In this series

About five years ago, the Village Church of Barrington, a congregation northwest of Chicago with a $1.8 million annual budget and average weekly attendance of 600, decided to become accredited with the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability (ECFA).

ECFA—founded in 1979 to promote financial integrity in Christian ministries and avert heightened government regulation in the wake of televangelist scandals—claims nearly 2,400 members.

Those member churches and nonprofits receive more than $29 billion in annual charitable donations from 20 million donors, according to the Virginia-based ECFA.

The Village Church already allowed members to review its books and prided itself on having a transparent approach to finances. Joining ECFA would help cement its commitment to transparency.

“We thought it would give donors confidence to know that we were doing things by the book,” said David Jones, the Village Church’s senior pastor.

But now—amid scrutiny over ECFA’s years-long failure to identify financial misdeeds at Harvest Bible Chapel, a Chicago-area megachurch that fired its founder and senior pastor, James MacDonald, earlier this year—the Village Church is rethinking its relationship with the Christian watchdog group.

In December, ECFA issued a statement saying that Harvest was in compliance with its rules. Not long afterward, church officials admitted misleading ECFA.

Recently ECFA’s board terminated Harvest Bible Chapel’s membership.

“As we’ve watched this whole Harvest thing unfold, our deacons have been discussing whether to renew it or not,” said Jones, a former Harvest Bible Chapel staff member who left the megachurch nine years ago with concerns about what he describes as “power being misused” and “hypocrisy in the upper levels of leadership.”

“I think we see it as a liability rather than an asset, so why would we pay them money for something that could raise negative questions?” the pastor said.

“So our deacons have not made the final decision, but I would be shocked if they renewed it next year. The consensus seems to be getting rid of that.”

Dan Busby, ECFA’s president since 2009, referred Religion News Service’s request for an interview to a public relations firm. Karen Dye with Guardian PR + Events said Harvest Bible Chapel is “conducting an external review by a forensic accountant.”

“Out of respect for that process and until that report is public, ECFA will not be participating in any interviews,” Dye said in an email to RNS. She declined, too, to make Busby available to answer more general questions about ECFA’s history and purpose.

Harvest’s violations

In April, ECFA terminated Harvest Bible Chapel’s membership, pointing to “significant violations” of several of its financial standards. The group had suspended the megachurch the previous month after church leaders admitted “a lack of financial control and oversight” under MacDonald. In March, ECFA said that “new information” led the watchdog group to investigate whether the church had violated ECFA’s financial standards.

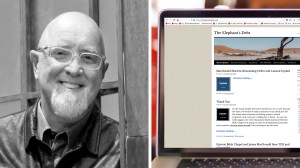

But critics, including Julie Roys, a Chicago-area freelance journalist whom MacDonald and Harvest Bible Chapel sued last year in an attempt to stop her negative reporting, say ECFA ignored “glaring improprieties” in the church’s finances for way too long.

In the defamation lawsuit filed in October in the Circuit Court of Cook County in Chicago against Roys and bloggers critical of Harvest, the church touted its approval for full accreditation by the ECFA board in September 2013, “following a full financial review by their president and treasurer.”

The church’s lawsuit petition argued that the ECFA accreditation “established with finality the immense integrity undergirding all financial matters at Harvest Bible Chapel.”

However, the plaintiffs in January dropped the lawsuit against Roys and two bloggers for a website called The Elephant’s Debt. That action came after the court ruled that documents subpoenaed in the case could be made public. Later, Roys received a $50,000 settlement, mainly to cover her legal fees, she told RNS.

In late April, with a new leadership team and elder board in place, the church apologized to Roys as well as bloggers Scott Bryant and Ryan Mahoney and their wives—who also were sued—and said the lawsuit “was a sinful violation of 1 Corinthians 6 and biblically should not have been pursued.”

Still, Roys remains dismayed with ECFA’s role—or lack thereof—in her effort to shine a light on MacDonald and Harvest Bible Chapel.

“I guess I initially expected them to be an ally,” Roys said of ECFA. “I was just stunned that there wasn’t any answering of the things that I brought up.”

In December, ECFA issued a statement vouching for Harvest Bible Chapel’s financial integrity, saying the association’s staff made an on-site visit to the church and confirmed its compliance with “compensation-setting and related-party transactions.”

“Harvest Bible Chapel is in full compliance with each of ECFA’s Seven Standards of Responsible Stewardship and remains a member in good standing in ECFA,” the statement concluded.

Four months later, in terminating Harvest’s membership, ECFA said its December statement “would not have been made if Harvest Bible Chapel had shared all crucial information with ECFA.”

The public statements by ECFA—which gives its mission as “Enhancing Trust in Christ-Centered Churches and Ministries”—have failed to satisfy Rusty Leonard, founder and CEO of the donor advocacy organization Ministry Watch, based in Charlotte, North Carolina.

“For people who are paying attention, they’ve lost a ton of credibility,” Leonard said. “It’s not just a one-time thing. We’ve had two rather gigantic blowups that came on their watch.”

Besides the Harvest case, he cited Gospel for Asia, whose membership ECFA terminated for cause in 2015, Christianity Today previously reported.

That organization later was sued over how it handled donations, with critics saying it misled donors on how their money would be used. The group recently agreed to refund $37 million in donations without admitting wrongdoing as part of a settlement with plaintiffs.

ECFA depends on funding from its members, based on the size of their budgets.

Harvest, for example, would pay roughly $10,000 a year for its accreditation, based on ECFA’s online fee schedule. However, Leonard said he has more respect for ECFA than to suggest its failure to uncover Harvest’s problems sooner had to do with relying on its membership fee.

Nonetheless, Leonard said ECFA support of Harvest was troubling.

“It looks really bad,” he said.

“From ECFA’s perspective, waiting this out, waiting for the news cycle to blow over and hoping they don’t have any more incidents pop up anytime soon, is probably their strategy,” he said. “But it would be better if they came out and acknowledged their shortcoming and said, ‘This is what we’re doing, and this is how we’re going to make sure it doesn’t happen again.’”

Bringing members into compliance

But Frank Sommerville, a Texas-based attorney, CPA and editorial adviser for Church Law and Tax, a fellow CT publication, defends the mission and purpose of ECFA.

“It’s not perfect by any means because it’s voluntary,” Sommerville said. “But the goal was to create a gold standard, for lack of a better word, for people to know that these entities, these Christian organizations, have met the minimum standards. So as a donor, you can trust them.”

ECFA isn’t in the business of revoking memberships, Sommerville said. It’s in the business of bringing members into compliance.

“Their role is, if you’re not in compliance, if it’s out of ignorance, you work with them to bring them into compliance,” Sommerville said. “I don’t see that anybody wins by just revoking their membership if they’re not in compliance.

“There’s a lot of due process to make sure that revocation isn’t taken lightly,” he added. “Some people want to criticize it, but I don’t think acting swiftly in that area is a smart business model. You want to make sure you have the facts right. You want to make sure that particular member understands where they’ve messed up or where they haven’t met the seven standards, and they can figure out if they really want to operate with integrity.”

Like Sommerville, Timothy Murphy, an Indianapolis-based CPA who works with nonprofits, including faith-based entities, voiced confidence in ECFA’s leaders, saying “they’re very much focused on what’s good for the kingdom.”

“I think my concern is whether this Harvest situation casts doubt on what they do,” Murphy said. “I think it’s important, if mistakes have been made, you own up to it—you step up and move on.”

As Sommerville sees it, ECFA remains a better option for promoting financial accountability in Christian ministries “than anything else that’s out there.”

He prefers voluntary accreditation, he said, rather than the government creating new “bureaucracies and administrations” to police religious groups’ finances, a possibility ECFA has lobbied against.

Strengthening its standards

In 2012, the ECFA created a special commission to look at financial accountability for religious groups. That commission was set up in response to a request for recommendations from Senator Charles Grassley, after he concluded a three-year investigation into alleged lavish spending by six prominent broadcast ministries in 2011.

The group issued a 91-page report that recommended more voluntary transparency by religious groups. It opposed the idea that churches and certain church-affiliated organizations should be required to file Form 990 information forms with the IRS, as tax-exempt organizations generally must do.

As a result of that report, ECFA in 2013 strengthened its standards concerning compensation and transactions, according to an article in Christianity Today’s Church Law & Tax.

“Moral compromise and financial mismanagement—only amplified in the media—have caused many people to lose trust in some of our nation’s most respected institutions, the church included,” said that article, co-written by Busby six years ago. “This in turn leads to additional barriers to carrying out the Great Commission.”

But now, the worry for Jones—the Village Church of Barrington pastor—is that ECFA accreditation itself could harm his congregation’s ability to fulfill its calling.

Christians who have left Harvest Bible Chapel make up roughly one-third of the membership at Jones’ church, which is affiliated with the Evangelical Free Church of America.

“It struck me that ECFA is little more than a rubber stamp. They’re relying on you to do an audit well, and as long as you’re ethical and upright, the seal means something,” Jones said. “I think they showed with the Harvest situation that you can cheat the system.

“So if that’s the case, if ECFA cannot catch that kind of thing, what’s the purpose of the seal?” he added.