After three years of anticipation—and dread—President Trump announced the launch of his “Deal of the Century” to achieve peace between Israel and Palestine.

With Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu at his side, he outlined details for a proposal that would recognize a Palestinian state following extensive land swaps and security arrangements.

Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas was not present, having broken off communication with the White House following several US decisions deemed biased toward Israel.

Abbas immediately rejected the plan, which Palestinians had long declared “dead on arrival.”

But Netanyahu’s acceptance was enthusiastic, declaring himself willing to begin negotiations with the Palestinians on such terms. A day earlier, Netanyahu’s challenger Benny Gantz also signaled his party’s agreement with Trump’s proposal.

With three Arab states lacking a peace treaty with Israel in attendance—Oman, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE)—Trump hopes there will be a regional push to implement his plan.

And with $50 billion promised as investment for the nascent Palestinian state, the president believes all the necessary pieces are in place.

“All previous generations from Lyndon Johnson tried and bitterly failed,” Trump said. “But I was not elected to do small things, or shy away from big problems.”

Alex Wong / Getty Images

Alex Wong / Getty Images

It only required he approach peace in a “fundamentally different” manner.

No Arab or Israeli would be uprooted from their home. This guarantees the preservation of all existing Israeli settlements in occupied Palestinian territory.

Jerusalem would remain the undivided capital of Israel. At the same time, on the other side of the separation wall, eastern Jerusalem would become the capital of the Palestinian state, receiving a US embassy.

The White House

The White HousePalestinian residents in Jerusalem on the other side of the wall would be given the option to become Palestinian citizens, Israeli citizens, or remain as permanent residents.

Israel would exercise security over Jerusalem’s holy sites, while Jordan would maintain its status quo authority over the Temple Mount and al-Aqsa Mosque. Muslim pilgrims would be guaranteed access.

Palestinian refugees would be barred from Israel but processed in limited numbers into the new state of Palestine. Pending approval, the rest would be given the option of naturalizing into their nations of residence or relocating elsewhere. Funds would be set up to facilitate.

Israel would receive land in the Jordan Valley to address security concerns. Palestine would receive land in the Negev Desert for industrial development. All international access would be controlled by Israel, with corridors created for ease of domestic transportation to non-contiguous territory.

For the first time, a conceptual map of Israel’s borders was released.

The White House

The White HouseIsrael would guarantee a four-year freeze on all settlements outside the scope of this plan, while Palestinian leadership studies the proposal and moves to implement it.

To do so, it must demilitarize Gaza and stop payments to the families of terrorists. Domestic laws must reflect human rights and freedom of religion.

“It is time for the Muslim world to correct the mistake it made in 1948, when it attacked rather than recognized Israel,” Trump said. “If you choose the path to peace, we will be there to help every step of the way.”

Netanyahu also referenced 1948, the year of Israel’s independence, in comparing Trump to then-US President Harry Truman. History would look back on this day similarly, he said, as Trump extended Israel’s sovereignty over “Judea and Samaria,” his favored term for the West Bank.

“You have been the greatest friend Israel has ever had in the White House,” he said. “There have been others, but it’s not even close.”

Joel Rosenberg, co-founder of the Alliance for the Peace of Jerusalem, was impressed.

“It was an excellent rollout ceremony,” he said, “dramatic, surprising—and controversial.”

Withholding full judgment until he reads the full 181-page plan, the bestselling author of End Times-inspired political fiction said that Trump’s plan gave Israel almost everything they wanted, but was also “generous” to the Palestinians.

On that count, it may complicate domestic politics for Trump and Netanyahu alike. Though some Christian Zionists oppose a two-state solution, Rosenberg believes many evangelicals will be “enthusiastic.”

But Israel’s settler community “wants everything,” Rosenberg said.

More than 600,000 Israeli Jews live in settlements scattered across the West Bank and east Jerusalem. Their main political body has rejected the deal, as have a few Netanyahu allies who have called for immediate annexation.

“They are very angry, and Bibi could have a problem on his right,” he said. “He might now surprisingly have to make a deal in the center, with Gantz.”

Trump’s plan, previously delayed due to repeated Israeli elections that failed to secure a ruling majority coalition, now heads to its third re-run on March 2.

But Rosenberg believes the Deal of the Century had two primary goals, anticipating Palestinian rejection. One, to be a creative, credible, compassionate approach to peace—just in case.

And two, to appeal to Arab regional leaders who wish to make peace with Israel but are tied by the Palestinian issue. If Abbas rejects a good plan, they may proceed without him.

“Seeing three Arab Gulf leaders at the ceremony,” Rosenberg said, “he just might have succeeded in threading the needle.”

Perhaps Palestinians will see the promise of a state and economic development and reject their rejectionist leadership, he wonders. Their situation is sad, and perhaps divinely so.

“Palestinian leaders will huff and puff, but they look ridiculous and their people are suffering,” Rosenberg, an evangelical of Jewish descent, said.

“But as I read in the book of Exodus, I can’t help but wonder if God has just hardened Abbas’s heart.”

Not at all, according to Salim Munayer, head of the Jerusalem-based Musalaha reconciliation ministry. This past year, he has held many sessions discussing peace between Muslims, Christians, and Jews.

“From our discussions, the issues are clear: Israelis want security, and Palestinians want justice,” Munayer said. “No Palestinian leader can accept this deal, because it doesn’t meet our basic needs.”

East Jerusalem should be their capital, he said, but left unsettled is the question of Jewish settlers moving into Arab neighborhoods. Refugees deserve the right of return, but are left out of this proposal. And the Jordan Valley is essential for Palestinian population expansion, agricultural development, and vital water supply.

Israel already controls security along the border, it does not need to appropriate the land, Munayer said.

But beyond the details, the “Deal of the Century” lacks the moral framework to win Palestinian support. In successive steps over the past years to move the embassy to Jerusalem, cut humanitarian funding, and no longer consider settlements as occupied territory, the US has lost all trust as a moderator, he said.

“If one side humiliates the other, there can be no agreement,” Munayer said. “Israel is eating the pizza, while saying to the Palestinians, ‘Let’s negotiate slices.’”

This fits also into Israel’s domestic context, he said. The plan was released on the same day Netanyahu was indicted on corruption charges.

Real peace must come through grassroots reconciliation, and not be imposed from the top, Munayer said. But worse, Trump’s plan comes wholly from the outside.

Overall, he had little emotional response to the proposal—that came months earlier, when the US cut funding to Palestinian hospitals.

“I didn’t have a lot of expectations, it was no surprise,” Munayer said. “It used to be one-sided before, but never this extreme.”

Daoud Kuttab, a Palestinian journalist and secretary of the Jordan Evangelical Council in Amman, read the plan in full and said its contents and its rollout “sounded more like a surrender dictate than a peace plan.”

“The fact that of 13 million Palestinians, the Americans couldn't find a single one to attend [the rollout] spoke volumes in its one-sidedness,” he told CT.

Kuttab most approves of the plan’s Gaza-West Bank tunnel, which would end Israel’s separation of the two territories. He most opposes its lack of autonomous borders. “Despite using the words Palestinian state, the plan gives Palestine no real independence and allows Israel control over borders, over the air and sea, and [Israeli security forces] can enter Palestine at any time they choose.”

“It is a surrender document that will lay the grounds for Palestinians to continue to live under Israeli discrimination,” he said. “It is a death to the two-state solution, and will do nothing to help the peace process. This is a formula for further violence and unrest.”

Hanna Massad, a Palestinian pastor who led Gaza Baptist Church for 12 years and returns regularly, said the plan is “unfair” and fails to meet either Palestinian “ambitions” or UN resolutions. It contains “no justice,” which for him means Jerusalem for a capital and a return to 1967 borders.

Massad still has the documents showing the land his family lost in Israel. “We keep it safe, so that at least one day we might receive compensation.”

“It breaks your heart to see the poverty and suffering of the people in Gaza,” he told CT. “As Palestinians, we have also done bad things against the Israelis. But because we are the weaker party, we suffer more.”

“My father told me he wished to see peace in his lifetime,” Massad said. “Now, I wonder if my children will see it.”

“We hope for fairness and justice for all sides,” he said. “But we hope only in the Lord.”

Gerald McDermott, Anglican Chair of Divinity at Beeson Divinity School who recently wrote The New Christian Zionism: Fresh Perspectives on Israel and the Land, said the plan is “a realistic opportunity for a two-state solution,” given its offer of “huge economic help and a Jerusalem capital.”

He is not surprised by Abbas’s rejection, but instead is struck by regional reaction. “For the first time, there is considerable Arab support for an American-initiated deal,” he said, naming the UAE, Oman, Bahrain, and Egypt. “All of these states are tired of Palestinian rejectionism.”

“Like any political compromise, it will cause pain on all sides,” McDermott told CT. “Netanyahu, for example, is suffering major criticism from the Israeli right.”

However, he said, “There is no theological reason why Israel cannot compromise with Arabs. Both Abraham and Isaac did.”

Yohanna Katanacho, a Palestinian pastor and academic dean at Nazareth Evangelical College, said it doesn’t take a “prophet” to know Trump’s plan is “destined to failure.”

“Trump is trying to address a difficult problem but he is not addressing it from the perspective of humility,” he wrote for Come and See, a Nazareth-based Christian website. “Such humility does not ignore UN resolutions, Palestinian input, Palestinian citizens of Israel, and justice.”

“This raises a question concerning peacemaking,” Katanacho wrote. “Political peace is no doubt needed, but it cannot be accomplished without a solid moral foundation rooted in justice, equality, and love.

“At best, Trump’s proposal is seeking to prevent wars. It does not promote a lasting peace,” he wrote. “Trump’s plan does not promote a politics of love but of fear from Palestinians. Love respects, listens, and suffers for the sake of justice. Love does not seek deals, but healthy relationships.”

Lisa Loden, the Messianic Jewish co-chair of the Lausanne Initiative for Reconciliation in Israel–Palestine, acknowledged the plan is “creative” but not viable because it is a bilateral proposal between the US and Israel, not between the Israelis and Palestinians.

“My reaction was one of deep sadness, pain, and grief at what this plan could mean for the people of this region,” she told CT. “The continuation of Israeli control over Palestinian lives, and—according to the plan—the ongoing militarization of this and future generations of Israelis who would continue to exert that control, is an untenable situation resulting in collective trauma for both sides.

“The non-viable and non-contiguous Palestinian state described in the plan and visualized in the accompanying map are unrealistic,” she said. “I was struck by the total absence of any Palestinian city name on the map.”

Loden expects current evangelical supporters of Israel will “generally be quite pleased” with the plan. “A significant number will think that this plan does not go far enough, and that ultimately all the land should belong to Israel,” she told CT. “On the other side, evangelicals who are supportive of the Palestinian people will be devastated by the almost unilateral support of Israel’s positions.”

Joel Chernoff, general secretary of the Messianic Jewish Alliance of America (MJAA), said whether the “Deal of the Century” (DOC) is viewed positively or negatively depends on one’s “perspective and primary objective.”

“If the Palestinian’s primary objective for an agreement with Israel is peace and prosperity, this proposal is a great opportunity and a $50 billion boondoggle one would be foolish to reject,” he told CT. “However, if your objective is an independent state with defined borders that the Palestinians control … and secure with their own military, the DOC will be viewed as a humiliating surrender to the hated Zionist state.”

Chernoff also believes the plan’s pre-conditions are “non-starters.” “First, our Arab cousins have never been willing to recognize and affirm the Jewish state as legitimate. Second, Hamas will never agree to voluntarily disarm and de-militarize Gaza contrary to the wishes and agenda of their puppet-master, Iran,” he said. “The $50 billion for development, though very generous, is really irrelevant when the Islamic terrorist groups and nations backing them desire the destruction of the Jewish state and reclamation of its land for Allah. This is a Muslim theological imperative.”

Martin Accad, chief academic officer at Arab Baptist Theological Seminary in Beirut, was interested to learn the new plan’s details, yet skeptical.

“The fact that this plan was different made it interesting to me,” he told CT. “Seventy years of similar plans have not led anywhere. Could this one provoke change?”

However, now that the details have been released, he sees “it is an unusual way to solve such a longstanding conflict, and it is not promising.”

Accad is disturbed by parts of the plan, as well as that only the Israelis consulted on it. The phrase “no Israeli or Palestinian will be uprooted from their home” is “basically a guarantee to Israel for its settlements,” he said. Meanwhile, the “right of return” has “basically been cancelled.”

“As a Lebanese, we know how problematic it is for the 280,000 Palestinian refugees to still be here,” he told CT. “Settling them in Lebanon is completely out of the question in our political calculations.”

Accad fears if the plan is not refined, it will lead to “something far worse” than the current status quo. “Now that there is an agreement on one side, the four years opens an interesting window,” he said. “If someone would work intensely with the Palestinians, listening to their concerns as [Jared] Kushner has with the Israelis, perhaps this can be brought into the existing framework. But I don’t know if this is even possible, as the plan is unilaterally designed to fit Israeli needs.”

John Hagee, the founder and chairman of Christians United for Israel (CUFI) who attended the White House rollout, praised President Trump for being “the most pro-Israel president in US history.”

“This plan reflects that tradition and is the best peace proposal any American administration has ever put forth,” stated Hagee. “The President’s vision ensures Israel’s defensible borders, a united Jerusalem, sovereignty over biblical holy sites, and provides an opportunity for the Palestinians to choose peace.

“CUFI, as we have since our founding, stands with the decisions of the democratically elected government of Israel,” he stated. “We hope the Palestinian leadership will not miss yet another opportunity for peace in the region.”

Todd Deatherage, cofounder and executive director of Telos Group, which seeks to build a “pro-Israeli, pro-Palestinian, pro-peace movement,” said the plan is not a map for peace but merely a “rearrangement” of the status quo in an “unabashedly rightwing Israeli voice.”

“This American effort is entirely lacking in humility and misses the mark in several ways,” he told CT. “The conflict is much more than a real estate deal.

“It’s for sure a dispute over who has the deepest connection to the same geography, but it’s also a battle of multiple narratives, of different experiences, of identities,” he said. “And to embrace and affirm only one of those—as this does in both tone and substance—can hardly be taken as a serious effort at diplomacy or peacemaking.”

“True peace is not made when powerful parties gather and dictate terms to their enemies,” Deatherage said. “The hard work of peacemaking requires listening, tough choices, hard conversations, and mutual sacrifice.”

“Where bad things have happened over generations, it requires truth and justice, and a process for reconciliation. And where there’s a power imbalance, it requires risk,” he told CT. “A real friend to Israel would help them do the hard things that are in their own long-term interests.”

Wissam al-Saliby, the Geneva-based advocacy officer for the World Evangelical Alliance and a Lebanese evangelical who has worked extensively in his homeland’s Palestinian camps, pointed to the writing of a West Bank rabbi, Hanan Schlesinger, who last year compared Egypt’s enslavement of the Jewish people to Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians today.

“We may disagree on the solution to the conflict: one-state, two-state, and what each of these notions mean,” Saliby told CT. “And we may disagree on what place the current State of Israel occupies in God’s plans.

“But we cannot disagree that the ‘Deal of the Century’ enshrines the injustice that Rabbi Schlesinger describes, rather than lay the foundations for a just and permanent peace,” he said. “We cannot disagree that the proposed island nation of Palestine is non-viable, non-sovereign, and will not bring healing for past injury, hope in the future, or hope in a dignified life. And economic incentives do not provide for dignity, less so for human rights and for freedom.”

Saliby noted how Israeli settlements have “rendered impossible” the promise made in the 1994 Oslo Accords of a Palestinian state. That unfulfilled promise makes it hard for Palestinian leaders to trust the new promises in the new plan.

“The Deal of the Century seems to enshrine the injustice of the current situation,” he told CT, “and this can never achieve peace, even if the Arab nations and the whole world accepted it.”

Ibrahim Nseir, Syrian pastor of the Presbyterian Church of Aleppo, said the plan is overly influenced by the coming elections and ongoing trials in both Israel and the US.

“Whenever you hear about an overture of peace, you will be happy,” he told CT. “But when it is forced, you cannot be comfortable.”

“You cannot make peace this way. Peace is not a decision. It is a process, and a way of walking together.”

“This is more of a business agreement than a peace proposal,” said Nseir. “Where is justice? … There must be confession of the sins of the past, but here no one says they did anything wrong.

“Christ paid for our sins on the cross. But who in this plan will pay the price for the sins of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict?”

CT reported in April on the “red lines” of the peace plan, as expressed by 11 American and Arab evangelical leaders.

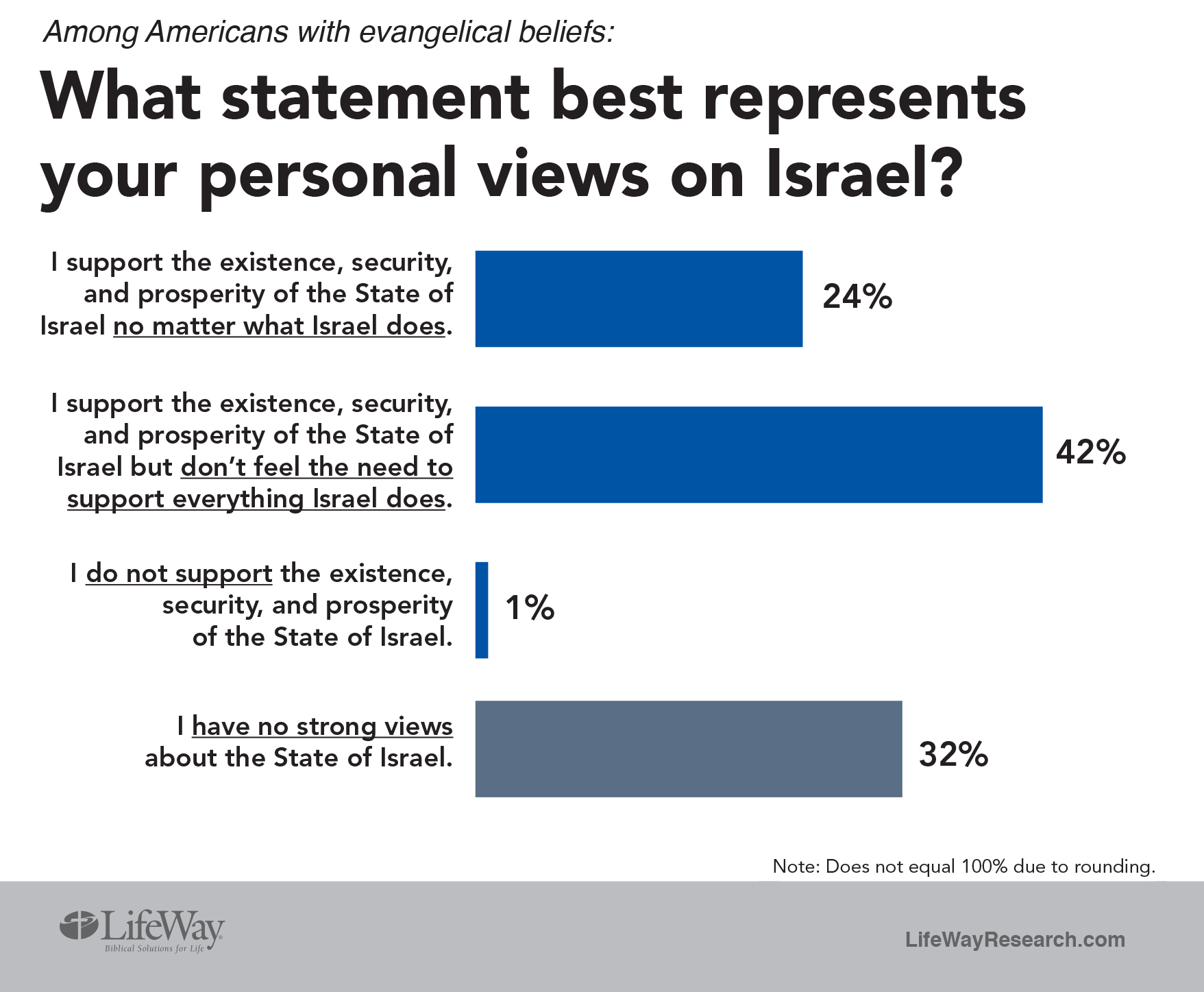

According to a 2017 survey by LifeWay Research, 31 percent of Americans with evangelical beliefs believe Israel should not sign a peace treaty with Palestinians that would establish their own sovereign state. Nearly 1 in 4 (23%) believe they should, while 46 percent are not sure.

Correction: In an earlier version of this story, a source mischaracterized CUFI’s John Hagee as having “spoken clearly against” a two-state solution. CUFI told CT that Hagee has “never taken a position” on a two-state solution.