In this series

A Southern Baptist Convention report on sexual abuse—released Saturday as the culmination of a year of study, listening sessions, and expert consultation—begins with the story of a woman who was sexually abused by her youth minister and pastor starting at age 14, at a church outside Birmingham, Alabama.

Susan Codone, one of more than a dozen survivors whose personal accounts appear in the report, calls herself “living proof that sexual abuse has been overlooked for many years in Southern Baptist churches” and declares the crisis “an epidemic powered by a culture of our own making.”

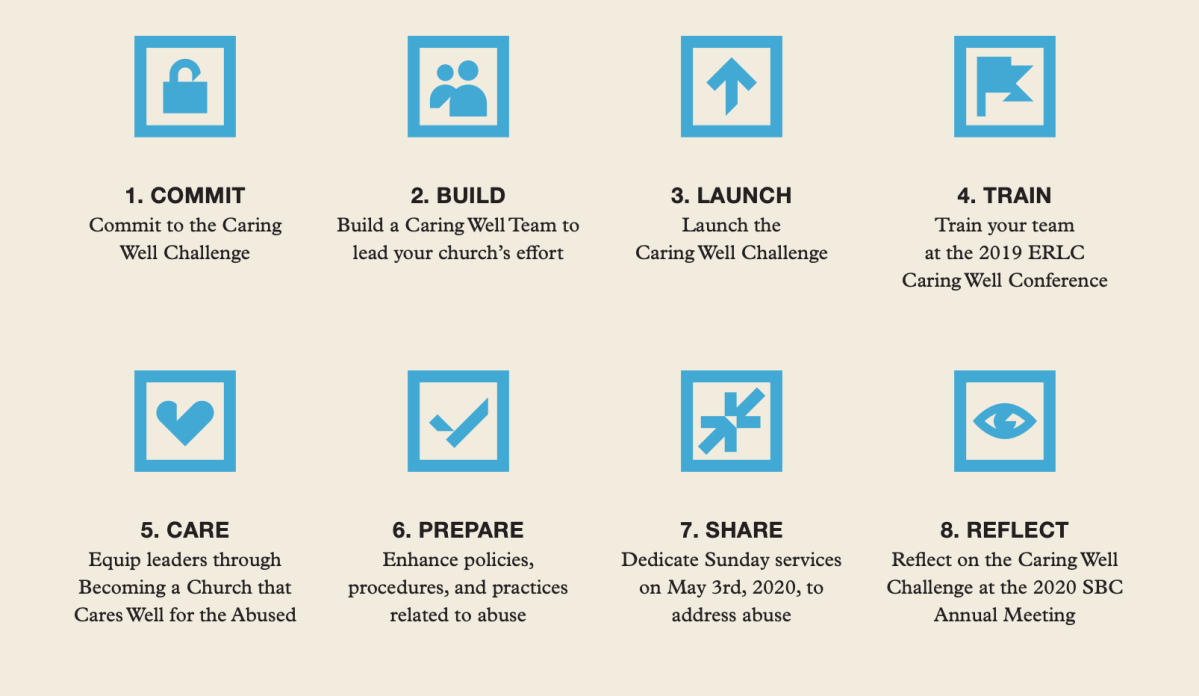

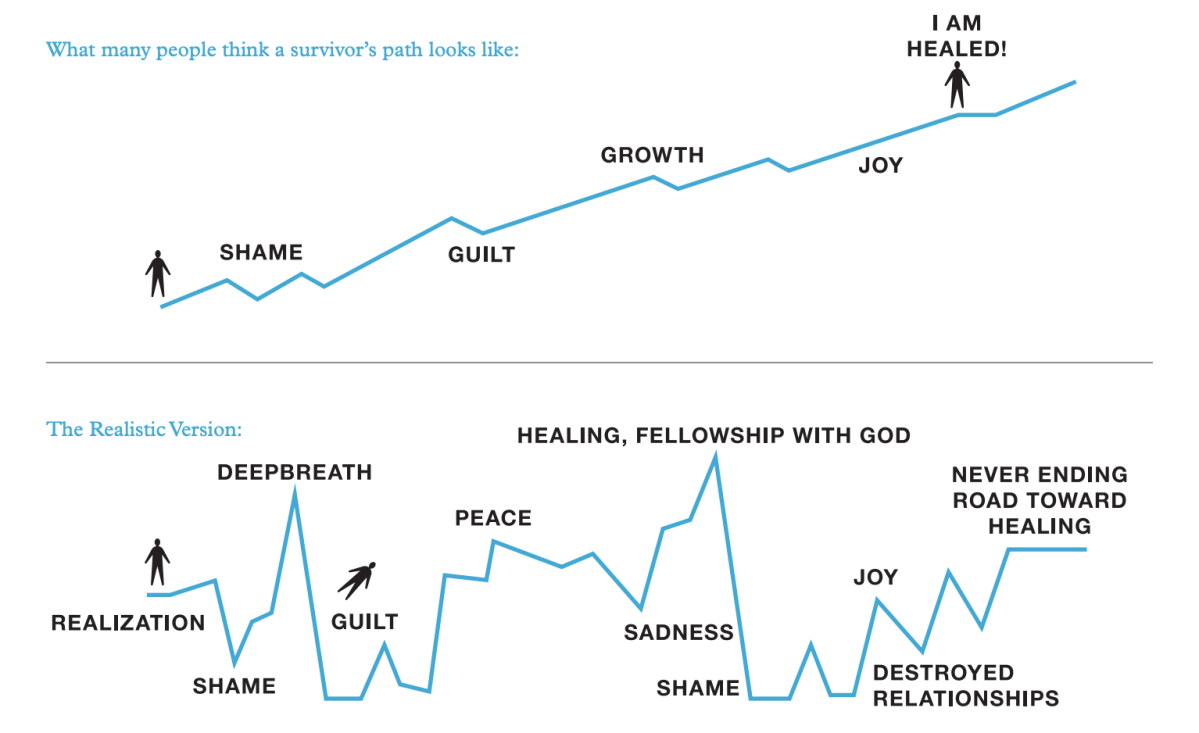

The 52-page document details the practical and theological failures of SBC churches and recommends a more rigorous response to prevent predatory behavior and “care well” for victims.

It is seen as a major first step to a denomination-wide movement around addressing abuse. What will come next depends, in part, on what happens in Birmingham this week, as thousands gather in Codone’s hometown for the convention’s annual meeting.

The issue of sexual abuse looms large, the subject of ancillary events, outside protests, and official business. The messengers are slated to vote on a proposed amendment to specifically name mishandling sexual abuse as grounds for disfellowshiping a church and may task a new committee to handle claims of misconduct by SBC churches.

President J. D. Greear commissioned the sexual abuse advisory group following his election last summer; the group was responsible for the recent report as well as a free curriculum for churches. He will present their findings officially on Wednesday.

The report’s tone reflects the kind of frank acknowledgement of the problem recently modeled by Greear and other top SBC leaders—including Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission president Russell Moore and Southern Baptist Theological Seminary president Albert Mohler—and incorporates directed critiques from survivors and advocates involved in the advisory group—including attorney-advocate Rachael Denhollander and abuse survivor and Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary alumna Megan Lively. (Both are profiled among the 10 women changing the SBC response to abuse featured in CT’s June issue.)

In one section, the authors state, “We recognize failures have occurred in many ways, including:

- Failing to adequately train our staff and volunteers—on the national, state, and congregational levels—to be aware of and respond appropriately to abuse

- Using church autonomy improperly to avoid taking appropriate action

- Failing to care well for survivors of abuse

- Failing to take disclosure seriously and to believe the survivor

- Failing to report abuse to civil authorities

- Recommending suspected perpetrators to new employment

- Promoting political, institutional, and congregational leaders whose language and behavior glorifies mistreatment of women and children.”

After a major Houston Chronicle investigation found credible abuse allegations against 380 SBC church leaders earlier this year, more from within the denomination began to push back against the common defense that because SBC churches are independent and autonomous, the convention could not address abuse among them.

The report owns the denomination’s position in repenting of its mistakes and building better systems to respond to abuse. North American Mission Board president Kevin Ezell stated that the SBC had “sometimes hid behind our autonomy,” but “we’ve waited way too long and the time is now to act.”

The advisory group’s report also goes deeper than previous statements on the subject; the report names “theological misapplications” seen as factors behind insufficient and harmful responses to abuse.

The list includes “wrong teaching that leads to treatment of women and children as inferior to men in value, intellect, and discernment” and “misapplication of complementarian teaching, leading to women submitting to headship of all men” as minimizing the sin of abuse, rushing to restore perpetrators, and suggesting victims might be to blame.

The report also condemns sexual relationships between pastors and members of their congregations as an abuse of power—a position written into law in the 13 states where clergy, like counselors, doctors, and other professionals, are barred from sleeping with their clients.

“Clergy abuse not only encompasses abuse to children, but also a ‘consensual’ adult sexual relationship between a clergy member and a congregant. The power and spiritual influence that a member of the clergy wields over their congregants essentially renders consent impossible,” the SBC report stated. “They often get the benefit of the doubt as spiritual leaders, can leverage their positions of power to manipulate others, can play the victim card if they are caught, and can spiritualize the situation to minimize personal responsibility.”

In sections on practical ways to improve abuse responses, the advisory group describes warning signs around people who may be grooming the church by pushing boundaries and recommends rules to minimize the risk of abuse: barring one-on-one settings in the church or transportation; requiring doors remain open; requiring volunteer screening beyond background checks; and avoiding sexual humor or innuendo.

The report follows a LifeWay survey on Protestants’ perceptions of abuse in church contexts; around a third believed there were “many more” abusive pastors yet to be found out. According to the survey, 10 percent of churchgoers under 35 and 5 percent of churchgoers overall had left a church because they felt sexual misconduct was not taken seriously.

The issue may be stirring involvement, concern, and prayer among younger Southern Baptists in particular. This is the second year in a row that women speaking out about abuse stand to shape the annual meeting; last year’s came just weeks after Paige Patterson’s resignation. Messenger attendance nearly doubled in 2018, with significant growth among first-time attendees and younger members.

“Though sexual abuse has rocked the SBC, I believe more progress has been made during the last 12 months in Christian transparency, gender equality, and Gospel fidelity than during the last 40 years combined,” tweeted Wade Burleson, a pastor and blogger who has critiqued aspects of the SBC for years, including Patterson’s leadership. “Brokenness brings repentance.”

Survivors have expressed disappointment that it took the #MeToo movement and attention from secular media for them to see significant momentum around reform in the SBC.

Over the weekend, many pastors and messengers headed to the annual meeting shared the new report on Twitter.

“This Caring Well report is tough reading,” wrote Malcolm Yarnell, theology professor at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary. “But the epidemic trauma caused by the evil of sexual abuse cannot be overcome through denial, ignorance, and changing the subject. Let us read, weep, become better informed, and change.”

The sexual abuse study group will continue to assess denominational responses as it enters the second year of a two-year, $250,000 project. According to an update posted earlier this year, the group will evaluate the possibility of a creating database of known predators, requiring background checks for SBC appointees, and adding survey questions on abuse incidents to the Annual Church Profile (ACP).

Churches can commit to implementing the strategies set forth in the report by signing up at CaringWell.com.