In this series

Update (May 19): The United Methodist Church, under rising pressure from both sides to decide whether to allow same-sex marriage or non-celibate gay clergy, squeaked out of this year’s General Conference with a decision to punt the question to a committee.

By a vote of 428 to 405, delegates agreed to appoint a commission to study the issue. The church may call a special General Conference in 2018 or 2019 to address the results, Council of Bishops president Bruce Ough told delegates.

“We will coordinate this work with the various efforts already underway to develop global structures and a new General Book of Discipline for our church,” the proposal stated.

“We continue to hear from many people on the debate over sexuality that our current Discipline contains language which is contradictory, unnecessarily hurtful, and inadequate for the variety of local, regional and global contexts,” the proposal said. “We will name such a Commission to include persons from every region of our UMC, and will include representation from differing perspectives on the debate.”

LGBT supporters generally saw the vote as good news, even though it wasn’t clear how—or whether—infractions against the denomination’s ban on same-sex marriage and clergy in same-sex relationships will be disciplined in the meantime.

Conservatives were more cautious. Rob Renfroe, president of the evangelical Methodist movement Good News, stated that the commission is “fraught with peril” and cautioned that “well-known and respected leaders of the traditionalist and orthodox renewal movement” need to be included.

After rumors of a denominational split earlier in the week, the decision to wait effectively keeps the denomination together for a while longer, the Washington Post reported.

The UMC has voted to maintain the denomination’s ban on same-sex unions and non-celibate clergy for more than four decades, despite the movement of other mainline denominations to open the doors to the full participation of gay members.

—–

More than 850 Methodist delegates gathered in Portland, Oregon, were stuck.

With 100-plus proposals on what the United Methodist Church (UMC) should do about human sexuality—from deleting its Book of Discipline’s stance that homosexuality is “incompatible with Christian teaching” to allowing local churches to choose whether or not to approve same-sex unions and non-celibate gay clergy—organizers of the denomination’s quadrennial conference tried to develop a special process to address the issue.

Last week, delegates then spent three days debating Rule 44, which proposed that instead of having a committee of delegates compile and shape the proposals into a final petition, as per usual, the issue of sexuality should instead be considered by all 864 delegates—split into teams of no more than 15 people.

The small groups, meant to facilitate unity, would each report their petition recommendation to a six-person committee. In turn, that group would draft a final petition for all the delegates to vote on.

On Friday, delegates voted 355 to 477 against the proposal, in what is likely a preview of any vote taken on biblical sexuality. In general, Rule 44 was embraced by proponents of gay marriage and opposed by proponents of traditional marriage.

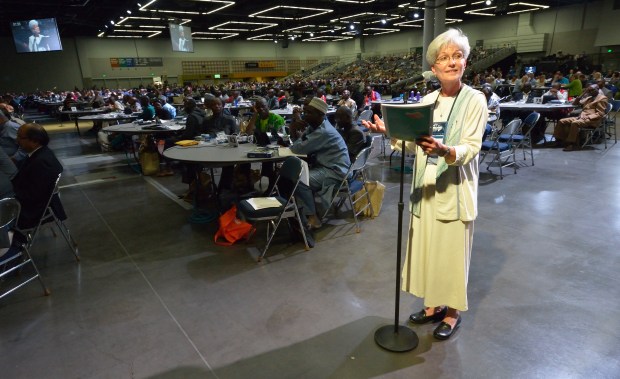

The Rev. Joy Barrett, a clergy delegate from the Detroit Conference, speaks on May 10 to the United Methodist General Conference in Portland, Ore. Barrett urged the conference to adopt Rule 44, which would move proposals regarding sexuality into small discussion groups designed to achieve consensus, as opposed to being voted on in a win-lose series of votes.

The Rev. Joy Barrett, a clergy delegate from the Detroit Conference, speaks on May 10 to the United Methodist General Conference in Portland, Ore. Barrett urged the conference to adopt Rule 44, which would move proposals regarding sexuality into small discussion groups designed to achieve consensus, as opposed to being voted on in a win-lose series of votes.

That’s probably because the usual method has been working pretty well for conservative Methodists who favor traditional marriage. Though other mainline denominations have opened the doors to the full participation of gay members, the UMC’s General Conference spent the last 44 years consistently voting to maintain the denomination’s ban on same-sex unions and on ordaining non-celibate clergy.

The UMC’s firm stance doesn’t stem primarily from its American members; less than half of them (46%) agree with the current ban, while 38 percent oppose it. Almost all of the 100-plus proposals on changes to the UMC's stance on human sexuality came from American conferences.

Some even spent the preceding weeks practicing denominational civil disobedience: the day before the conference began, 111 Methodist religious leaders revealed their homosexual orientation in an open letter. A week earlier, 15 clergy and candidates for clergy in the New York Annual Conference did the same thing. And elder David Meredith married his partner at a Methodist church in Columbus, Ohio, on the weekend between the two.

Photo by Kathleen Barry, United Methodist News Service

Photo by Kathleen Barry, United Methodist News ServiceSome US congregations and conferences have also gone their own way. More than 750 churches have joined the Reconciling Ministries Network, an organization that works for the “full participation of people of all sexual orientations and gender identities” within the UMC.

The Baltimore-Washington Annual Conference recommended a married lesbian for commissioning as a provisional deacon in February, noting that it was “not of one mind on the issue of ordination of LGBTQ individuals” with the denomination. In March, the New York Conference announced it would welcome candidates for ministry regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

But others are pushing back. The Eastern Pennsylvania Conference, which famously defrocked Frank Schaefer after he performed the marriage of his gay son, called on the General Conference to demand clergy accountability to the “rules of our common covenant” and to ask clergy to challenge the rules “through legitimate channels of holy conferencing, rather than breaking that covenant.” (Schaefer was later reinstated.)

The Alabama-West Florida Conference also passed resolutions in support of the denomination’s current stance.

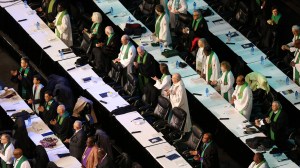

The conservative conferences have a powerful ally—the UMC’s African contingent. Of the 864 delegates attending the convention in Oregon, more than 40 percent came from outside the United States. Of those, three-quarters hail from Africa.

In November, more than a dozen African Methodist bishops representing 5 million members set precedent by speaking out publicly against homosexuality.

“We are deeply saddened that the Holy Bible, our primary authority for faith and the practice of Christian living, and our Book of Discipline are being grossly ignored by some members and leaders of our church in favor of social and cultural practices that have no scriptural basis for acceptance in Christian worship and conduct,” the African bishops stated. “The Christian marriage covenant is holy, sacred, and consecrated by God and is expressed in shared fidelity between one man and one woman for life.”

The voices of African leaders—which progressives have failed to sideline—will likely only get stronger: African Methodist churches are growing by more than 200,000 members annually. The Methodists on that continent are multiplying so quickly that some predict they will overtake the US members in five to eight years.

American Methodist churches have lost more than 52,000 members each year since 1974. In the 2013-2014 reporting year, the US conferences lost more than 116,000 members. Only 4 of the 56 conferences saw an increase in members, and only two managed an increase in worship attendance. (Even in the United States, theologically conservative Methodist churches are among the fastest-growing.)

In a denomination of more than 7 million, the loss may look small. But overseas, Methodists now number more than 5 million—with most in Africa. (In the United Kingdom, where Methodism was birthed, numbers dropped from 800,000 in 1906 to 600,000 in 1980 before dipping dramatically to 200,000 by 2015.)

In fact, a Methodist leader and economist warned US church leaders last year that they had only 15 years to turn around the decline before it would be impossible to do so. “By 2050, the connection will have collapsed,” Donald House Sr. told them.

While some of the loss can be traced to congregations that are leaving to protest the UMC’s soft stance on disciplining those who allow same-sex marriage and practicing gay clergy, a 2014 poll found that most Methodists (90%) don’t think issues of human sexuality are worth splitting over.

In fact, most (63%) said it was “diverting the church from more important things,” and, in a list of church priorities, ranked sexuality issues lower than creating disciples of Christ, spiritual growth, youth involvement, members’ spiritual growth, decline in membership, poverty, children at risk, and social injustice.

CT has reported on the UMC's attempt to sideline its churches outside America (which failed), and why some Methodist evangelicals have considered quitting while ahead. CT has also examined whether the UMC will schism over sexuality, and its debate on punishing pastors who break current rules.