In this series

Update (January 8, 2021): The 4th US Circuit Court of Appeals on Friday sided with faith-based refugee resettlement groups that sued over an executive order allowing state and city governments to refuse refugee placements, affirming a lower court’s decision to block the order a year ago.

The appeals court agreed that the Trump administration policy “would cause inequitable treatment of refugees and undermine the very national consistency that the Refugee Act is designed to protect.” Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, Church World Service, and the Jewish organization HIAS also argued that the order would impede their scriptural calling to “welcome the stranger.”

World Relief, the humanitarian arm of the National Association of Evangelicals and one of nine nongovernmental organizations resettling refugees in the US, filed an amicus brief supporting the fellow faith groups.

Over the past four years, the refugee resettlement program dropped by 80 percent, down to a record low of 15,000 admittances a year. World Relief and other agencies are rallying for support as they anticipate a return to a refugee ceiling of 125,000 under President-elect Joe Biden.

—

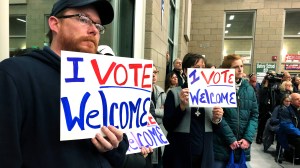

Faith groups are mobilizing in response to a new Trump administration policy that could prevent them from welcoming refugees and make it harder for refugees to reunite with family already in the US. Some refugee resettlement ministries are petitioning states, and others are suing the federal government as a December deadline looms.

President Donald Trump signed an executive order in September requiring state and local governments to opt in to refugee resettlement. Starting the day after Christmas, refugees will only be sent to areas where both the governor and a top county official have provided written letters to the administration saying refugees are welcome.

The additional layer of bureaucracy may mean that Christian ministries to refugees will not have more refugees to minister to. Resettlement groups may also be denied the funds necessary to help refugees adjust and build a life in America.

“This is a ministry that many churches have been a part of for decade,” said Matthew Soerens, director of church mobilization for World Relief. “We don’t want that ministry opportunity restricted.”

The new policy would likely impact the work of Brainerd Baptist Church in Chattanooga, Tennessee, according to senior pastor Micah Fries. His 2,000 member church currently hosts a Sunday night ministry for around 150 refugee newcomers, helping them with language acquisition, job skills, and other adjustments in their first six month in the US.

The ministry doesn’t end there, Fries said. The refugees often become part of the church community. If Tennessee Governor Bill Lee doesn’t send the administration a letter opting in to refugee resettlement, no new refugees will be sent to Brainerd Baptist Church.

“For us its not just theoretical, it’s practical,” Fries said. “These are friends of ours.”

New Rule Changes States’ Role

World Relief and Evangelical Immigration Table are circulating petitions to lobby governors and county officials to send the letters saying they will accept refugees before the deadline. It’s an effort to “get out ahead” of the policy, Soerens explained.

Refugee resettlement has always been done in cooperation with state and local governments. States could not block resettlement, however, or prohibit federal funds from going to counties, cities, or nonprofits that worked with refugees. The executive order changes that.

This could make a significant difference in states like Texas, where the state government has opposed refugee resettlement in the past and has an increasingly hostile relationship to some more liberal local governments.

Texas leads the country in refugee resettlement because of active programs in Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth, San Antonio, and Austin. Those cities have well-organized refugee welcome networks, and large immigrant populations where the refugees can find community and quickly become active and contributing members of the community. However, the cities’ desire to continue the program may hold no sway with Governor Greg Abbott, who has repeatedly reversed local policies and ordinances he sees as “socialistic.”

It’s likely that refugees will still find their way to those cities to be with family, according to Soerens, but there won’t be resettlement agencies to provide economic support, healthcare, and job training.

Refugees are in the country legally and can move wherever they want. However, refugee resettlement agencies like World Relief and Catholic Charities receive federal funds to support newcomers for six months while they find housing and jobs and enroll their children in local schools. If those services are not available in the cities where their families are, refugees have to pick between economic security and being with family.

There is a carve-out in the executive order for refugees resettling with spouses and minor children. Many, however, are trying to reconnect with extended family—adult siblings, grandparents, and cousins. These networks are often critical to building a sustainable life in a new country.

The World Relief and Evangelical Immigration Table petitions, focusing on 15 critical states, are circulating among pastors and lay people, Soerens said, many of whom feel their ministries would be weakened if refugees stopped coming to their communities.

Going to Court

Other refugee resettlement groups are asking the courts to stop the policy before it takes effect. HIAS (founded as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society), Church World Service, and Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service—have filed a joint lawsuit, the Religion News Service reported. The groups claim the excutive order violates the constitutional rules that govern refugee resettlement, which place the authority with the federal government exclusively, and not states and county governments.

The lawsuit outlines the effects of the policy as well: “The President’s order and resulting agency actions threaten to deprive thousands of refugees of their best chance to successfully build a new life and to burden thousands of US families who are waiting to reunite with their parents, children, and other relatives fleeing persecution. They threaten to deprive local communities that want to welcome refugees of the opportunity to do so. And they threaten to systematically dismantle the organizations—including Plaintiffs—that have spent decades developing networks, expertise, and resources to carry out the American ideal of welcoming refugees.”

Refugee resettlement has been a flashpoint before, when communities were concerned that terrorists would sneak into the country with Syrian refugees. However, Fries pointed out, refugees are thoroughly vetted, with the process taking years before they are brought into the US. Some critics also object to the six months assistance that refugees receive.

While people can debate the economic and security aspects of refugee resettlement, Fries sees the core of the issue as a moral one. For the church, he says, serving refugees should be a non-negotiable. He is determined to find a way to continue the church’s ministry no matter what bureaucratic obstacles are put in the way.

“I don’t really care what the government or anyone else says,” Fries said. “Our ultimate allegiance is to Christ and his kingdom.”