In this series

“So much of television is really not fit for children, or Christians, or the elderly,” declared Kenneth the NBC page, a character on the sitcom 30 Rock who pitched executives the idea of a black bar to block objectionable content.

Kenneth’s suggestion—a hit with the wholesome new network president in a 2011 episode—seems like an especially blunt caricature of faith-based filters compared to the real-life options available today.

But one of the most prominent services, VidAngel, had to suspend its streaming offerings last month as it faces a lawsuit from Disney and three other major studios. Yesterday, an appeals court rejected its request to keep streaming cleaned-up content while the suit unfolds.

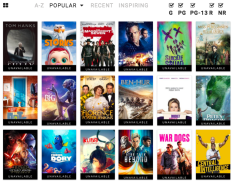

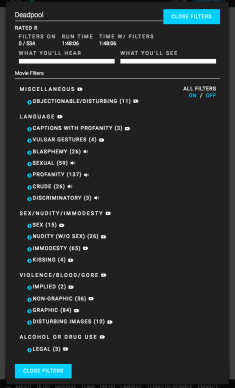

VidAngel lets viewers watch “however the bleep” they want, with hundreds of customizable filters to skip everything from sexual gestures and fight scenes to four-letter words and lighter offenses like butt. (The censor settings aren’t all “bosoms, blood, and bad words”; the company also lets you cut Jar Jar Binks scenes out of Star Wars.)

Its 100,000 customers are now back to watching movies the typical way: all or nothing. Last month, a preliminary injunction forced VidAngel to take down its 3,000-plus videos—everything from Game of Thrones to Minions—while fighting allegations from Disney, LucasFilm, 20th Century Fox, and Warner Brothers that the service violates copyright and encryption regulations.

VidAngel, founded by Mormon entrepreneur Neal Harmon and endorsed by leaders from evangelical groups such as Focus on the Family and the Family Research Council, follows a legacy of faith-based movie censorship that goes back as far as American cinema itself, according to film historian Michael Cornick.

Religious concerns over content prompted censorship boards and influenced the industry’s current rating system. Most of the dozen filtering services that came before VidAngel—such as CleanFlicks and MovieMask—had Christian or Mormon ties. And now, the results of VidAngel’s legal battle are expected to indicate the future of filtering in the digital age.

“The technology has changed so fast that the law has struggled to keep up,” said Cornick, a professor at Brigham Young University-Idaho. “The VidAngel lawsuit will likely determine how streaming will be affected with regard to filtering services in the long run.”

While several of its predecessors in the filtering business settled when faced with Hollywood lawsuits, VidAngel is ready to fight. The startup is surprisingly equipped for the case, with a former Oscars attorney as its legal counsel and $10 million in backer support.

VidAngel set crowdfunding records by raising half that amount in about a day, with more than 40,000 people overall contributing to their campaign to #SaveFiltering.

Harmon Brothers, the marketing firm run by Harmon and his three brothers and VidAngel cofounders, is a master at creating clever viral videos to promote VidAngel as they did for products such as Poo-Pourri and Squatty Potty.

Since the service was suspended after Christmas, even more customers have donated their account credits to the cause, said Harmon. Christians and Mormons come to VidAngel’s defense in comment sections to news stories covering the suit.

How It All Works

The structure of VidAngel is a little convoluted—as are the legal requirements around video filtering and streaming. Two major laws are at play: the Family Movie Act (FMA) of 2005 and the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DCMA) of 1998.

The first gives viewers the right to filter movies they own and watch in their own homes, provided they do not create a permanent censored copy.

To comply with this law, VidAngel purchases DVDs for the movies available on its site, then sells them to customers for $20 while providing a streaming version for them to watch on their computer, Apple TV, Roku, or other device with their designated filters in place. After they watch the movie or show, customers can sell the DVD back for $19—essentially making it a $1 movie rental. According to VidAngel, this assures that viewers own the movie and that no permanent censored copy is created.

However, the second law, which protects movie copyrights, bans people from decrypting DVDs, which VidAngel must do in order to stream a filtered version. (Legally, this switch in format is called “space shifting.”) The company argues that the FMA, as well as fair-use laws, exempt its decryption.

Paige Mills, media and entertainment attorney with Bass, Berry & Sims PLC in Nashville, told CT that VidAngel’s position is “pretty chancy” given the legal history:

The court’s opinion stated that there was no support for the position that space shifting is an allowed reason to circumvent encryption technology and sets forth that multiple courts have declined to adopt an exception for space shifting….

Senator Orrin Hatch, who introduced the FMA in the US Senate, explicitly stated that the FMA “does not provide any exemption from the anti-circumvention provisions of the DMCA.”

From VidAngel’s perspective, studios continually resist giving customers the option to censor objectionable content. They won’t authorize edited versions—like the ones that run on airplanes—and they shut down previous iterations of VidAngel’s business model, including a tool to censor already-purchased movies in YouTube or content licensed through Google Play.

“They contend that the filtering itself is a violation. They also contend that streaming is a violation,” said David Quinto, VidAngel’s lawyer. “It’s not a financial thing at all. If it were, the studios would offer to sell us a license.”

A victory for the Hollywood studios doesn’t leave VidAngel’s customers with many other options.

“If there is not a way for people to filter in the streaming age, then filtering will die in the DVD age,” said Harmon. “For us, that’s an unacceptable outcome.”

What Would Jesus Censor?

The counterargument to content filtering goes: If you don’t like a movie, don’t watch it—and don’t put money into the pockets of the people who made it.

But Quinto believes that people shouldn’t have to compromise their cultural relevancy in a country where pop culture is part of the unifying “common experience” just because they don’t want to hear another F-bomb. Watching a movie on your own parameters, in other words, is a way to be “in the world but not of it.”

Bob Waliszewski, director of Focus on the Family’s entertainment review site Plugged In, understands the decision to boycott explicit movies. He encourages viewers to ask themselves, “What would Jesus watch if he were here today?” Yet, he believes filtering lets Christians experience more of the box office’s best.

“There are movies that are inspiring, uplifting, and encouraging but they have just enough problematic content to keep them out of bounds for people who want to guard their hearts and minds in the body of Christ,” Waliszewski said. “We’re just a scene away…. We could walk out of the movie theater better people if we’re not tripped up by that nudity.”

VidAngel builds its brand mostly among a faith-based audience, the expansive subgroup that popularized recent blockbusters like the God’s Not Dead movies and War Room. Yet, instead of Hollywood settling on a more family-friendly middle ground at the movies, the industry has become polarized over the past decade, with Christian-centered storylines on one end and more explicit R-rated features on the other.

“For 2015-2016, there’s almost been a faith-based film a month that you could see in the theaters. That’s unheard of,” said Waliszewski. “On the other side of the pendulum, some of the worst of the worst has come out over the past few years.”

While evangelical standards can vary from household to household, Waliszewski lists sexual dialogue, sexual situations, nudity, vulgarity, and misuses of Jesus’ name among the most common concerns. The Mormon Church, Cornick notes, instructs youth to “have the courage to walk out of a movie, change your music, or turn off a computer, television, or mobile device if what you see or hear drives away the Spirit.”

Yet, it’s the seemingly family-friendly studios, including Disney, behind the suit.

“The common thread between those who are suing us is they are the movie studios that create more family-friendly content than the others,” said Harmon. “One complaint might be that VidAngel’s service makes a lot more content available to families, and perhaps that doesn’t make Mickey and friends very happy.”

Harmon believes VidAngel filters allow parents to be more engaged with their kids’ inevitable entertainment diet, not less. The parameters are not a “set it and forget it” license for his seven children to watch whatever they want; instead they talk as a family about why they chose to hide certain scenes. They also discuss why certain moviemakers raise artistic concerns about their doing so, he said.

What’s Next for VidAngel

The 50-person company had hoped to restore its video library later this month, but the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals denied its request for an emergency stay of the preliminary injunction order that forced VidAngel to suspend service last month.

“We are disappointed by [the] decision, but remain optimistic about our long-term prospects on appeal,” Harmon said in a statement. “Until our appeal is decided, we regret that VidAngel will not be able to offer filtered content. We continue to be grateful for the massive outpouring of support from across the country.”

As VidAngel assured fans on its website: “Remember that we have $10 million in the bank to continue this fight all the way to the Supreme Court. We are very optimistic that we will win the legal battle!”

This year, VidAngel will also begin populating the site with original content offered up by independent filmmakers (since Directors Guild members currently cannot license to them), as well as shows it produces on its own, like a series of family-friendly standup specials and a documentary about its lawsuit.

An earlier version of this article incorrectly identified Disney as the parent company of NBC.