Most researchers studying religious trends among young people tend to focus on what’s making younger Americans walk away from religion. Some have emphasized life course transitions such as leaving home, going to college, or becoming sexually active. Others have examined frustration with politics. And still others have rightly pointed out that younger Americans are increasingly raised him homes where they’re no longer exposed to religious faith in the first place.

In a recent study, we decided to explore one factor that might contribute to young people staying in their faith: undergoing a traditional religious “initiation rite” like believer’s baptism, first communion, or bar mitzvah.

Scholars of religion have always been fascinated with rites of passage and particularly what they accomplish for the group itself. The collective benefits are obvious. When we celebrate the entrance of new members into our community of faith, we’re collectively reminded about our common heritage, our core doctrines, and our eternal bond with one another.

The possibility that these rites of passage might have a long-term impact on the individuals themselves can seem so self-evident that it often goes unquestioned. We decided to test how powerful that impact might actually be.

Using data from the National Study of Youth and Religion, a nationally representative panel study of young Americans, our study looked at participants at two points in time: when they were ages 13–17 and one decade later when they were ages 23–28. Depending on their religious affiliation as teens, the survey asked if they had been confirmed or baptized, not including infant baptism (if Protestant); had a bar/bat mitzvah (if Jewish); had taken First Communion (if Catholic); or if they had undergone another religious rite of passage or public affirmation of their religious faith.

We compared American teenagers who had undergone any of these religious rites of passage with those who had not in order to see whether those who had undergone a rite of passage were (1) more or less religious and (2) more or less likely to remain affiliated with their religious faith by the time they were in their mid-twenties.

Our study showed that participants who had undergone any religious rite of passage during or before their teenage years did not necessarily turn out more religious than those who had not undergone a rite of passage. However, they were 30 percent more likely to stay in their religious faith.

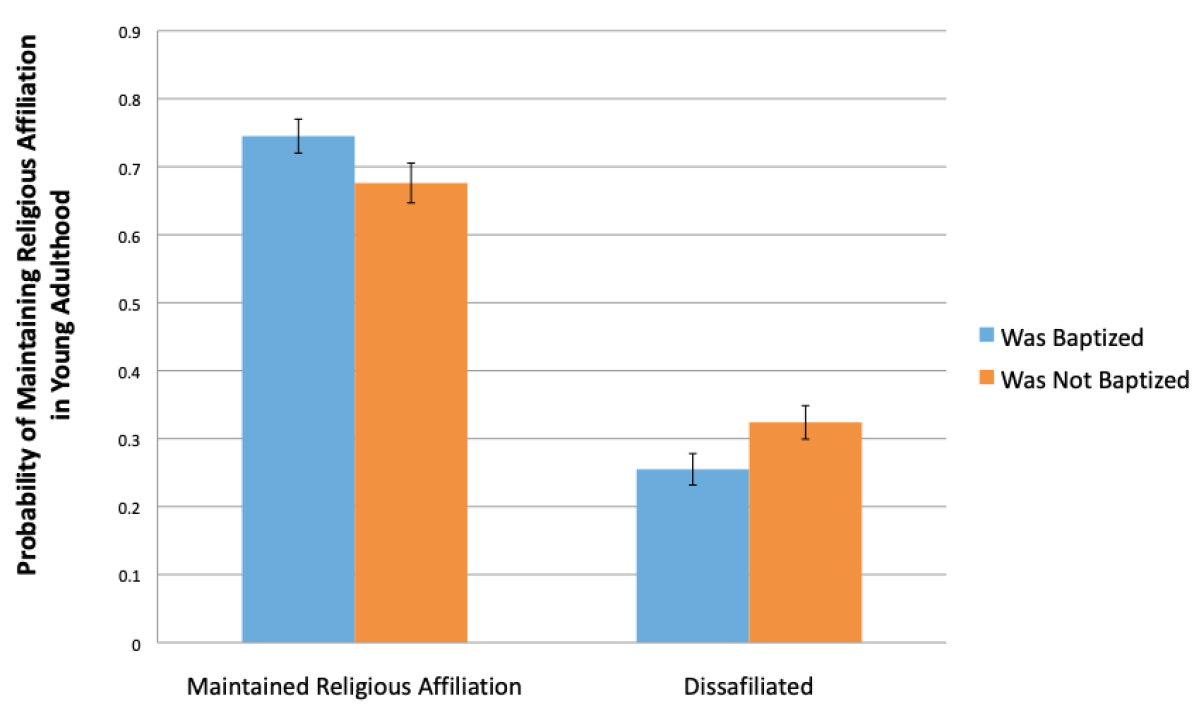

Though the pattern was the same across all religious rites and groups, the figure below shows the trend when we focus on believer’s baptism and disaffiliation among Protestant youth.

Notice first, most young people in the sample maintained their initial Christian affiliation whether or not they were baptized. But even after we accounted for teens’ initial religious commitment along with that of their parents and friends and other relevant factors, those who had undergone believer’s baptism before or during their teenage years were less likely to indicate they were “unaffiliated” in their mid-twenties.

So how does this work? The Westminster Confession calls baptism (applied to infants or adults) the “sign and seal of the covenant of grace.” What might grant believer’s baptism its “sealing” potential for young Americans?

We think the fact that baptism didn’t predict how religiously committed someone would be in their mid-twenties provides a clue. The experience of baptism doesn’t seem to have a lasting influence on one’s day-to-day religious practice, likely because that sort of influence requires a more consistent infusion of religious energy (or “grace”) from rites like regular worship attendance, or other sacraments, like The Lord’s Supper. Typically a one-time event, believer’s baptism doesn’t bind us to a certain level of faith commitment, but to a faith community. It’s about belonging and identity.

Much like the common finding that couples who are formally married are more likely to stay together than cohabiting couples who remain unmarried, for young Americans there is something binding about commitment that is declarative, formal, and public.

Consider baptism at my own church in Norman, Oklahoma. Our baptisms do not happen spontaneously without some sort of vetting on the part of parents and church leaders. There is often a formal process that includes a waiting period. The baptism ceremony is not only preceded by the affirmation of important questions, but for years now, those who are baptized provide a public reading of their personal testimony. Nervousness and tears are the norm here.

And the ceremony itself—though beautiful, given what it signifies—is messy, unnatural, and awkward. People have to change their clothes afterwards. Emerging from the water, one is greeted with thunderous applause and yells that border on the hysterical. One’s baptism, in other words is memorable. And it is social. And it is memorable because it is social.

Protestants have had long theological debates about the “efficacy” of believer’s baptism and what exactly God accomplishes through it as a “means of grace.” From what we can observe in the data, believer’s baptism accomplishes a durable social identity for young Americans. It may not make them more committed to their faith as young adults (participation of other kinds will be necessary for that), but it may help them weather some of the assaults of young adulthood such that they emerge on the other side with their faith intact.

Samuel Perry is an assistant professor of sociology and religious studies at the University of Oklahoma. His books include

Growing God’s Family, Addicted to Lust,

andTaking America Back for God

. Follow him on Twitter at @socofthesacred.