“Believing and belonging, without behaving.”

This is how the Pew Research Center summarizes the surge of Christianity in Europe around the fallen Iron Curtain roughly 25 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

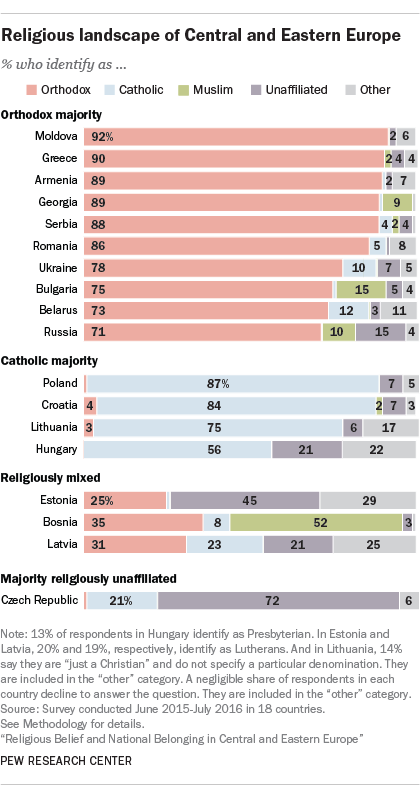

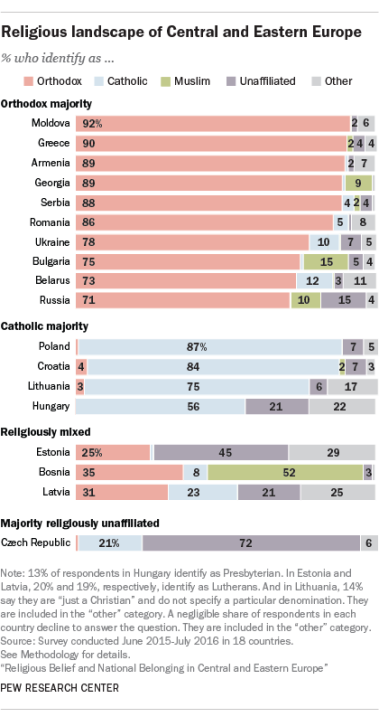

“The comeback of religion in a region once dominated by atheist regimes is striking,” states Pew in its latest report. Today, only 14 percent of the region’s population identify as atheists, agnostics, or “nones.” By comparison, 57 percent identify as Orthodox, and another 18 percent as Catholics.

In a massive study based on face-to-face interviews with 25,000 adults in 18 countries, Pew examined how national and religious identities have converged over the decades in Central and Eastern Europe. The result is one of the most thorough accountings of what Orthodox Christians (and their neighbors) believe and do.

Pew surveyed citizens in Armenia, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Georgia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, and Ukraine. (Pew did not survey citizens in Cyprus, Macedonia, Montenegro, Slovakia, or Slovenia.)

“Religion has reasserted itself as an important part of individual and national identity in many of the Central and Eastern European countries where communist regimes once repressed religious worship and promoted atheism,” Pew researchers stated. “Today, solid majorities of adults across much of the region say they believe in God, and most identify with a religion.”

While a minority in the region, Protestants are strongest in Estonia, where 20 percent identity as Lutheran; Latvia, where 19 percent identify as Lutheran; Hungary, where 13 percent identify as Presbyterian or Reformed; and in Lithuania, where 14 percent say they are “just a Christian.”

Only the Czech Republic remains majority religiously unaffiliated (72%), followed by a plurality in Estonia (45%), then Hungary and Latvia (21% each).

However, while citizens in once atheist countries are increasingly Orthodox, those in Catholic-majority countries are increasingly secular.

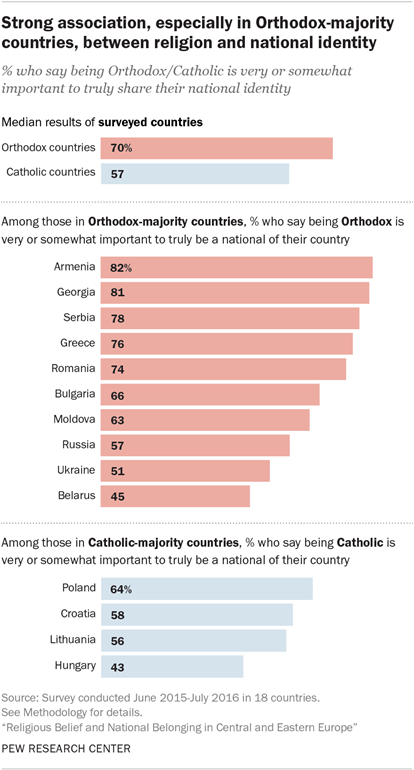

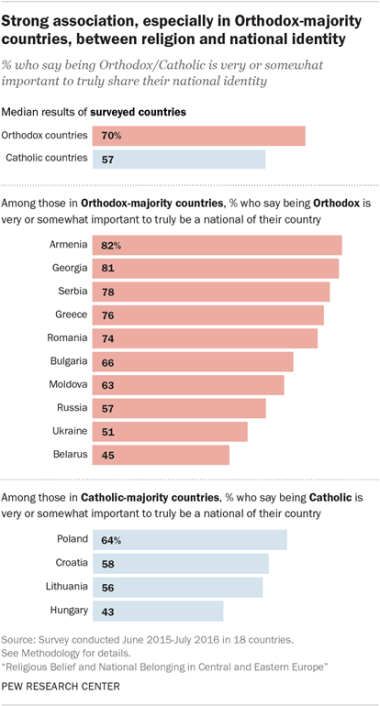

Across countries, solid majorities say that in order to belong, one must identify with the majority religion. For example, most say being Orthodox is essential to truly being Russian or Greek, while being Catholic is essential to truly being Polish. The close connection between religious and national identity is stronger for Orthodox than for Catholics (regional medians: 70% vs. 57%).

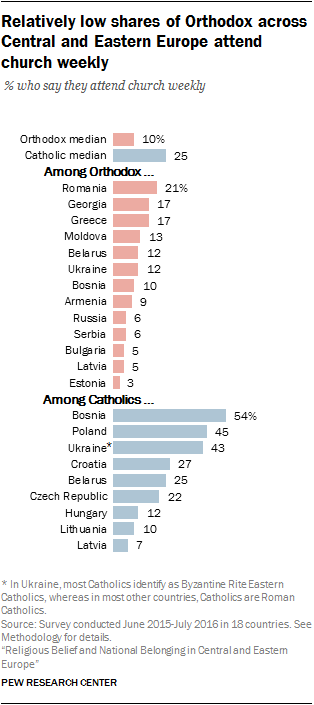

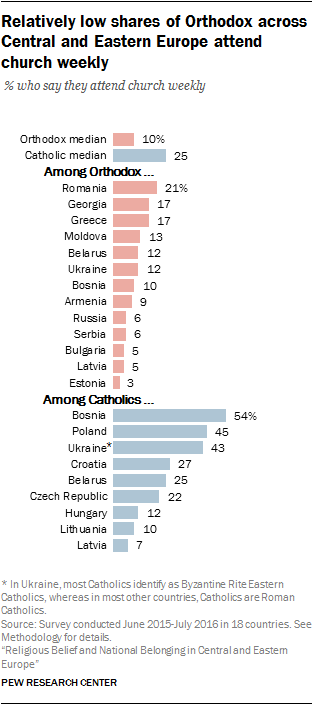

However, observance is a different matter. “Relatively few Orthodox or Catholic adults in Central and Eastern Europe say they regularly attend worship services, pray often, or consider religion central to their lives,” Pew researchers stated.

Catholics are twice as observant as Orthodox when it comes to weekly church attendance (medians: 25% vs. 10%). “In addition, Catholics in Central and Eastern Europe are much more likely than Orthodox Christians to say they engage in religious practices such as taking communion and fasting during Lent,” Pew researchers stated. “Catholics also are somewhat more likely than Orthodox Christians to say they frequently share their views on God with others, and to say they read or listen to scripture outside of religious services.”

Across the 18 countries, medians of 86 percent believe in God, 59 percent believe in heaven, and 54 percent believe in hell. Half also believe in fate, as well as the existence of the soul. Fewer than half pray daily.

Catholic-majority countries are more observant, but Orthodox-majority countries are more conservative on homosexuality and other social issues.

Citizens of Orthodox-majority countries are more likely than those in Catholic-majority countries to believe that their governments should fund national churches (medians: 56% vs. 41%) and promote religious values and beliefs (medians: 42% vs. 28%).

Surprisingly, this holds true regardless of church attendance. For example, in both Russia and Serbia, half of respondents favor state funding for the national church even though only 7 percent attend weekly.

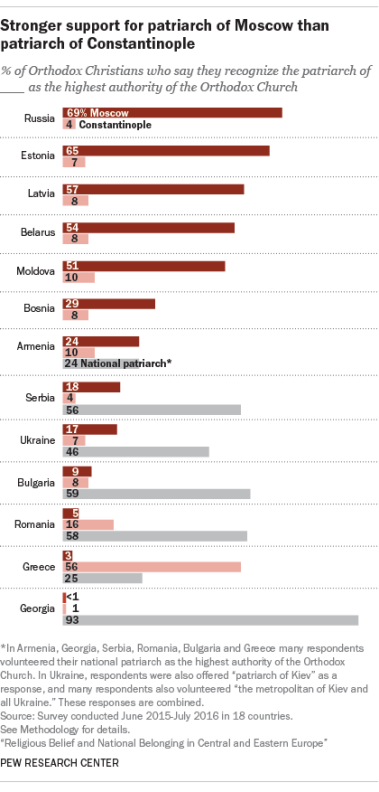

Pew also examined the deep regard for Russia, whose 100 million Orthodox believers make it Eastern Orthodoxy’s largest homeland by far.

Pew explained:

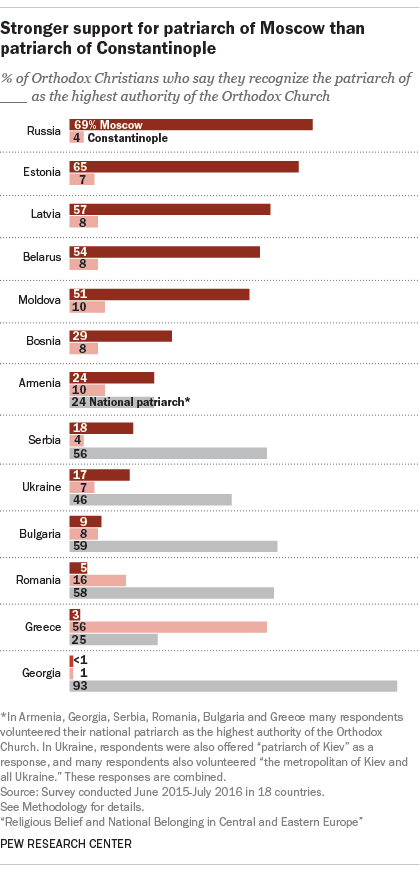

While there is no central authority in Orthodox Christianity akin to the pope in Catholicism, Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople is often referred to as the “first among equals” (in Latin, “primus inter pares”) in his spiritual leadership of the Greek Orthodox and other Orthodox Christians around the world.

But only in Greece did a majority of Orthodox Christians view the patriarch of Constantinople as Orthodoxy’s highest authority. Instead, “substantial shares” give that honor to the patriarch of Moscow.

Pew noted that this includes “roughly half or more not only in Estonia and Latvia, where roughly three-in-four Orthodox Christians self identify as ethnic Russians, but also in Belarus and Moldova, where the vast majority of Orthodox Christians do not self identify as ethnic Russians.”

Meanwhile, five countries had pluralities favor their own national patriarch. Armenia was evenly split.

Many also believe it is Russia’s duty to protect Orthodox Christians worldwide, both against terrorism as well as the West (and its liberal values).

In every majority-Orthodox country except Ukraine, most people agree that Russia has an “obligation to protect Orthodox Christians outside its borders.” Nearly 3 in 4 Russians agree.

However, Pew also found that “just 44 percent of Orthodox Christians in Russia say they feel a strong bond with other Orthodox Christians around the world, and 54 percent say they personally feel a special responsibility to support other Orthodox Christians.”

Pew summarized the differences in the “return of religion” to the region’s predominantly Orthodox and Catholic countries:

In the Orthodox countries, there has been an upsurge of religious identity, but levels of religious practice are comparatively low. And Orthodox identity is tightly bound up with national identity, feelings of pride and cultural superiority, support for linkages between national churches and governments, and views of Russia as a bulwark against the West.

Meanwhile, in such historically Catholic countries as Poland, Hungary, Lithuania and the Czech Republic, there has not been a marked rise in religious identification since the fall of the USSR; on the contrary, the share of adults in these countries who identify as Catholic has declined. But levels of church attendance and other measures of religious observance in the region’s Catholic-majority countries are generally higher than in their Orthodox neighbors (although still low in comparison with many other parts of the world).

The link between religious identity and national identity is present across the region but somewhat weaker in the Catholic-majority countries. And politically, the Catholic countries tend to look West rather than East: Far more people in Poland, Hungary, Lithuania and Croatia say it is in their country’s interest to work closely with the U.S. and other Western powers than take the position that a strong Russia is necessary to balance the West.

The survey, part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Future project, was conducted from June 2015 to July 2016.

CT’s previous reporting on Eastern Orthodoxy includes its humbled yet historic council in Crete and how Pope Francis and Patriarch Kirill made Christian history in Cuba.