Millions of United Methodists have been waiting and wondering where their denomination will ultimately land in a decades-long dispute over gay marriage and clergy—and if a major split over the issue is imminent or if the debate will continue at its general conference once again next year.

Though the United Methodist Church (UMC) voted in February to keep its traditional marriage stance, barring congregations or conferences from performing same-sex ceremonies or ordaining gay clergy, whether that policy took effect in 2020 (in the US) depended on approval from the church’s Judicial Council, which released its decision this afternoon.

The council—a nine-member panel that essentially functions as the UMC’s Supreme Court—was tasked with reviewing the recently adopted legislation to ensure that it didn’t violate the denomination’s constitution, which contains guidelines about church structures and processes.

The Judicial Council’s ruling today was, as expected, a mixture of approval and rejection of the various pieces of the “Traditional Plan” at stake.

The top court rejected legislation that would have:

- added accountability for bishops who did not enforce the church’s rules;

- required denominational leaders to certify that they would abide by the rules;

- required a board of conduct “examination to ascertain whether an individual is a practicing homosexual.”

However, several of the petitions were ruled constitutional and will be enacted:

- a more detailed definition on what it means to be a “self-avowed, practicing homosexual”;

- added mandatory penalties for pastors who violate these rules;

- and tightened policy around the commissioning of bishops and church trials.

The court also approved legislation that provides a way for churches who disagree with the denomination’s stance on human sexuality to leave with their property. United Methodist News Service offers more analysis.

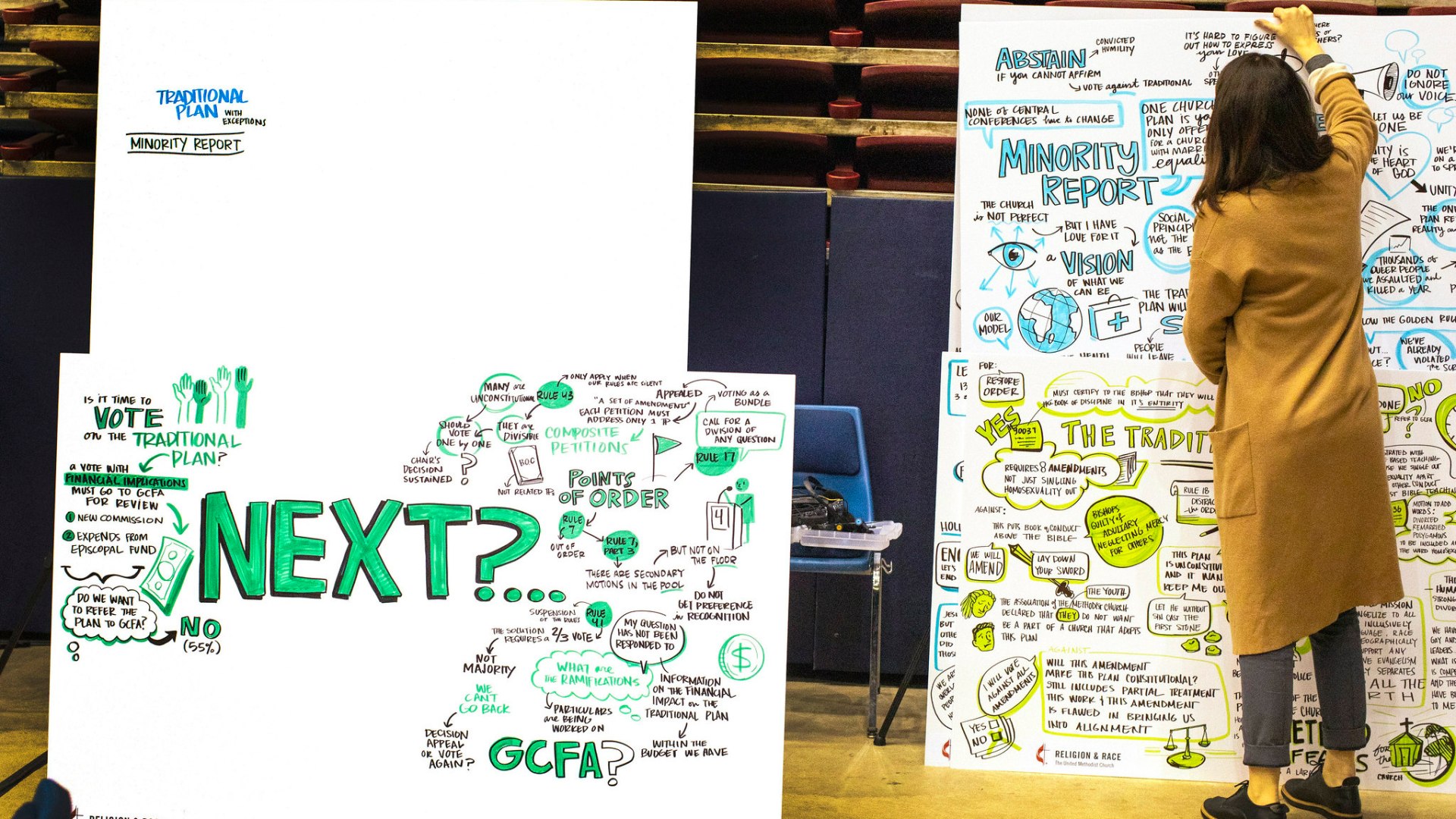

Earlier this year, UMC delegates had gathered for three days to try and chart a course through a 40-year-long minefield in the denomination’s position and policies over LGBT issues, particularly same-sex marriage and ordination. This special session of the UMC’s general conference ultimately voted in favor of the Traditional Plan, which reaffirmed its stance that homosexuality was “incompatible with Christian teaching” and strengthened its restrictions regarding marriage and ordination.

In the aftermath of the divisive denominational meeting, the Judicial Council had to rule on whether it was constitutional to strengthen accountability measures for pastors or churches that violate this stance. (In the US, certain churches and regional conferences have done so for years.)

They also considered the details of the “Gracious Exit” petition, which offered a pathway for congregations who would choose to not remain in the denomination to leave with their property and other resources. The Judicial Council must rule on what additional payments would be required to deal with outstanding pensions and other denominational obligations.

Because of time constraints at the earlier general conference, both the Traditional Plan and Gracious Exit petitions were passed before being amended to address constitutional problems the court had previously flagged.

Most Methodists expected the rulings to be a mixed bag—though it was possible that declaring certain provisions unconstitutional would dismantle the Traditional Plan overall. Since all the legislation was presented to the delegation together, the petitions could have been evaluated as a group rather than individually.

If that happened, the denomination’s teachings would have stayed the same, declaring that “the practice of homosexuality is incompatible with Christian teaching. Therefore self-avowed practicing homosexuals are not to be certified as candidates, ordained as ministers, or appointed to serve in The United Methodist Church,” and “Ceremonies that celebrate homosexual unions shall not be conducted by our ministers and shall not be conducted in our churches.”

But without the Judicial Council’s backing of the Traditional Plan, there would not have been additional provisions in place to hold entities accountable for violating these teachings or allow them a gracious exit (i.e., keeping their building) if they disagree and want to leave the UMC.

With certain elements of the Traditional Plan deemed unconstitutional, its supporters will be able to adjust the plan and pass the revised version again when the denomination convenes for its regular quadrennial meeting, which in 2020 will be held in Minneapolis.

Timothy Bruster, the Texas minister and delegate who made the motion for the Judicial Review, also has flagged language “singling out ‘the LGBTQ+ community’” as “contrary to the church’s constitution and violates the rule to ‘do no harm,’” United Methodist News Service reports.

It’s been two months since the denomination debated and voted at its special session, and American Methodists are still shaken by the outcome, which some characterized as “anti-LGBT.”

Progressive and centrist United Methodists in the US—who largely voted to change the denomination’s stance, while global delegates supported the traditional position—vowed to do everything from lobbying against the new rules to actively disobeying them.

Adam Hamilton, who pastors the denomination’s largest congregation—United Methodist Church of the Resurrection in Leawood, Kansas—faced a barrage of questions from fellow UMC leaders who felt like they were being pushed out of their own denomination. “They felt like this was not the church I signed up for,” he said. “It didn’t act this way. It wasn’t punitive. There was room for people to think differently.”

Most of the 13 official, UMC-affiliated seminaries have also pushed back against the Traditional Plan decision, citing concerns about the future of the UMC. “We are looking at losing a generation of leaders from our denomination,” Kah-Jin Jeffrey Kuan, president of Claremont School of Theology in Claremont, California, told United Methodist Insight. “Our students are telling us they are unsure whether or not this is the denomination they want to be a part of.”

Jay Rundell, president of Methodist Theological School in Ohio, told NPR, “We will resist what we see as a narrow misuse of scripture and tradition.”

The seminary that trains the largest number of newly ordained clergy each year, Asbury Theological Seminary, represents a more supportive exception. The school—which is not officially affiliated with the denomination and comes out of a broader Wesleyan heritage— stated that it was “thankful for the biblical stance the United Methodist General Conference has taken in recent days to affirm marriage between one man and one woman.”

Asbury president Timothy Tennent underscored that stance, writing, “The United Methodist Church is the only mainline denomination, to date, which has managed to maintain the biblical ethic on the definition of Christian marriage and the sanctity of our bodies as created ‘male’ or ‘female.’”

More conservative voices within the UMC maintain that churches can welcome LGBT members and uphold their value as image-bearers while holding a stance against same-sex marriage and gay clergy. “Even the most theologically traditionalist United Methodist congregations sincerely welcome all people, including our friends and loved ones who identify as members of the LGBTQ community, to come into our churches and participate in church life,” wrote John Lomperis, the United Methodist action director at the Institute for Religion and Democracy (IRD).

Though the Traditional Plan reaffirms the stance the denomination has held officially for decades, many in the nation’s largest mainline denomination say its passage puts them in a tough spot. Many US congregations have already taken a more open position, welcoming LGBT individuals and families into their communities and church leadership.

“Today if you tell people who are married, who have children, and who are gay and lesbian, ‘You are welcome here, but we just need you to know that your marriage is incompatible with Christian teaching,’ are you asking them to get divorced? Divide up the children?” Hamilton asked. “Saying we welcome everybody doesn’t sound welcoming when you’re still saying the practice of homosexuality is incompatible with Christian teaching.”

After the close of the conference, there has been a swell of resistance and support of LGBTQ advocacy organizations. Jan Lawrence, executive director of Reconciling Ministries Network, has been “overwhelmed by the individuals and churches reaching out.” Her network, which promotes full inclusion of the LGBT community, counts 1,018 churches and communities, totalling 41,000 Reconciling United Methodists.

Both sides of the debate seem to agree on two things. The first is that the conservative contingent among the 12.5 million-member denomination will have the upper hand if the Traditional Plan needs to be revised and voted on again.

Led by various factions within the UMC—including the Wesley Covenant Association (WCA), Good News, and the Confessing Movement—Traditional Plan supporters had the votes needed to pass the most conservative elements of the plan, and there is no indication that the votes will shift in favor of the centrists and progressives any time in the near future.

Second, they all agree that this issue now amounts to an insurmountable barrier. Mark Holland, executive director of the group Mainstream UMC, rallied for the One Church Plan, which would have allowed individual bodies and leaders to follow their conscience on same-sex marriage. Holland said the gathering “sent shudders through the US church” and that “the global governance structure of the UMC is irreparably broken” as a result.

The court’s rulings on the Traditional Plan and Gracious Exit measures were posted on its website after its meeting concluded today.