Since the early 1970s, the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) has stood in favor of the death penalty. It reasoned that capital punishment was an ethical stance for Christians because it works as a deterrent and lends appropriate gravitas to heinous crimes.

“If no crime is considered serious enough to warrant capital punishment, then the gravity of the most atrocious crime is diminished accordingly,” reads the NAE’s 1973 resolution. “We call upon Congress and state legislatures to enact legislation which will direct the death penalty for such horrendous crimes as premeditated murder, the killing of a police officer or guard, murder in connection with any other crime, hijacking, skyjacking, or kidnapping where persons are physically harmed in the process.”

Last week, the board of directors voted to update the NAE's stance, and acknowledge for the first time that opposition to the death penalty is also a legitimate application of Christian ethics.

“Evangelical Christians differ in their beliefs about capital punishment, often citing strong biblical and theological reasons either for the just character of the death penalty in extreme cases or for the sacredness of all life, including the lives of those who perpetrate serious crimes and yet have the potential for repentance and reformation,” the new resolution states. “We affirm the conscientious commitment of both streams of Christian ethical thought.” [Full text at bottom]

Founded in 1942, the NAE represents more than 45,000 churches from almost 40 different denominations.

“A growing number of evangelicals call for government resources to be shifted away from the death penalty," said president Leith Anderson. "Our statement allows for their advocacy, and for the advocacy of those of goodwill who support capital punishment in limited circumstances as a valid exercise of the state and as a deterrent to crime.”

In 2011, 76 percent of white evangelicals and 53 percent of black Protestants favored the death penalty for persons convicted of murder, according to data from the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI). In 2012, 62 percent of white evangelicals and 29 percent of black Protestants preferred the death penalty for those convicted of murder (the remainder preferred life in prison with no chance of parole). In 2014, 59 percent of white evangelicals, 25 percent of black Protestants, and 24 percent of Hispanic Protestants preferred the death penalty.

Overall, American opinion on the death penalty has remained fairly steady over the past 15 years; in fact, despite occasional swings, it looks much the same as it did in 1933, with about 60 percent in favor and about 40 percent opposed.

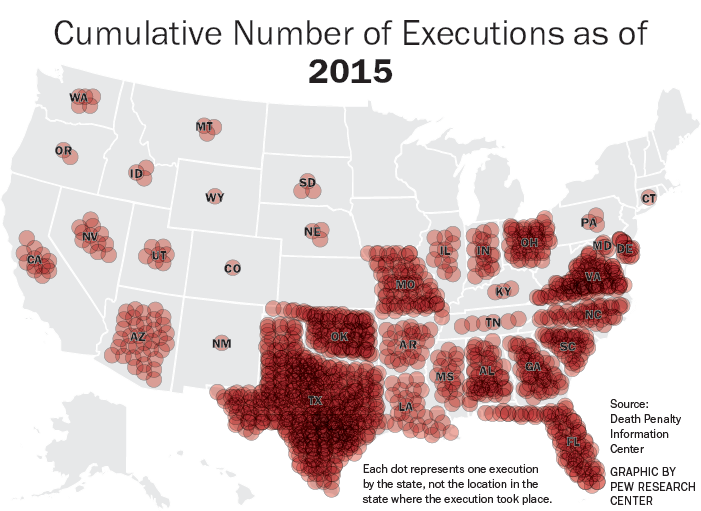

The Pew Research Center offers an interactive chart of state-by-state executions since 1977.

The NAE’s official change comes about seven months after the 3,000-strong National Latino Evangelical Coalition (NaLEC) voted in favor of capital punishment repeal, becoming the first evangelical association to formally take such a position.

“As Christ followers, we are called to work toward justice for all,” NaLEC leadership stated. “And as Latinos, we know too well that justice is not always even-handed. The death penalty is plagued by racial and economic disparities and risks executing an innocent person. Human beings are fallible and there is no room for fallibility in matters of life and death.”

Evangelicals have been prominent in public debates over the issue this summer, including the US Supreme Court’s ruling that Oklahoma’s method of lethal injection isn’t cruel and unusual and the banning of capital punishment in Nebraska. (The state became the 19th to abolish the death penalty.)

“As Christ taught throughout his ministry, no one is ever beyond redemption,” wrote a group of eight evangelicals, mostly pastors, who asked Nebraska to end the death penalty. “Yet the death penalty risks cutting short the process of redemption in the lives of those imprisoned.”

CT spoke out in favor of abolishing capital punishment after the execution of Karla Faye Tucker in 1998, arguing that the death penalty is unfair and discriminatory, that it doesn’t deter crime, and that it fails to console victims. CT spoke out again this past March, asking the state of Georgia to commute the death penalty of Kelly Gissendaner, a woman on Death Row.

Last month, Georgia executed the 47-year-old Gissendaner, who arranged for her husband’s murder but found faith in prison. She completed a theology program, became pen pals with famously jailed theologian Jürgen Moltmann, and garnered the support of 400 evangelical and Catholic leaders.

Correction: An earlier version of this blog incorrectly summarized PRRI data to show that evangelical support for the death penalty has "fallen over the past few years." The data cited asked different questions. When comparing the same questions over time, PRRI finds "no statistically significant shift" among white evangelicals from 2012 to 2014.

Here is the new NAE resolution:

NAE 2015 Statement on Capital Punishment

Evangelical Christians differ in their beliefs about capital punishment, often citing strong biblical and theological reasons either for the just character of the death penalty in extreme cases or for the sacredness of all life, including the lives of those who perpetrate serious crimes and yet have the potential for repentance and reformation. We affirm the conscientious commitment of both streams of Christian ethical thought.

We affirm with the Apostle Paul that governments are called to administer justice to protect citizens and preserve the common good. As citizens of the United States, we are grateful for the degree of public safety most Americans experience and the rules of due process embodied, if imperfectly implemented, in our legal system. American justice appears admirable when compared to that of many other countries where tyranny and corruption reign.

Unfortunately, all human systems are fallible. Nonpartisan studies of the death penalty have identified systemic problems in the United States. These include eyewitness error, coerced confessions, prosecutorial misconduct, racial disparities, incompetent counsel, inadequate instruction to juries, judges who override juries that do not vote for the death penalty, and improper sentencing of those who lack the mental capacity to understand their crime.

In the first decade of the 21st century, 258 wrongfully convicted people have been exonerated due to the introduction of DNA evidence. Twenty of those were serving time on death row, and another 16 had been convicted of a capital crime but not sentenced to death.

As evangelicals, we believe that moral revulsion or distaste for the death penalty is not a sufficient reason to oppose it. But leaders from various parts of the evangelical family have made a biblical and theological case either against the death penalty or against its continued use in a society where biblical standards of justice are difficult to reach. In Mosaic Law, standards of evidence were stringent, requiring a minimum of two eyewitnesses who were willing to stake their own lives on the truthfulness of their testimony and who would initiate the execution by “casting the first stone.” Circumstantial evidence was not permitted. The contemporary American system is unlikely to reach such standards of evidence, and given the utter seriousness of capital crimes, the alarming frequency of post-conviction exonerations leads to calls for radical reform.

Realizing the limitations of our system and the morally disastrous nature of any error, some jurisdictions have either abolished or placed a moratorium on the death penalty, choosing instead the sentence of life imprisonment without parole and bringing both executions and death sentences to a record low.

Near the end of the 20th century, some evangelical leaders began calling for a moratorium on the death penalty. Some have even argued that individuals who evidence repentance, conversion and amendment of life should have their death sentences commuted to life in prison. Their reasoning parallels the logic of Ezekiel 33: “I take no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but rather that they turn from their ways and live. … If someone who is wicked repents, that person’s former wickedness will not bring condemnation.”

Because of the fallibility of human systems, documented wrongful convictions, and our desire that God’s grace, Christian hope, and life in Christ be advanced, a growing number of evangelicals now call for government entities to shift their resources away from pursuing the death penalty and to opt for life in prison without parole as the ultimate sanction. They argue that such a move would allow time for the exoneration of the wrongfully convicted, avoid the tragic error of wrongful execution, and advance a higher sense of justice.

Other evangelicals continue to support the death penalty in limited circumstances as a legitimate exercise of the state’s responsibility to administer justice, and as a deterrent to crime. They point to heinous crimes, such as mass murder, terrorism, and the abduction, rape and murder of a young child, in which the perpetrator is caught on camera or is seen by multiple witnesses, where the evidence is overwhelming and there are no issues of mental incompetency. In such cases, some evangelicals argue for swift prosecution, with necessary safeguards, and if appropriate application of the death penalty as the best way to render justice, deter future crimes and allow the victim’s family and community to heal.

Despite differing views on capital punishment, evangelicals are united in calling for reform to our criminal justice system. Such reform should improve public safety, provide restitution to victims, rehabilitate and restore offenders, and eliminate racial and socio-economic inequities in law enforcement, prosecution and sentencing of defendants.