In this series

They were the most hated men and women in America. All across the South, rewards were posted for their lives. Southern postmasters routinely collected their pamphlets from the mail and burned them. In the North, these radicals were mobbed, shouted down, beaten up. Their houses were burned, and their printing presses were destroyed. For thirty years, to the very eve of the Civil War, the word “abolitionist” was an insult.

Why Are They Forgotten?

After the Civil War, abolitionists were lionized. Then, soon, they were forgotten. They still are.

Schoolchildren learn about Lincoln and how he freed the slaves, but the men and women who carried the slaves’ cause for thirty years (and who viewed Lincoln through most of his first term as an amoral politician) go nearly unremembered. People know mainly of the abolitionists’ underground railroad, which they regarded as a sideshow. Helping escaping slaves did nothing, they felt, to get to the root of the problem. Abolitionists wanted to destroy slavery root and branch, not pick up its fallen leaves.

One reason abolitionists are forgotten is that they were inescapably Christian in their motives, means, and vocabulary. Not that all abolitionists were orthodox Christians, though a large proportion were. But even those who had left the church drew on unmistakably Christian premises, especially on one crucial point: slavery was sin. Sin could not be solved by political compromise or sociological reform, abolitionists maintained. It required repentance; otherwise America would be punished by God. This unpopular message rankled an America that was pushing west, full of self-important virtue as God’s darling.

It remains an unpopular message today. Popular American history finds it much easier to assimilate Abraham Lincoln’s cautious, conscience-stricken path than to admire the abolitionists’ uncompromising indictment of their country’s sin. Yet without the abolitionists’ thirty years of preaching, slavery would never have become the issue Lincoln had to face.

Radical Demands in a Racist Society

Historians usually set the beginning of the abolitionist movement as 1830, because about then abolition’s principal figures—William Lloyd Garrison, Arthur and Lewis Tappan, and Theodore Weld—began their work. Long before, however, Americans had qualms about slavery. Before 1830 nearly everyone, slaveholders included, agreed that slavery should never exist in an ideal society

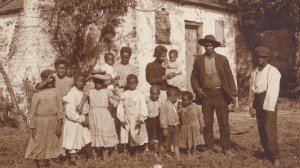

The problem was what to do about it. Slavery was important to the economy, both North and South. Americans North and South also profoundly feared freeing millions of slaves. Most Americans were frankly racist; they believed Africans to be not only inferior but also dangerous if not strictly controlled.

For some time, “colonization” had been the favored scheme of those who disliked slavery. Sending the slaves back to Africa would end slavery and eliminate the threat of African-Americans entirely. America would then be undefiled by an institution that contradicted its Declaration of Independence (“all men are created equal”), and untainted by an inferior race.

But abolitionists said an absolute no to colonization. Seen through the eyes of Christianity, colonization was immoral. What right did white Americans have to force black Americans to leave their native country?

Furthermore, abolitionists regarded colonization as a way of preserving slavery through a pretense of moral intentions. A few slaves might be shipped off to Africa, but the money and willpower to send all African-Americans would never come. Colonization was like a drunkard’s vow to quit drinking after just one more drink. William Lloyd Garrison, responding to a Congregationalist minister’s preference for a gradual elimination of slavery, asked whether the pastor urged his congregation to gradually eliminate sin from their lives.

Abolitionists called their program “immediatism.” To the consternation of their opponents—most Americans—they refused to discuss the problem of what to do with freed slaves. They regarded that as a fatal discursion. Their message was this: First repent of the sin, and then we can talk about what to do.

Not Force, “Moral Suasion”

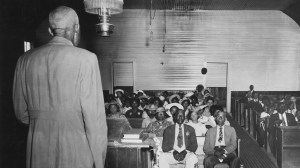

Quakers formed the core of abolitionism in the early days; they were the only large denomination to have officially banned slave holding. But the movement’s dynamism sprang from New England and the territories farther west, newly populated by Yankee farmers. In Boston and its surroundings, Unitarianism had recently all but supplanted traditional Christianity, but elsewhere Yankee Presbyterians and Congregationalists had taken up revivalism. In upstate New York, Charles Finney spurred huge revivals with thousands of converts. Finney preached that genuine conversion would always result in a changed life. Indeed, evangelicals formed a series of societies devoted to reform causes. The American Anti-Slavery Society, organized in 1833, was only one of these. It was, however, by far the most controversial.

Like all such societies, the American Anti-Slavery Society sought to change the world not by force but by “moral suasion.” In their official “Declaration of Sentiments” the founding delegates contrasted their methods with those of America’s revolution:

“Their principles led them to wage war against their oppressors, and to spill human blood like water, in order to be free. Ours forbid the doing of evil that good may come, and lead us to reject, and to entreat the oppressed to reject, the use of all carnal weapons for deliverance from bondage; relying solely upon those which are spiritual, and mighty through God to the pulling down of strongholds.

“Their measures were physical resistance—the marshalling in arms—the hostile array—the mortal encounter. Ours shall be such only as the opposition of moral purity to moral corruption—the destruction of error by the potency of truth—the overthrow of prejudice by the power of love—and the abolition of slavery by the spirit of repentance.”

Abolitionists repudiated government’s power in overthrowing slavery. They saw little value in a coerced repentance, even if it were possible. They believed, furthermore, that the U.S. Constitution gave the government no power to abolish slavery. (On this, later, many changed their minds.)

Garrison: Putting Power in Print

The problem was, abolitionists could not go south to speak to slaveholders about their sin. Abolitionists were in danger even as they formed their new organization in Philadelphia; farther south they would almost certainly be lynched.

Unable to go south personally, abolitionists hoped to send literature. Over thirty years, abolitionists published a huge number of newspapers, tracts, and books, particularly in the early years when Arthur and Lewis Tappan’s extremely successful New York business could fund the effort. But little of this literature reached the South, due to postal censorship.

Garrison’s paper, The Liberator, probably penetrated the South more than any other. It did so simply because southern newspapers could not resist quoting its long, vituperative passages to prove the abolitionists were fanatics.

The Liberator held influence far greater than its small circulation would suggest. Other newspapers came and went, but Garrison’s managed to infuriate and enthrall readers more or less continuously from 1831 until after the Civil War. For lonely abolitionists across a vast nation, The Liberator proved a constant stimulant. Garrison tended to condemn as a heretic anyone who disagreed with him, and to the distress of other abolitionists his intemperate style showed little imprint of the “power of love.” He was, however, unfailingly interesting.

Weld: Facing the Mobs

Garrison might have made few converts unless others had carried the abolitionist argument in person. Unable to reach the South, abolitionists held countless meetings in the North. They hoped a determined body of northern abolitionists would bring moral influence to bear on the South. Theodore Weld was the leading abolitionist in this mode. He was known as the “most mobbed man in America” because of the furious opposition he faced down in countless towns in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York.

Weld, converted in Charles Finney’s revivals, had become one of his chief lieutenants. Wherever Weld went he made a huge impact; every organization wanted a piece of him.

In 1832, while touring Ohio for a reform society, Weld was converted to immediate abolitionism. Shortly thereafter he converted virtually the entire student body of Lane Seminary, in Cincinnati; the students were expelled as a result. Weld then helped found Oberlin College, the first higher institution to admit both women and African-Americans, and moved most of the Lane students there.

Weld went on to become famous as an antislavery evangelist. His methods he learned from Finney’s revivals. Entering a small town or county seat for a series of meetings, he was usually met with rocks, tomatoes, threats, and sometimes, physical violence. Nevertheless, by the end of one to two weeks of nightly speeches or debates, Weld had nearly always silenced the opposition and converted a sizable part of the town to active abolitionism.

Battle for the Churches

Weld went on to train “The Seventy,” a group of abolitionist agents supported by the Tappans. The Seventy were sent out like Jesus’ disciples to imitate Weld’s success across the North. Weld, his voice damaged through constant overuse, retired from speaking but wrote two of the most important and widely distributed books of the abolitionist movement, The Bible Argument Against Slavery, and American Slavery As It Is.

In American Slavery As It Is Weld amassed clippings from southern newspapers and southerners’ testimony to show the cruelty of slavery. Northerners who had little personal knowledge of slavery were shocked.

Harriet Beecher Stowe, who had known Weld at Lane Seminary (her father, Lyman Beecher, was president when Weld was expelled), used American Slavery As It Is as her source and inspiration for Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The novel made an incalculable impact in creating anti-slavery sympathy when it was published in 1852.

In “The Bible Argument,” as it was called, Weld attempted to prove that slavery in the Bible was different in kind from American slavery, for Old Testament slaves had rights and were regarded as persons, while American slaves were property.

The argument was crucial for abolitionists. If southerners could prove that God accepted slavery, the claim that slavery was sin would dissolve. On the other hand, if abolitionists could demonstrate that the Bible condemned American slavery, rather than sanctioned it, they owned a powerful weapon in the battle to win the churches. Abolitionists expended great energy over this, believing that churches, linked North and South through their denominations, could bring an end to slavery. If slavery was sin, then churches would have to dis-fellowship slaveholders; and slaveholders, abolitionists hoped, would give up slavery sooner than they would give up their church.

Some churches accepted the abolitionist argument and did excommuncate slaveholders. More, however, felt that abolitionists were going too far. Abolitionists ended up disillusioned and disgusted by the church’s response, and some of them lost their faith. The churches, trying to keep peace at all costs, also failed: the largest denominations eventually split between North and South over slavery.

Finney: Foreseeing Blood

As time went on, abolitionist optimism withered. The rancor of the debate led Charles Finney, now president of thoroughly abolitionist Oberlin College, to urge Weld and his followers to pull back from abolitionism. Finney wrote in the summer of 1836, nearly twenty-five years before his words would be fulfilled:

“Br.[other] Weld, is it not true, at least do you not fear it is, that we are in our present course going fast into a civil war? Will not our present movements in abolition result in that? … How can we save our country and affect the speedy abolition of slavery? This is my answer.… If abolition can be made an appendage of a general revival of religion, all is well. I fear no other form of carrying this question will save our country or the liberty or soul of the slave.…

“Abolitionism has drunk up the spirit of some of the most efficient moral men and is fast doing so to the rest, and many of our abolition brethren seem satified with nothing less than this. This I have been trying to resist from the beginning as I have all along foreseen that should that take place, the church and world, ecclesiastical and state leaders, will become embroiled in one common infernal squabble that will roll a wave of blood over the land. The causes now operating are, in my view, as certain to lead to this result as a cause is to produce its effect, unless the publick mind can be engrossed with the subject of salvation and make abolition an appendage.”

Finney failed to convince Weld or any other prominent abolitionist. Like Old Testament prophets, they would tell the truth regardless of consequences. For them abolition had become God’s great cause on earth.

Success and Failure

Pure abolitionism lasted only through the 1830s. By the end of the decade, the movement was split into two factions. One, led by the cantankerous Garrison, centered in Boston. Many of its leaders had abandoned orthodox Christianity and added causes to anti-slavery: women’s rights, pacifism, “no human government” (which called for the end of any form of human hierarchy), and others. The other faction, led by the Tappans and other evangelical moderates, lost much of its potential when the economic collapse of 1837 bankrupted the Tappan brothers. Weld dropped out of abolition entirely in the early 1840s, due to a personal crisis in which he lost his faith and his hope for reform.

At any rate, the abolitionists’ success had overwhelmed them. They had begun numbering a few hundred; by 1840 they were thousands, organized into local anti-slavery societies across the North. The movement took on a momentum of its own.

Unable to reach southerners to plead for repentance, abolitionists began to petition Congress to abolish slavery where it had the power: in the District of Columbia, and in newly forming states like Texas or Kansas. A small cadre of abolitionist Congressmen brought slavery into political discourse, and slave-holding states fought back fiercely. The question could not be resolved politically any more than it had been religiously. Northerners became convinced that southerners would never be content until slavery dominated America. Southerners became convinced that they could accept no limitations on their property rights. In the end no middle ground remained.

Beginning in the 1840s, moderate abolitionists formed a new political party, the Liberty Party. This led to the Free Soil party, which led in turn to the Republican Party. Republicans, including Abraham Lincoln, were certainly not abolitionists. But they promised to limit the South’s power over the nation, and the millions that abolitionists had swayed supported them. Lincoln’s election led to southern secession, and secession led to war.

The wave of blood that Finney foresaw did indeed roll over the land, and slavery ended, not through repentance and love but through military coercion. By their original criteria of love and “moral suasion,” the abolitionists had failed. However, they thanked God when slavery ended, and most of them ultimately supported the Union Army and its Commander-in-Chief, Abraham Lincoln. They saw the war as God’s judgment and felt their thirty years of work had been vindicated, if tragically. They had stood for the truth, and faithfully offered Americans a possibility of cleansing from a terrible sin. The offer was refused, and God brought justice by other means: through the payment of blood, which freed the slaves.

Tim Stafford is senior writer for Christianity Today and author of numerous books including, with Dave Dravecky, Comeback (Zondervan, 1991). He is writing a historical novel on the abolitionist movement.

Copyright © 1992 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine.Click here for reprint information on Christian History.