"Trust wholly in Christ; rely altogether on his sufferings; beware of seeking to be justified in any other way than by his righteousness."

John Wycliffe left quite an impression on the church: 43 years after his death, officials dug up his body, burned his remains, and threw the ashes into the river Swift. Still, they couldn't get rid of him. Wycliffe's teachings, though suppressed, continued to spread. As a later chronicler observed, "Thus the brook hath conveyed his ashes into Avon; Avon into Severn; Severn into the narrow seas; and they into the main ocean. And thus the ashes of Wycliffe are the emblem of his doctrine which now is dispersed the world over."

Timeline |

|

|

1302 |

Unam Sanctam proclaims papal supremacy |

|

1309 |

Papacy begins "Babylonian" exile in Avignon |

|

1321 |

Dante completes Divine Comedy |

|

1330 |

John Wycliffe born |

|

1384 |

John Wycliffe dies |

|

1415 |

Jan Hus burned at stake |

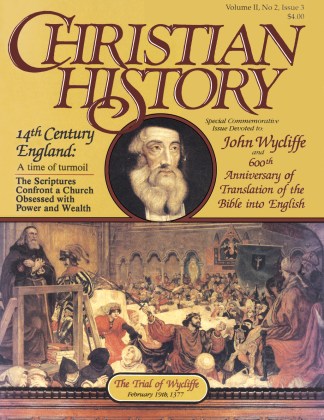

"Master of errors"

Wycliffe had been born in the hinterlands, on a sheep farm 200 miles from London. He left for Oxford University in 1346, but because of periodic eruptions of the Black Death, he was not able to earn his doctorate until 1372. Nonetheless, by then he was already considered Oxford's leading philosopher and theologian.

In 1374 he became rector of the parish in Lutterworth, but a year later he was disappointed to learn he was not granted a position at Lincoln nor the bishopric of Worcester—setbacks that some have seized upon as motives for his subsequent attacks on the papacy.

In the meantime, Rome had demanded financial support from England, a nation struggling to raise money to resist a possible French attack. Wycliffe advised his local lord, John of Gaunt, to tell Parliament not to comply. He argued that the church was already too wealthy and that Christ called his disciples to poverty, not wealth. If anyone should keep such taxes, it should be local English authorities.

Such opinions got Wycliffe into trouble, and he was brought to London to answer charges of heresy. The hearing had hardly gotten underway when recriminations on both sides filled the air. Soon they erupted into an open brawl, ending the meeting. Three months later, Pope Gregory XI issued five bulls (church edicts) against Wycliffe, in which Wycliffe was accused on 18 counts and was called "the master of errors."

At a subsequent hearing before the archbishop at Lambeth Palace, Wycliffe replied, "I am ready to defend my convictions even unto death…. I have followed the Sacred Scriptures and the holy doctors." He went on to say that the pope and the church were second in authority to Scripture.

This didn't sit well with Rome, but because of Wycliffe's popularity in England and a subsequent split in the papacy (the Great Schism of 1378, when rival popes were elected), Wycliffe was put under "house arrest" and left to pastor his Lutterworth parish.

Disputing the church

He deepened his study of Scripture and wrote more about his conflicts with official church teaching. He wrote against the doctrine of transubstantiation: "The bread while becoming by virtue of Christ's words the body of Christ does not cease to be bread."

He challenged indulgences: "It is plain to me that our prelates in granting indulgences do commonly blaspheme the wisdom of God."

He repudiated the confessional: "Private confession … was not ordered by Christ and was not used by the apostles."

He reiterated the biblical teaching on faith: "Trust wholly in Christ; rely altogether on his sufferings; beware of seeking to be justified in any other way than by his righteousness."

Believing that every Christian should have access to Scripture (only Latin translations were available at the time), he began translating the Bible into English, with the help of his good friend John Purvey.

The church bitterly opposed it: "By this translation, the Scriptures have become vulgar, and they are more available to lay, and even to women who can read, than they were to learned scholars, who have a high intelligence. So the pearl of the gospel is scattered and trodden underfoot by swine."

Wycliffe replied, "Englishmen learn Christ's law best in English. Moses heard God's law in his own tongue; so did Christ's apostles."

Wycliffe died before the translation was complete (and before authorities could convict him of heresy); his friend Purvey is considered responsible for the version of the "Wycliffe" Bible we have today. Though Wycliffe's followers (who came to be called "Lollards"—referring to the region of their original strength) were driven underground, they remained a persistent irritant to English Catholic authorities until the English Reformation made their views the norm.

Corresponding Issue