In this series

While federal judges and lawyers argue over whether President Donald Trump’s revised executive order on travel amounts to a “Muslim ban,” evangelical experts on Muslim missions express concerns over how popular the proposal is in America’s pews.

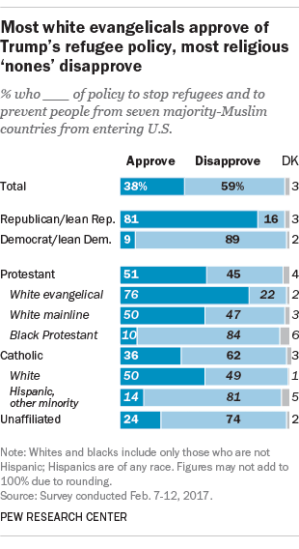

The Pew Research Center has found that self-identified white evangelicals were twice as likely as Americans overall to support the policy (76% vs. 38%), which temporarily halts the refugee program and restricts entry from several Muslim-majority countries. They are also, according to PRRI, the only religious group in America that has grown more supportive of a “Muslim ban.”

As Muslim migrants flee unstable and violent homelands, the mission field that was once half a world away is making its way to more and more American communities.

Last year, the United States admitted about 39,000 Muslim refugees, a record high.

“This is the best chance we’ve had in human history to share the love of Christ with Muslims,” according to David Cashin, intercultural studies professor at Columbia International University and an expert in Muslim-Christian relations.

But survey after survey indicates that white evangelicals are the least excited about their new neighbors. They show the highest levels of support for restrictions on Muslim immigration and the most skepticism toward Muslim Americans.

“Because of these attitudes,” Cashin said, “we could miss the opportunity.”

White evangelicals are also the least likely to know a Muslim, and their views often conflict with how Muslims in the US and abroad describe their beliefs.

“I think there is some fear on behalf of a lot of evangelicals,” said Michael Urton, associate director of the Coalition of Ministries to Muslims in North America (COMMA Network). “A lot of that is because people do not know Muslims. They do not know what Muslims believe, and they feel overwhelmed. It creates this paralysis.”

Muslims in the United States

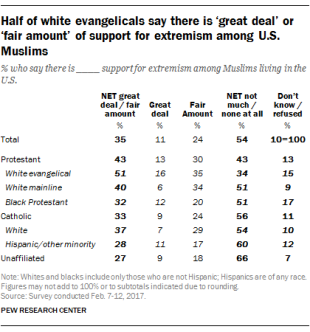

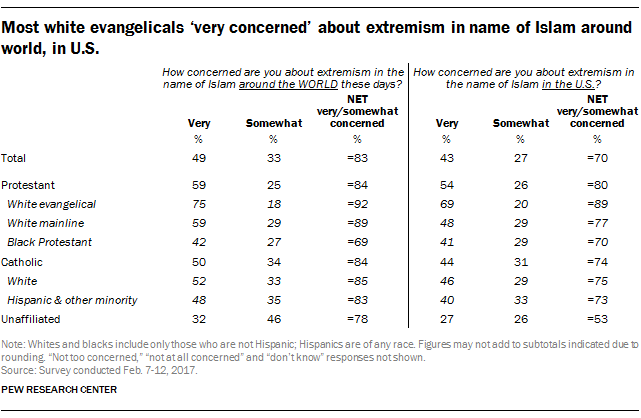

The majority of self-identified white evangelicals—about 70 percent—are “very concerned” about Islamic extremism in the United States, a recent Pew survey showed, compared to about 50 percent of Americans overall.

Half of white evangelicals also believe that there is a “great deal” or “fair amount” of support for extremism among Muslims living in the US. (This is a minority position among other faith groups.)

“We don’t want to be naïve and pretend that terrorism isn’t a problem, but we don’t want to be alarmist and assume that Muslims are all terrorists,” said Urton, whose Gurnee, Illinois, church hosted dozens of local Muslims at its Christmas service last year. “Many are victims of terrorism, and they don’t want to see their sons and daughters killed.”

Muslims now make up about 1 percent of the US population with an estimated 3.3 million people. White evangelicals, along with fellow Christians, remain concerned about how Muslim faith and culture fit with the American way of life, and doubt that immigrants and refugees can assimilate.

According to a PRRI poll conducted last year, 74 percent of white evangelicals, 66 percent of white mainline Protestants, and 63 percent of white Catholics said they saw Islamic and American values in conflict.

“That assumes that human beings can’t change, which is not a biblical value,” Cashin said. “If you want Muslims to assimilate, you better be out there showing them the love of Christ. If you want to reject them, they’ll form ghettos.”

Research from the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU) found that Muslims who indicate that their faith is important to them are more likely to emphasize their American identity as well. Muslims who are active in their practice are also more civically engaged; about half of regular mosque attendees have gotten involved with their neighborhoods and communities. No correlation was found between mosque attendance and extremism.

“Despite a too-common misconception of Muslim religiosity as at odds with an American identity, the two seem to go together; it correlates with civic engagement outside of the mosque as well,” Vox wrote. “Though mosques are sometimes portrayed as scary and alien—think of the protests against mosque construction in some areas in recent years—they are in fact harbingers of integration and engagement.”

While most American evangelicals worry about the application of Shari‘ah law in the US, according to a 2015 LifeWay Research poll, Muslims do not favor it. In the ISPU research, 55 percent opposed the use of Shari‘ah as a legal source, while 10 percent said it should play a role.

Though Muslim Americans are growing in number and prominence, a majority of white evangelicals do not know a single one. In a Pew survey released last month, just over a third (35%) say they have a personal connection to a Muslim, compared to about 40 percent of mainline Protestants and Catholics, 50 percent of unaffiliated Americans, and 73 percent of Jews.

The findings reflect broader divides between Christians and other faiths in North America. As CT reported earlier, 60 percent of adherents to non-Christian faiths do not have relationships with Christians. That means that most Muslims—as well as Hindus, Buddhists, and Jews—have no evangelical friends.

Bridging the divide takes more than symbolic gestures, wrote D. L. Mayfield, author of Assimilate or Go Home, who works with refugees and immigrants in Portland. “Have discussions about refugees (and Islam) with your people. Gently correct misinformation, every single time you see it. Be vigilant against hatred, specifically Islamophobia,” she advised her blog readers earlier this year. “Specifically ask Christians to live up to their beliefs when it comes to loving our neighbor (and our responsibility to them).”

Muslims Abroad

Americans are more worried about Islamic extremism internationally, with three-quarters of white evangelicals saying they’re “very concerned” about the impact of these views around the world, Pew wrote.

“It has to do with the fact that the evangelical church is in touch with Christian churches in the Muslim world. More than any other religious group, they’re hearing the horror stories,” said Cashin, the CIU professor, who has seen three of his friends and colleagues martyred as they attempted to bring the gospel to Muslim-majority nations. “For that reason, they tend to respond more negatively to the faith of Islam.”

Many associate the violent acts of ISIS extremists, who target Christians and other religious minorities, with Islam itself. In a LifeWay Research survey, slightly more than half of evangelical pastors saw ISIS as a true indication of what Islamic society looks like. They also disagreed with the notion that “true Islam creates a peaceful society.”

Warren Larson, former director of the Zwemer Center for Muslim Studies, called such beliefs “very damaging for ministry and mission among Muslims.” The survey statistics indicating Christians’ negative attitudes towards Muslims have played out in his experience among believers.

“The main cause seems most directly tied to 9/11 because during the five years following, quite a few evangelical books came out warning Christians to steer clear of Islam; in short, fear of Muslims grew substantially,” said Larson, who commented on such exposés in a 2006 issue of CT. “I felt such Christian writings often lacked solid research and were deficient in helping fellow believers reach out to Muslims with love and understanding.”

Yet, across Arab countries in the Middle East, researchers find most Muslims have relatively positive views towards those of other faiths.

“While state policies and the actions of extremist groups often mask the high levels of tolerance in the minds of ordinary Arabs, the typical citizen in this region expresses a great deal of support for tolerant policies,” said Michael Hoffman, who studied religious minorities as part of the Religious Freedom Project at Georgetown's Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. “Recent behavior by ISIS represents the opinions of a group of extremists rather than the Arab street.”

According to the Arab Barometer Survey, most Muslims across 10 countries said they’d be comfortable with neighbors of a different faith. In Egypt and Lebanon the support was nearly universal, and in Iraq—where Christians have been expelled by ISIS—82 percent of Muslims were comfortable with non-Muslim neighbors.

A strong majority of Muslims in Arab countries, even in Saudi Arabia, supported the right for religious minorities to practice their faith. More than 9 in 10 Iraqi Muslims agreed. “While knowledge about Christianity is low, tolerance of non-Muslims (Christian and otherwise) is high across the Arab world,” Hoffman said.

Majority-Muslim countries including Afghanistan, Iran, Turkey, and Yemen rank among the places where non-Christians have the fewest Christian contacts. African countries like Algeria and Somalia also make the list.

A 2010 Pew report on Islam and Christianity in Africa found:

- 43 percent of Christians on the continent saw Muslims as violent.

- 20 percent of Muslims saw Christians as violent.

- 60 percent of Christians supported making the Bible the official law of the land.

- 63 percent of Muslims supported making Shari‘ah the official law of the land.

“By their own reckoning, neither Christians nor Muslims in the region know very much about each other’s faith,” Pew said. “In most countries, fewer than half of Christians say they know either some or a great deal about Islam, and fewer than half of Muslims say they know either some or a great deal about Christianity.”

Mixed Messages

Though the polls reveal that white evangelicals are very concerned about Muslims’ impact on American security and values, many top US evangelical leaders are preaching a different message.

Last month, prominent pastors signed a letter along with 500 evangelical figures opposing Trump’s refugee ban, not just for the sake of persecuted Christians but also to assist “vulnerable Muslims.”

“Instead of cowering in fear over the imagined threat of an Islamic immigration invasion, the church can play the critical role in loving Muslim immigrants and helping them integrate into a very strange culture,” suggested evangelical writer Alan Noble.

The head of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, Russell Moore, has defended religious liberty for American Muslims.

“The United States government should fight, and fight hard, against radical Islamic jihadism,” he blogged last year. “But the government should not penalize law-abiding people, especially those who are American citizens, simply for holding their religious convictions, however consistent or inconsistent, true or false, those convictions are.”

Terrorism concerns have impacted Christian outreach to Muslims, as Fuller Theological Seminary professor J. Dudley Woodberry wrote for CT several years ago.

He concluded, “Ultimately, the future of missions to Muslims will be affected less by the flames of 9/11, or even the flames that started the Arab Spring, than by the inner flames that are ignited if we so follow our Lord, who modeled the basin and the towel, that our Muslim friends may echo the words of the disciples in Emmaus: ‘Were not our hearts burning within us while he talked with us on the road and opened the Scriptures to us?’”

Last December, two Muslim college students visited a nondenominational evangelical megachurch in the Rochester, New York, area as part of an assignment to learn about different faiths. The two young men stayed after the service to chat with the congregants. Some of them shared stories and offered hugs. One called Homeland Security.

The rogue report to the federal agency and state police ultimately made national news.

Though the case was an anomaly, it played into stereotypes of evangelicals’ unfamiliarity with Muslims and tendency to conflate Islam with terrorism. And the students’ reception at the church reflects the complicated relationship between white evangelicals and Muslims shown in the surveys and the news.

“Would a Muslim feel the American church is a safe place for them? The answer probably is they would not,” said Cashin. The more evangelicals come out in favor of Trump’s policies, he said, the more they exclusively view Islam as a threat rather than a ministry opportunity.

For Cashin, it’s both—and mission takes priority.

Islamic rule has led to unrest, violence, and spiritual hunger across the Middle East, and Christians should be willing to critique the ideology, he said. At the same time, that doesn’t make Muslims a danger to avoid, but a group for churches to open their doors with welcoming services, community dinners, and English classes.

“This is a moment Christian missionaries to the Muslim world have dreamed about for centuries.”