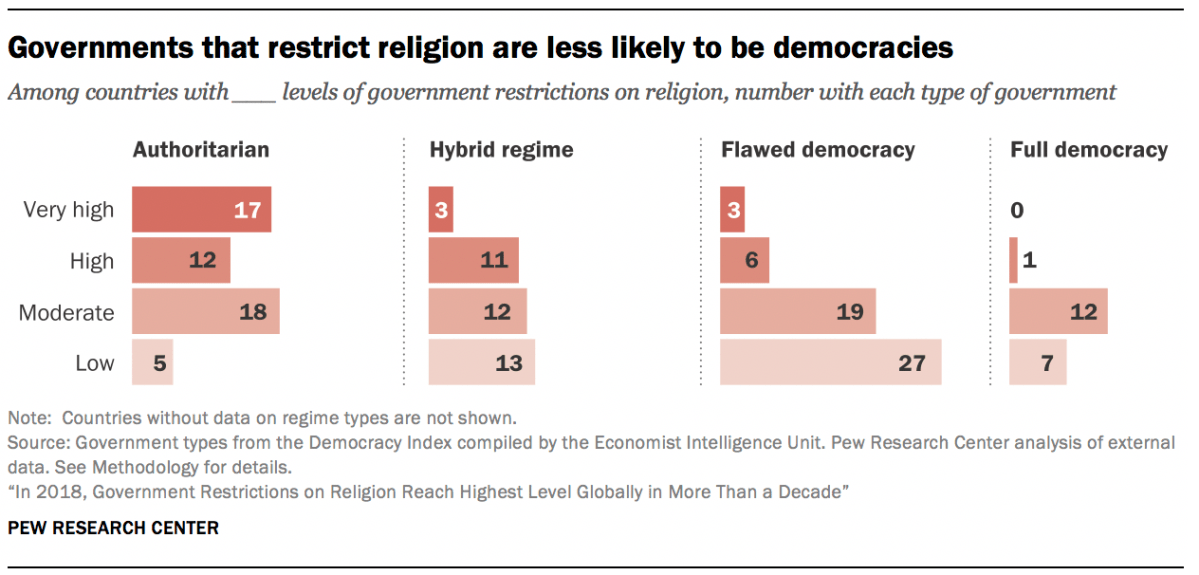

Dictators are the worst persecutors of believers.

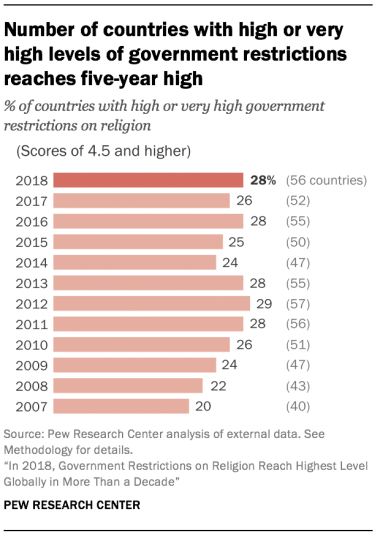

This perhaps uncontroversial finding was verified for the first time in the Pew Research Center’s 11th annual study surveying restrictions on freedom of religion in 198 nations.

The median level of government violations reached an all-time high in 2018, as 56 nations (28%) suffer “high” or “very high” levels of official restriction.

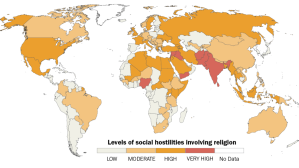

The number of nations suffering “high” or “very high” levels of social hostilities toward religion dropped slightly to 53 (27%). However, the prior year the median level recorded an all-time high.

Considered together, 40 percent of the world faces significant hindrance in worshiping God freely.

And the trend continues to be negative.

Since 2007, when Pew began its groundbreaking survey, the median level of government restrictions has risen 65 percent. The level for social hostilities has doubled.

Over the past two weeks, Christians prayed for their persecuted brethren around the world.

Launched in 1996 by the World Evangelical Alliance (WEA), the International Day of Prayer (IDOP) for the Persecuted Church is held annually the first two Sundays in November.

This year’s campaign was called One With Them.

“Them” is the 260 million Christians worldwide who face persecution, according to Godfrey Yogarajah, executive director of the WEA Religious Liberty Commission. Eight Christians are martyred for their faith each day.

But Christians are not the only ones who suffer.

Ahmed Shaheed, UN special rapporteur for freedom of religion and belief, said that of the 178 nations that require religious groups to register, almost 40 percent apply it with bias.

“The failure to eliminate discrimination, combined with political marginalization and nationalist attacks on identities,” he said, “can propel trajectories of violence and even atrocity crimes.”

In addition, 21 nations criminalize apostasy.

“Faith has to be voluntary,” Shaheed told CT in an interview conducted in April. “There is no value in faith if it is not free.”

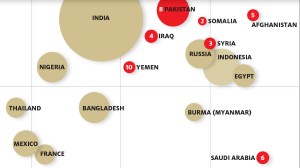

The worst offenders are familiar.

Among the world’s 25 largest nations, India, Egypt, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Russia had the highest overall levels of both government restrictions and social hostilities.

But while not all of these are autocracies, Pew noted that authoritarian governments lead the way.

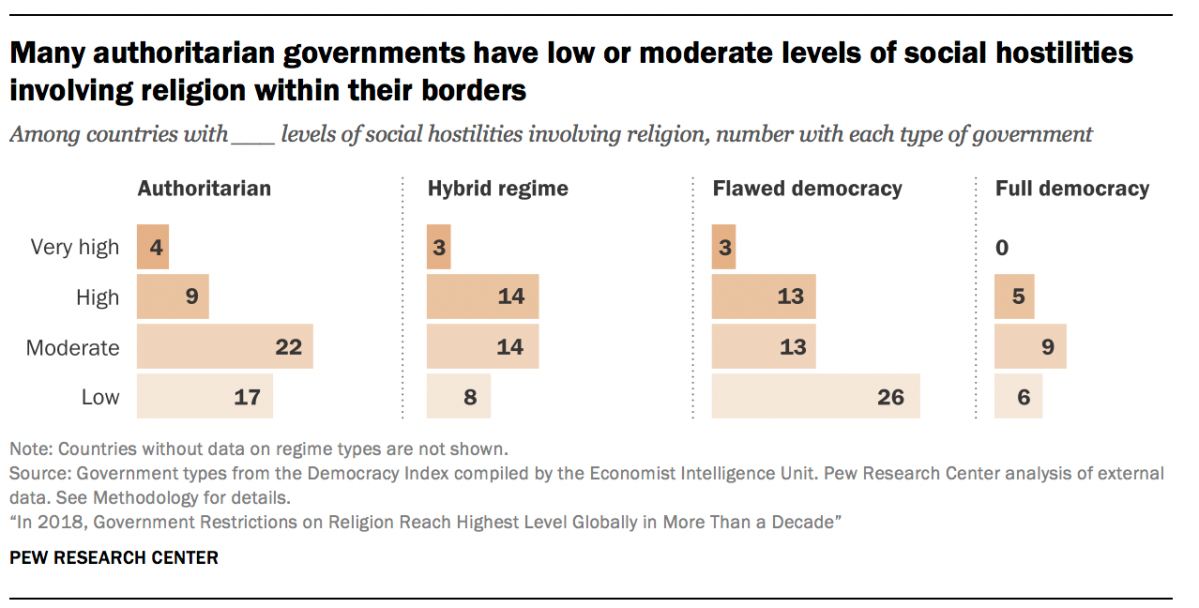

Using terminology from the Democracy Index, of the 26 nations ranked as “very high” in government restrictions, 65 percent are authoritarian. And of the 30 nations ranked as “high,” 40 percent are authoritarian, while 37 percent are a hybrid regime with some democratic tendencies.

Denmark was the only full democracy, after banning the Muslim face veil.

Social hostilities are not as straightforward.

Of the 10 nations ranked as “very high,” four are authoritarian, three are hybrid, and three are flawed democracies—India, Israel, and Sri Lanka. And in the 43 nations ranked as “high,” 21 percent are authoritarian, 14 percent are hybrid, 30 percent are flawed, and 12 percent are full democracies.

These included Germany, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

Some authoritarian states with high restrictions on religion were successful in tampering social hostilities, such as Eritrea and Kazakhstan. Others, like China, Iran, and Uzbekistan, still recorded moderate social hostilities.

“High levels of government control over religion may lead to fewer hostilities by nongovernment actors,” stated Pew researchers.

But it has not stopped the growth of the church.

The WEA noted that in China, the Protestant church has grown from 1.3 million members in 1949 to at least 81 million members today. The Catholic Church in China has grown from 3 million members to over 12 million during the same 50-year period.

Shaheed, meanwhile, highlighted the 1 million Uighur Muslims held in Chinese “reeducation camps,” as well as China’s restrictions on Falun Gong and Tibetan Buddhists.

But the region with the highest median rank in terms of government restrictions is the Middle East and North Africa (MENA): Eighteen of its 20 countries (90%) rank “high” or “very high.”

Shaheed said 4 are among the 12 nations that criminalize apostasy with the death penalty.

The WEA noted that persecution is better regarded as a consequence of church growth rather than its stimulant. Iraq and Syria are among the Middle East nations where the church has shrunk in size over past decades.

“While persecution brings disaster, it is nevertheless a phenomenon that lies within the sovereignty of God,” stated an IDOP study on Acts 8.

“Persecution does not define the destiny of the church. God does.”

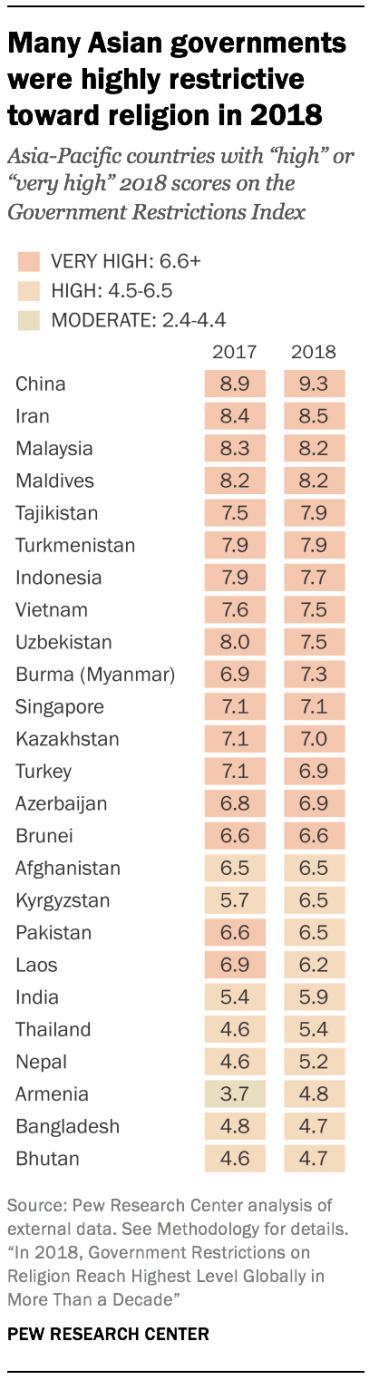

After MENA, Asia-Pacific was the second-highest region in terms of government restrictions. Half of its 50 nations qualified, but it also represented the largest median increase. On Pew’s 10-point scale, China (9.3) and Iran (8.5) led the region, while Tajikistan, India, and Thailand recorded new highs.

Shaheed highlighted Thailand’s surveillance of Muslim groups, as well as Vietnam’s denial of citizenship to Hmong Christians.

There were no evangelical Christians among the Hmong in 1989, the WEA said. But today there are over 175,000, despite “brutal” oppression.

“Persecution does not thwart the purposes of God,” stated the IDOP study.

“Instead it can serve in establishing it, through the obedience and witness of the believing community.”

The Pew report noted that worldwide, social hostilities ticked downward in its most recent survey.

But as with the government rankings, MENA was highest with 55 percent of its nations suffering “high” or “very high” social hostilities. Europe was second with 36 percent, and Asia-Pacific was third with 28 percent.

The Americas ranked lowest in both categories.

And of the world’s 25 largest nations, Japan, South Africa, Italy, Brazil, and the United States had the lowest overall levels of both government restrictions and social hostilities.

Three nations were newly added to the “very high” government restriction list: Iraq, Western Sahara, and Yemen. Four nations were removed: Comoros, Laos, Pakistan, and Sudan, though all remained “high.”

Repeat members from 2017 include: Algeria, Azerbaijan, China, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Myanmar, Turkey, Uzbekistan, and Vietnam, among others.

Libya and Sri Lanka, meanwhile, were added to the “very high” social hostilities list, while Bangladesh and Yemen were removed yet remained “high.”

Repeat members from 2017 include: Central African Republic, Egypt, India, Iraq, Israel, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Syria, among others.

Meanwhile, Christianity and Islam remain the most harassed religions worldwide, in 145 and 139 nations, respectively. These numbers have risen from 107 and 96 nations, respectively, in 2007.

MENA is the worst region for both. Christians suffer government restrictions in 95 percent of its countries, and social hostilities in 75 percent. Muslims, including Muslim majorities, suffer restrictions in 100 percent of MENA nations and hostilities in 65 percent, respectively.

Jews, harassed in 88 nations, are the only religious group to face more societal hostilities than government restrictions.

Buddhists suffered the highest increase in global harassment, from 17 nations in last year’s report to 24 in this year’s report.

The unaffiliated, including atheists, agnostics, and humanists, had the largest decrease, from 23 nations last year to 18 this year.

Shaheed stressed that proper religious freedom advocacy needs to represent all belief systems. He was pleased with how US officials in the State Department and Ambassador-at-Large Sam Brownback made this a priority.

He also praised the WEA for being “very inclusive.”

“Beyond praying for Christians, IDOP has highlighted the plight of people who belong to other religious groups and of adherents to non-religious worldviews,” wrote Thomas Schirrmacher, newly elected secretary general of the WEA, for IDOP.

“So even though it is a Christian worship service, several governments have taken up the topic of religious freedom for all after years of IDOP in their country, as they know that the topic will not go away.”

Which is the same patience Shaheed shows through the UN.

“Human rights work is like dropping water on a stone,” he told CT. “Given enough time, it will eventually break it down.”