In this series

The widely reported death by suffocation of Ding Cuimei, the wife of a pastor in China’s Henan province, has shocked Christians worldwide. Ding and her husband were buried as they attempted to prevent their church from being bulldozed by developers.

Ding’s husband managed to crawl to safety, but she did not. Their case highlights again the lack of legal protection for China’s Christians.

In Beijing, meanwhile, a less noticed but more significant event provides insight into how China’s atheistic regime plans to deal with the country’s growing Christian population, projected to become the world’s largest within the next couple decades.

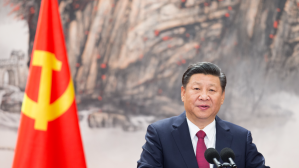

At a long-awaited national conference on religion, held April 22-23 in Beijing, China’s president Xi Jinping called on leaders to take the initiative in reasserting Communist Party of China (CPC) control over religion.

Xi’s speech, his first specifically on religion since coming to power in 2012, delineates a clear hierarchy in which religion is subordinate to state interests. According to Xi, uniting all believers under CPC leadership is necessary to preserve internal harmony while warding off hostile foreign forces that may use religion to destabilize the regime.

Xi’s insistence is not new, nor is it simply a function of China’s Communist rule. Since imperial times, state power has been seen as ultimate. It is, and has always been, the prerogative of the Chinese state to define orthodox belief and to set the boundaries for religious groups whose doctrines fall outside official limits.

In an environment in which the CPC is moving aggressively to rein in all expressions of civil society Xi’s message on religion comes as no surprise. His vision for reasserting control over religion—an area the CPC finds particularly difficult due to the diversity and complex history of China’s various religious communities—combines legal means with tightened supervision over religious doctrine and organizations.

Under the banner “rule by law,” Xi Jinping has overseen the drafting of new legislation and regulations governing nearly every sphere of life, from recreational dancing to national security. Curiously absent has been legislation dealing with religion.

In his recent speech, Xi made several references to regulating religion through law. Now that the first national conference on religion under Xi has been concluded, it is likely that a new law on religion is not far off.

For China’s Christians, such legislation could be a two-edged sword.

In the case of Ding Cuimei, police did arrest the perpetrators, and the local government has since ruled that the disputed piece of land does indeed belong to the church. In the future, local abuses such as this one and the well-publicized cross demolitions in the eastern city of Wenzhou could be effectively addressed by laws that put some teeth into China’s constitutional guarantee of religious freedom.

On the other hand, in the current atmosphere of social tightening, new laws could be used to further restrict the activities of Chinese believers.

The CPC’s control over religion is to be exerted not only through law, but also by reconciling religious doctrine with the party’s socialist values. While “religion serving socialism” has been in the CPC lexicon for some time, direct intervention in the beliefs and practices of individual religions—including calls for the “Sinification” of Christian theology—have become more common under Xi.

His speech directed religious groups to "dig deep into doctrines and canons that are in line with social harmony and progress … and interpret religious doctrines in a way that is conducive to modern China's progress and in line with our excellent traditional culture.”

Finally, Xi urged the cultivation of politically reliable religious leaders to head up the officially sanctioned religious bodies that are the interface between the CPC and the believing masses. Granted a certain degree of autonomy under current religious policy, these organizations nonetheless come under direct party supervision.

For China’s Protestant Christians, their designated place within the hierarchy is under the leadership of the Three Self Patriotic Movement (TSPM) and its sister organization, the China Christian Council.

Yet the majority of Chinese believers have chosen not to come under the TSPM umbrella. Many argue that the TSPM as a government-created political entity has no legitimate spiritual authority over China’s Christians. Other simply prefer the independence of being able to designate their own leaders and to organize and worship how and where they choose.

Up until now, this arrangement has proved workable, with most unregistered Christian groups agreeing to stay clear of politics while local officials tacitly agree to leave them alone as long as their gatherings do not become too large. Enjoying a measure of freedom within limits, these believers have become increasingly visible and socially engaged.

With the new emphasis on CPC supervision of religion, however, it becomes evident that there is no place for the majority of Chinese Christians within the prevailing hierarchy.

Choosing to make room for the believers who are currently functioning in this legal gray area would allow all of China’s Christians a legitimate role in contributing to their country’s future. On the other hand, should it exclude this growing and increasingly influential segment of China’s Christian community, the CPC will only succeed in alienating a significant proportion of those it seeks to unite.

Dr. Brent Fulton is president of ChinaSource and author of China’s Urban Christians: A Light that Cannot be Hidden (Pickwick Publications, 2015)