Churchgoers are most likely to say they don’t know whether their pastor is a Republican or a Democrat—and many preachers believe that’s a good thing.

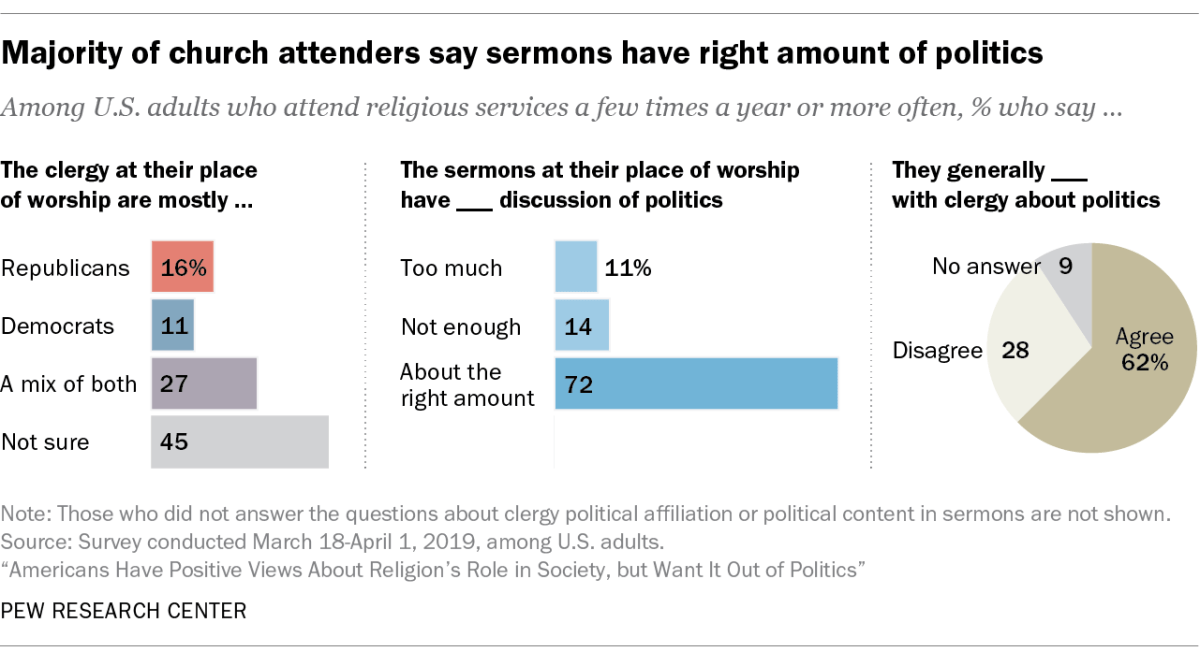

A new survey by the Pew Research Center finds that almost half (45%) of people who attend services at least a few times a year are “unsure” of their clergy’s partisan leanings. Over a quarter (27%) say their clergy are a mix of both parties, while 16 percent say they lean Republican and 11 percent say they lean Democrat.

The job of the pastor is to help churchgoers see that “neither party has a corner on true Christianity, and neither party is working out the values of Christ’s kingdom in its fullness,” said Bill Riedel, pastor of Redemption Hill Church in Washington, D.C.

Riedel told CT he was pleased to see that almost half of churchgoers do not know their pastors’ political leanings, but he would like that percentage to climb even higher. While pastors have a right to their political opinions, Riedel said, pastors should, like the Apostle Paul in Corinth, be willing to set aside their rights for the sake of the gospel.

“To be a Christian doesn’t mean you ascribe to a particular secular partisan ideology,” he said. “I don’t think pastors should be fake about who they are either. It’s an entire grid of how we think about politics that ought to be changed.”

When politics does come up from the pulpit, a majority of those in the pews (62%) say they agree with their leaders. The political overlap is particularly strong among evangelical Protestants, three-quarters of whom (76%) say they agree with their pastor’s political opinions, the survey found.

Some Christians have spoken up for the right for pastors to endorse political candidates, and President Donald Trump often talks about repealing the Johnson Amendment to free churches to take a stand without losing their tax-exempt status.

But overall it’s an unpopular position; Pew found last fall that most Americans (63%) want churches and other houses of worship to stay out of political matters, and more than three out of four (76%) say they should not come out in favor of a political candidate. As CT reported, Protestants in the historically black churches and evangelical Protestants are the only major religious groups that favor church endorsements.

“I deliberately avoid using language that is too precise,” Brandon Washington, preaching pastor at The Embassy Church in Denver, told CT last year. “You’ll never see us endorsing a candidate or anything like that.”

“My decision to not make political statements or not align with a political party from the platform does not keep me from addressing matters that I believe have become politicized,” including abortion and racism, Washington said.

While few Christians heard political endorsements from the pulpit back in 2016 (Pew found that just 1 percent of churchgoers said their pastors spoke favorably about Donald Trump during the campaign, compared with 6 percent who said they spoke favorably of Hillary Clinton), there’s new momentum around political civility this election year.

“Evangelical pastors must recognize that political diversity frequently is present within churches,” said Scott McConnell, executive director of LifeWay Research. “If civility across these differences is not actively fostered, it can hurt the mission of the church. This has already been evident as many young adults point to political differences as a reason they stop attending church.”

Riedel thinks the problem in 2016 was that many pastors believed they could avoid politics and just preach the gospel. “The more heated things got … people were unprepared to think about Christian unity across political spectrum,” said the Redemption Hill pastor, whose congregation includes government staffers from both political parties. “The past two years have shown us that partisan rhetoric falls short. Christianity has a lot to say to both sides of the aisle.”